Ode to my best friend

I never had a biological brother, a familial sidekick to share life’s experiences, its ups and downs, its discoveries and surprises, its joys and its heartaches, another guy who was always there as your “ride or die” through thick and thin.

But I had the next best thing, a lifelong best friend who walked the same walk, talked the same talk, and melded his soul with mine from virtually the first time we met in our late teens. His name was Courtland Van Tune — just “Van” to his buddies and C. Van Tune to the world of motorsports journalism, where he was an icon and the most successful editor in the long and legendary history of Motor Trend magazine — and now he’s gone, stolen by that rat bastard known as cancer, at the still vibrant age of 66.

By its very definition, there’s one “best” of anything you want to count, and although I have lots of friends from inside and outside the drag racing community, there’s only one best, and for me, that was Van. And, as you'll read, without Van, I might not be writing this column.

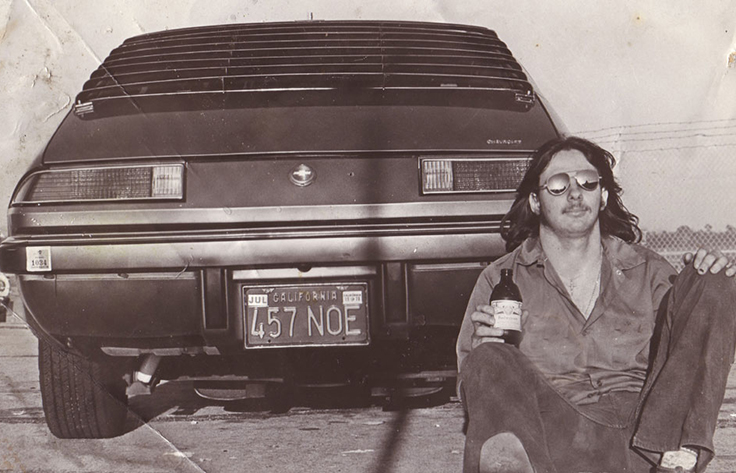

Van and I met because of the CB radio, the big 10-4 fad of the 1970s. We belonged to the same CB club and met at one of its functions and bonded almost instantly. Even though we lived just miles apart, we were in different school districts and likely would never have met. I was pretty rough and tumble in those days, all long hair and Schlitz Malt Liquor and ratty jeans as blue as the blue-collar life I grew up in. Van was much more refined, the only child of successful parents, a guy who would have fit in nicely at an Ivy League finishing school if not for his love of fast cars and penchant for leaving smoking tire tracks in his wake.

Somehow, against all odds, we became good friends, and Van became a second "son" to my mom.

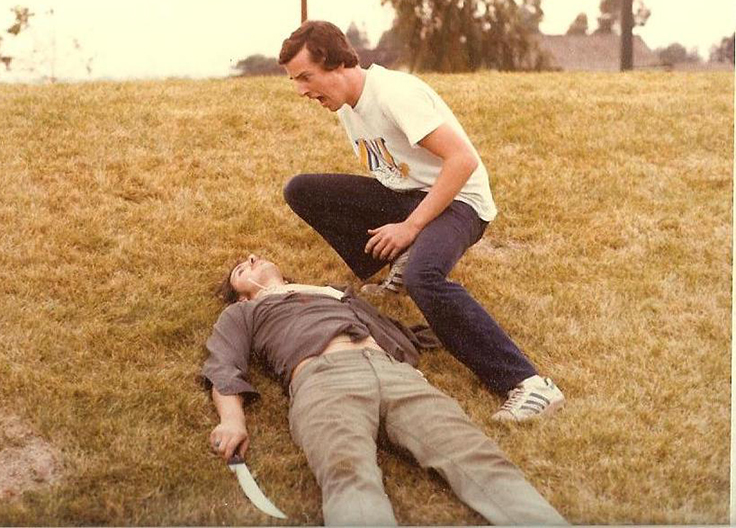

I mean, hey, just look at me, circa 1977. Would your parents let you hang out with me?

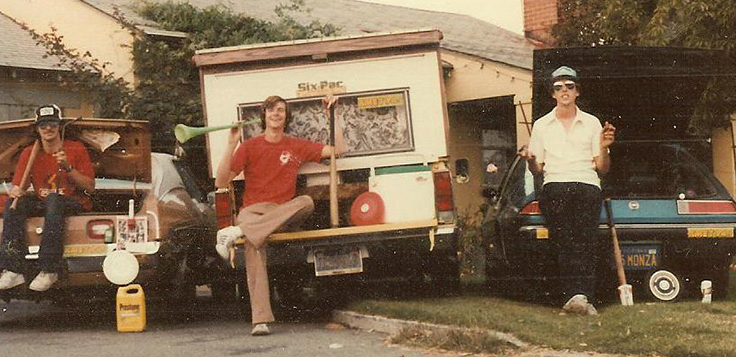

Van had a blue ’75 Chevy Monza, one of the few that came factory equipped with a 5.7-liter, 350-cid engine that was a blessing and curse. Chevy never should have shoehorned that engine into that little lightweight car because it ate front brakes and wheel bearings for breakfast, but, my oh my, was it quick. I had my parents’ hand-me-down ’74 AMC Javelin, and we both learned how to upgrade our cars, from B&M shift kits that performed the vital function of allowing you to “chirp” the tires on the 1-2 gear change to turbