Remembering Bernie Fedderly

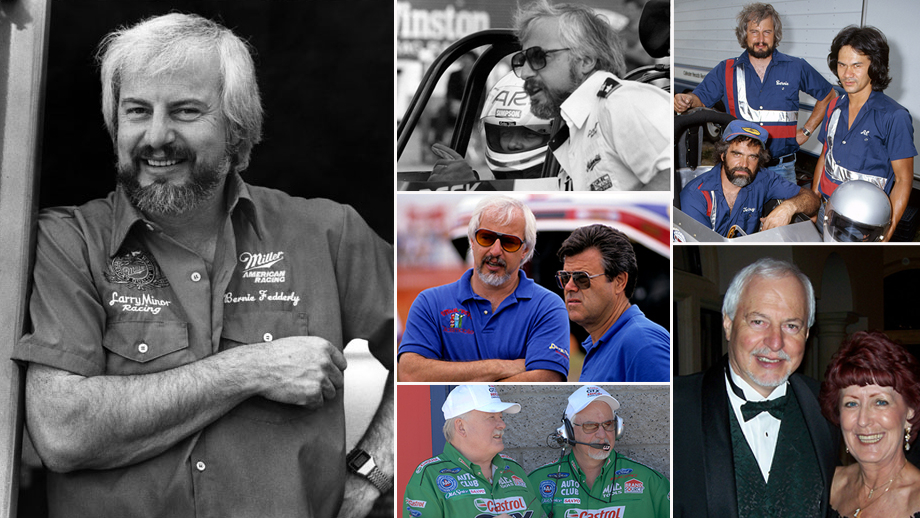

Henry Walther, a prominent member of the championship-winning Larry Minor Racing Top Fuel team of the 1980s, perhaps said it best: “If you can’t get along with Bernie Fedderly, you have a problem.”

Fedderly, Minor, Gary Beck, Ed McCulloch, Walther, Willie Wolter, Terry Caldwell, Dick Veenstra, and assorted others were part of what they jokingly called “the Hemet Mob” — Minor’s Southern California hometown and their base of operations — back in those killer 1980s when their Gary Beck-driven blue car ran rampant over the Top Fuel class, and they all knew what many before knew and many after would learn: Bernie Fedderly was a gentleman among gentlemen paired with an inquisitive mind and a desire to win.

I talked to a lot of people earlier this week — starting with Walther, Beck, and McCulloch, then on to Terry Capp, with whom Fedderly won the 1980 NHRA U.S. Nationals Top Fuel crown, then, of course, the guy with whom most of today’s fans most associate Fedderly — Austin Coil, who with Fedderly at his side since 1992 rode roughshod over the Funny Car class in tuning John Force to more than 100 wins and more than a dozen world championships — and, most sweetly, Bernie’s wife of 58 years, Mary.

They all told me what I already knew from more than 20 years of knowing the man, that he was a gentle giant whose presence not only made the world a better place but every driver that he tuned for became better and more successful.

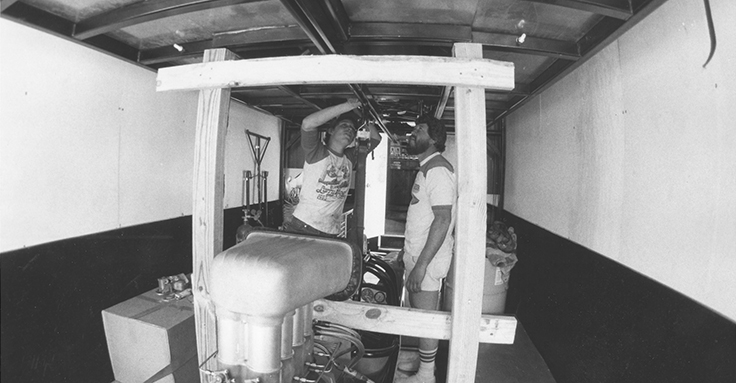

1982 was my first season with NHRA and also Fedderly’s first with the Minor team, but it wasn’t until 1984 when I embedded myself as a reporter with Top Alcohol Funny Car racer Jim DePasse’s team — which had a technical alliance with Minor — for a trip from Southern California to Florida for the NHRA Gatornationals, that I really got to know Bernie. Unlike today, when crew chiefs and drivers fly into the races while the crewmembers move the machinery down the road, the Minor team — drivers, crew chiefs, and crew — all traveled together in the tractor-trailer. The three days I spent on the road with those guys are forever etched in my brain for the camaraderie they shared.

I’ll never forget that the deck on which DePasse's flopper rode above Minor's dragster in the trailer had cracked and was threatening to turn Minor's digger into a pancake. Fedderly and a couple of the guys headed off searching for an open hardware store. Before long, we rendezvoused with them, and they bought some precut 2 by 4s and nails, which we pounded in with ball-peen hammers to create makeshift bracing. Ingenuity in action, as Wally Parks liked to say.

From Fedderly’s long career there through 1992 and into his long tenure with John Force Racing, he was a prince of a man, always greeting me at the trailer door and asking what I needed. While Coil was hunkered over the computer screen and sometimes unapproachable, Bernie was a wonderful liaison. He never said no.

But let’s hear from the people who knew him much better.

Terry Capp and Fedderly were buddies since St. Joseph Catholic High School in Edmonton in the early 1960s, decades before they made history in Indy. A lot of people think that Capp is some sort of one-hit wonder with that win because it’s the only one on his NHRA résumé, but the truth is they kicked ass for decades before that.

The two bonded over their love of cars — Fedderly had a ’36 Ford, and Capp and he worked on a ’32 Ford truck that became their first race car, which they raced on the No. 7 Supply Depot and around Calgary and Edmonton. Their success and the popularity of the blown gassers led them to build an injected Chevy-powered Anglia. Fedderly’s mechanical credentials were strong. He’d attended the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology and was a member of the Capitol City Hot Rod Association. His first professional steps were as a fleet mechanic before transitioning to drag racing with Capp.

“We thought maybe we could get into this drag racing thing a little deeper,” recalled Capp. “We were already out of school and working, so we had some money. We bought a ‘40 Willys coupe but changed our mind and bought a '49 Anglia, and that became the Capp-Fedderly Pioneer Shop Anglia.”

The boys raced hard and also played hard, according to Capp.

“Bernie was super easygoing, but I was kind of a badass guy when I was a little younger,” he recalled. “We had these local dances, and every once in a while, I’d pick a fight with somebody — y’know, just for something to do, like, ‘Come on outside’ — and Bernie would always come outside to look after me. He really wouldn't get mad until somebody poked him the wrong way, and he was big. I picked the fights, but Bernie finished them.”

After they exhausted all of the fun out of fighting and the Anglia, they set their sights on bigger things.

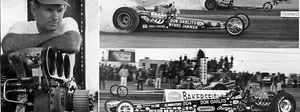

“We decided that we wanted a dragster because it looked like more fun and went through a couple of injected alcohol things that didn't quite work, but a friend had a front-motor 392 Top Fuel car, and we bought that in 1970, and that's how we kind of got into nitro racing,” he said.

Like everyone else, Capp, Fedderly, and partner Wes Van Duesen switched to a back-motored car in 1972 (with front-wheel pants) that got a 426 Hemi and, also like some of their Northwest peers like Jerry Ruth, also briefly had a Funny Car for match racing, both named Wheeler Dealer after Capp's auto parts business. At one race, they ran both cars but only had one engine and swapped back and forth, but that’s a story for another day that I’ll share.

So their Indy success in 1980 — where they qualified No. 2 and beat Johnny Davis, Ruth, Shirley Muldowney, Junior Kaiser, and, in the final, Jeb Allen — shouldn’t have been as big a surprise as it was except that few outside of the Northwest had ever really heard a lot about this Bernie Fedderly guy.

1980 Indy Top Fuel winners: Capp, Fedderly, and crewmember Al Mah.

One guy who had definitely heard of Bernie Fedderly was Gary Beck. Beck was part of the same Northwest Top Fuel world back in the 1970s, and when he moved from his native Seattle in 1969 to Edmonton to partner with Canadians Ken McLean and Bob Lawrence and marry his Canadian girlfriend Penny, he fell in with Capp and Fedderly.

“We met Bernie and his wife, Mary, and all of the Edmonton group of drag racers, and we became friends very early on,” Beck told me. “We were competitors against one another, but given the weather up there, you do a lot of socializing in the winter. Terry had the Wheeler Dealer speed shop, and we had a lot of sessions down there at night and after work, and you really got to know, you know, the guys in the fraternity there, and Bernie was certainly a major part of it, as was Rob Flynn, who was just a teenager working in that shop, sweeping the floor back in that day, and look at him now, and Bernie and Terry certainly mentored him.”

Beck had joined Larry Minor’s team in 1980 and a teammate with Larry Dixon Sr., and finished second in the championship race in 1980 and ’81. Looking for the missing piece of the recipe, Beck set his eyes on Fedderly, who had proven his skill with Capp in the previous decade.

“I will have to say I was a catalyst to get him to consider moving from Canada to the U.S. because we needed help,” Beck continued. “We had gone through a few people. Bernie at that time had a cylinder head business, but he was kind of looking for something else. It took quite a few months to convince him to give it a shot, and then he came to Minor’s mid-year in 1982, we were still running the pedal clutch but were transitioning into the centrifugal clutch, and Bernie had a lot of expertise in that. He came in, really helped us. If you look at the performance of our car, it started running really good in ‘82.”

At that year’s U.S. Nationals, Beck ran the first sub-5.5-second pass, a 5.48, and although they wouldn’t win a race together until the next spring, the die was clearly cast.

For his part, Capp was happy for his longtime friend.

“Beck's a smart man, and he was a great racer, and they made Bernie a hell of an offer,” said Capp. “Bernie realized he could be making some decent money, and I told him, ‘Do what you got to do. It makes sense, so by all means, go for it.’ ”

Beck was already a capable tuner of his own championship cars in the 1970s, and he and Fedderly bonded right away.

“I was deeply involved in fuel systems and was able to create good horsepower, but Bernie was great in the clutch department,” said Beck. “We’d spend a lot of time making moves with the fuel system, and initially, we smoked the tires a lot; we were able to get that under control. At the back end of ‘82 and into 83, we had nine straight No. 1 qualifiers in a row, and we started winning some races.”

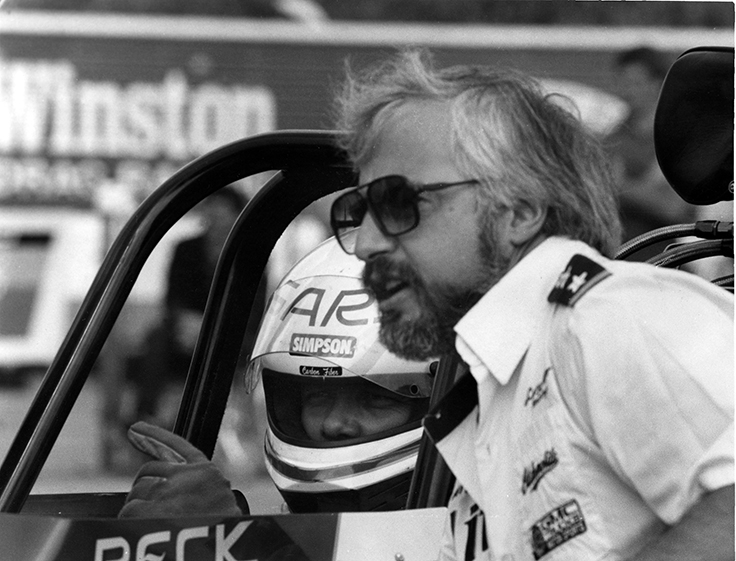

Beck and Fedderly won Atlanta, Indy, and Fremont in 1983, and the NHRA Golden Gate Nationals in Fremont in Northern California is where Beck and Fedderly made even more history with the first 5.3-second run, a 5.391 in the final round against Gary Ormsby (above), which they duplicated two weeks later at the NHRA World Finals at Orange County International Raceway, thanks to fuel-system genius Sid Waterman’s new high-flow “red” fuel pump.

With team owner Larry Minor in a second car, Larry Minor Racing ran 17 of the 18 quickest runs of 1983, Beck won the championship, and the team was named Car Craft Magazine’s Persons of the Year for 1983, but they also had been burning a lot of pistons in the process.

“Our engine needed more [fuel] volume, and we put it on our car before Fremont and Billy Meyer put one on his Funny Car, and the rest is history,” said Beck. “It came alive.”

Even under-driven by 6%, as it was, the red pump was capable of flowing a ridiculous [for the era] 20 gallons per minute, a big improvement over the 15 that racers were getting with overdriven Enderle 1200 pumps. Today’s fuel pumps crank out around 100 gpm, but the teams also have higher-power magnetos and two spark plugs per cylinder, which were not a thing yet back in the early 1980s.

“It also was a different era of racing because we were on the road together traveling, and you’ve got nothing to do but talk. Even when Bernie left the Top Fuel team to tune Ed McCulloch in Minor’s Funny Car [in 1986], we were still racing as a team and still talking because that was a big transition in that time period when the dual plugs and the more fuel pump and the data recorders were coming, and the crew chiefs were pressing hard, and there were a lot of good crew chiefs in the era like Dale Armstrong, Tim Richards, and Lee Beard. That was a big step forward for the sport through that time period.

“You couldn’t find a better-balanced person than Bernie, and he didn’t get mad very often, but he'd let you know if he wasn't happy. I remember us being in Columbus in 1983, and we were doing a lot of trick things with the fuel system — I had controls on the dash to change fuel pressure, for example — and Connie Kalitta wanted to see what we were doing. He was standing on the starting line as we're making a run, trying to look over the rear of the car, and Bernie kept shoving him away but, you know Connie, he keeps coming back, and finally, Bernie got him moved away a bit, and then he stood on his foot to keep him away so he couldn't see what was going on.”

Although Richards and team owner Joe Amato get a lot of credit for introducing the tall, laid-back rear wing engineered by IndyCar ace Eldon Rasmussen at the 1984 NHRA Gatornationals, Beck and Fedderly were also well down that road.

Recalled Beck, “We had been using IndyCar wings ourselves the previous year and had been working with Eldon because he was from Edmonton and was friends with my old partner Ray Peets, where they used to run sprint cars, which gave us an ‘in’ at Eldon's shop in Indy, but we never thought about putting it up high like Amato did.”

“Bernie had a great mind,” Walther added. “Bernie always had his eye on the ball of what we were trying to do, and he had a great thought process about how to go about different things, and he could weed out directions that we should go right. Larry Minor made some contributions to that success, as did Willie Wolter. It was a great team, and the success proves that out.

“I remember when we got the first data recorder on the car, and instead of having a graph, you could look at [it] to see where you're spinning the tires. It would print out like 10 sheets of numbers, maybe 500 numbers per page, and he’d go through that, and it confirmed the suspicion that we needed more traction, so we had to build some wider rims, and that was one more thing that helped out a lot.”

Fedderly ended up transitioning to the team Funny Car, which was driven by Funny Car legend Ed “the Ace” McCulloch. Word was that Fedderly had become disillusioned in some way with the Top Fuel effort and was ready to leave the team altogether, but McCulloch asked Minor to assign him to the Funny Car team instead. The Funny Car, first branded, like the dragsters with Miller Lite and then later Otter Pops, had not won in either 1984 or ’85, but Fedderly was the fix.

“Larry agreed to let Bernie come over, and we were off and running,” said McCulloch. “He was a dragster guy his whole life, but he was great with the Funny Car, and we worked hand in hand. I had always tuned my own cars, so he took over that and I did the clutch.

“This was when the [data recorders] were just coming into existence, and I used to laugh at Bernie because he’d take those toilet paper rolls of paper that used to come out on a bunch of dots and overlap two runs and hold them up to the light so he could see where they were different. He'd show me, ‘OK, you see right here, this is what we need to do, right here,’ but he was way ahead of me.”

McCulloch, who had driven and tuned his whole life by what he felt from his butt in the driver’s seat, was admittedly a little reluctant to accept the computer’s judgment.

“I mean, it was good data, but I told him we don't need that shit,” McCulloch said with a laugh. “We know what it's doing, right? Well, he was, once again, right.”

Echoing Beck’s earlier comment, McCulloch added, “We're in the [tow] vehicle hours on end, and you have a lot of time. You might just be driving down the road in a daze, and something will pop in your mind, and you throw it out there and you talk about it. We had lots and lots and lots of conversation going down the road, discussing, you know, what we should or shouldn't do. Bernie was great. I loved it when he came over to the Funny Car."

Although they never won a championship, McCulloch and Fedderly scored 12 wins, including Indy in 1988 and ’90 in the Miller High Life Olds. They were the first to break the 5.40-, 5.30-, and 5.20-second barriers and finished as high as second in the standings, in 1990 behind John Force, who won the title for the first time that year. It was also McCulloch and Fedderly in the other lane in Montreal in 1987 when Force finally won his first final round after nine runner-ups, with the Miller mount succumbing to a broken blower snout.

Fedderly ended up leaving the Minor team in early 1992, right after they signed the McDonald’s deal. McCulloch had gone back to his Top Fuel roots that year, while young Cruz Pedregon transitioned into the team’s Funny Car. Lee Beard was tuning for McCulloch and Fedderly was with Pedregon, but the Funny Car was not performing well. It was suggested to take Beard’s Top Fuel combination and put it in the Funny Car, which they did early in the year in Houston, and Pedregon won the race, and Larry decided they needed to keep that combination.

Recalled McCulloch, “Larry told Bernie, ‘This is what you got to do,’ and it was shortly thereafter, Bernie says, ‘I'm either going to do it the way I do it, or I'm out of here,’ and that's when they parted ways.”

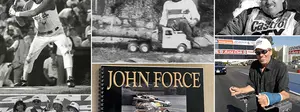

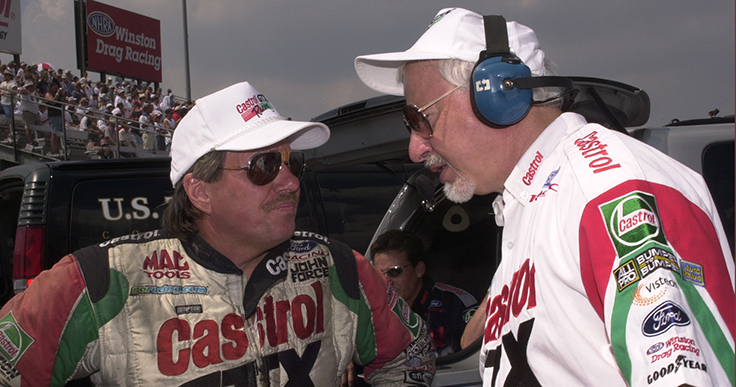

Fedderly didn’t stay unemployed long. Austin Coil was riding high after tuning John Force to back-to-back Funny Car championships in 1990 and ’91, and as his cars became more complex, he needed someone to help keep things in order.

“We were getting ready to go to Atlanta, and it was actually Force who suggested getting Bernie,” said Coil. “I only casually know the guy, and he said, ‘Well, let's hire him for a week and get a feel for if it's gonna be OK.' We hired him for the Atlanta race, and we won the race, so that was a really good sign.

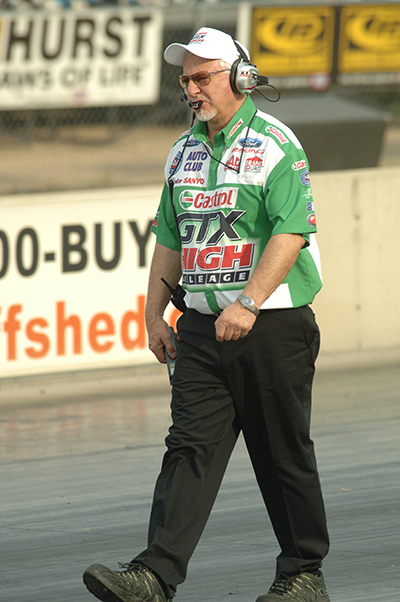

“I wasn't looking at it so much for an extra set of eyes as I was because there’s so many things you want to do between rounds and there really isn't time for me to oversee every one of them. You can't carefully adjust all the nozzles like you think they ought to be, and you sure don't want to overlook something else, and Bernie filled that gap.

“Bernie was always the best guy to read the racetrack. I can't walk on the racetrack for very long – I’ve had back troubles forever – so Bernie took care of the track walking, and we talked back and forth and made decisions, and it all worked out pretty good.”

And when it came to tuning input, the duo was always on the same page.

“There was only our way, and our way always seemed to be in agreement with one another,” said Coil. “And Bernie was a tremendously smooth mediator in helping keep the crew together. The crew guys are every bit as important as everyone else — it takes at least 10 guys working in unison with no mistakes to win a race, right? Any one of them can make you lose, and there's no one guy that can make up for all of that. It takes everybody to not make a single error, and Bernie was real good at keeping them in line without pissing them off enough to make them mad.”

When John Medlen was added as a third member of what Force called “the brain trust,” Coil took advantage and continued to experiment and pioneer everywhere from inside the bellhousing to the body’s aerodynamics, with assists on the latter from Tim Gibson and Johnny Stamper.

Fedderly was part of 109 national event wins and 13 NHRA Funny Car championships with John Force between 1992 and his retirement at the end 2012, including a record-breaking streak of 10 consecutive titles.

"It was never boring, that's for sure," Fedderly reflected with me in 2013 for this column about his career. "Force sometimes had a hundred ideas an hour, and it was up to us to make them happen, and sometimes that was pretty challenging, but we got through it. Some of the safety things that came from those times are important advances. Losing Eric [Medlen] and John's accidents [both in 2007] definitely were the down times; we went through some pretty low periods.

“Working for John Force was a really special and interesting time,” he said, probably understating the obvious. “We didn’t lack for anything. Force reinvested in the program, anything we needed, and it shows in the results. Force was never afraid to step up, and he wasn't afraid to try and gave all of us quite an education. He knew how to create chemistry and put the right people together.”

And when it comes to chemistry, that was the magic ingredient for Bernie and Mary Fedderly over more than 58 years of marriage, which began with a chance meeting at her house and ended with six decades of love, married when she was 20 and he was 23, the last few of which were a mixed bag of health for Bernie, including bouts with cancer and Parkinson’s disease. While she finds comfort in knowing he is no longer in pain, she admits that his absence leaves a deep void in her life.

“You know, you think you’re prepared,” she said, her voice tinged with emotion. “But you’re not. You really aren’t. You spend your whole life with someone, and then suddenly, they’re not there. It’s a strange, almost unreal feeling. But I know he’s not suffering anymore, and that gives me some peace.”

She reminisced about the early days of their marriage, particularly how Bernie and Capp would spend countless hours in the garage, working on cars and talking about racing.

“I remember thinking, ‘What is it about these cars that have such a hold on them?’ ” she laughed. “I didn’t get it at first, but I learned pretty quickly that if I wanted to be part of Bernie’s life, I had to accept that cars were going to be a big part of it too. And that was OK. It made him happy."

She recalled with a laugh one of her early trips to the race with him and Capp.

“I'd gone with them to Seattle, but back then guys really didn't want a bunch of women around,” she said. “While the guys were working on the car, I went down to watch a race, and when I came back, Bernie asked, ‘What happened to [whoever]?' And I said, ‘Oh, his fan belt broke,' and there was this dead silence. And of course, Bernie was mortified that his wife didn’t know it was the blower belt.”

One of the biggest turning points in their life together was their move to California. At first, the idea of relocating the family, including daughter Bernadette, seemed daunting, and Mary wasn’t entirely convinced it was the right decision.

“When he was offered the opportunity, I thought, ‘Well, we’ll go for a little while, and then we’ll come back home to Canada,’ ” she admitted. “But Bernie fell in love with it. And after a while, I realized — we’re not going back, are we?”

In hindsight, she believes it was one of the best decisions they ever made. The move opened doors for Bernie professionally, and though there were moments of uncertainty — such as when he left Minor’s team — she had faith that another opportunity would come along.

“I remember thinking, ‘What now?’ But Bernie wasn’t worried. He always had this way of staying positive, of believing something better was just around the corner. And sure enough, that’s when John Force came into the picture.”

Their life revolved around racing, and over time, Mary found herself traveling with Bernie more often, experiencing the world of NHRA firsthand, always to Reading in September for their anniversary and to the fall Las Vegas race for her birthday, and always Pomona. She saw how much Bernie loved his work and, more importantly, how much he was respected by his peers.

“He never cared about recognition,” she said. “He never bragged about what he had done. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame, and while he appreciated it, that wasn’t what mattered most to him. What mattered was that people he worked with respected him. That meant everything to Bernie.”

Even in his later years, as he battled Parkinson’s and then cancer, Bernie’s positivity never wavered.

“I think he, truly, honestly, was one of the most positive people I've ever even known," she said. “This man had a laundry list of problems between the Parkinson’s, the cancer had returned, we had scoliosis, and we had drop foot, it was just on and on and on.

“Every three months, they would do a Parkinson’s test on him and ask if he was OK, or was he depressed, and he’d say no, I'm looking at him going, 'Come on, Bernie.' And he'd say, ‘Mary, you know what? Do I like it, no, but do I not know that there's people with worse than I?’ If it was snowing, he’d say, ‘Well, there's a purpose for that.’ It's raining. ‘It's great.’ I could not make him sad, and so he made it very easy to even take care of him. He just told me, ‘I'm going to put one foot, if I can, in front of the other, Mary.’ He didn't want a burden, didn't want that to be part of the conversation. It was always, ‘I've got a few problems, but I'm fine,’ and I'm not just bragging him up because he's my husband. In the long run, I really was pretty lucky, because he really was a pretty good guy, and he was a terrific husband, and he was a terrific father. And my daughter, of course, is devastated. He was on the road, and I was with her all the time, and Dad would come in off the road and was her knight in shining armor.

“But when Bernie came in off the road, when he was home, he was home. There was no racing or whatever. He was never home for that long, but for a week or whatever, it was between races, but he was home, and when the season was over, he didn’t want to go spend time with the guys on a cruise, he wanted to be home with us.”

Now, as she navigates life without him, Mary takes comfort in the memories they shared and the impact Bernie had on so many lives, including hers.

“Bernadette and I were on either side of him when he took three last long breaths, and it was over,” she said. “He was as gracious in death as he was alive, because there was no anything. It was quiet, it was calm. His brow wasn't furrowed. There was nothing. And I thought, ‘You know, he did it for us,' but I did lean over and said to him, ‘I love you, and we're gonna be fine.' And I heard him [whisper] ‘I love you,’ no matter what effort that must have taken, and he did not suffer.”

Mary has been heartened to see so many wonderful comments on Facebook about her husband that has given her strength at this time. “There will be days I will grieve and I will shed tears, and I’ve shed a lot already, but what a wonderful life we had together.”

His old friends, like Capp and Graham Light were a constant in his life until the end.

“I’d go to a few national events and see him, and Force was always very accommodating," said Capp. "We’d hang out with them guys. The last time I saw Bernie was at Indy last year, but we talked at least once a week on the phone.

“Right before he passed, Mary — she's just an angel for what she went through — held the phone to his ear, and I started talking to him, and I could just hear him breathing. I wasn’t sure he was hearing me, but he and I had got a lot of Bernie-isms and Wes-isms and Terry-isms from hanging around so long. I don't remember which one I threw at him, but the heavy breathing stopped for a few seconds, and he actually tried to say something, so I knew he could hear me, and I was happy about that.”

Fellow Canadian Top Fuel racer and future NHRA Senior Vice President and Competition Director Light, pictured at right with his wife, Faye, and the Fedderlys, also was in that Edmonton-based group of Top Fuel racers in the 1970s, and he and his wife, Faye, often visited the Fedderlys after they moved to the Indianapolis area.

Light recalled, “I first met Bernie at a dragstrip in the early ‘60s. At that time, he was a mechanic working for a dairy company in Edmonton. On weekends, he tuned a gas Anglia driven by Terry Capp. Even though we were competitors on the dragstrip, he became a cherished friend. Bernie was a person of immense kindness, humor, and loyalty. In the 60-plus years of friendship, I don't recall him ever having a bad thing to say about anyone, he maintained his composure even in the heat of racing for a championship with Beck, McCulloch, or Force. He was one of the most likable people I've ever met.”

I don’t think we could agree more. Rest in peace, friend. Thanks for everything.

Phil Burgess can be reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE

Or try the Random Dragster Insider story generator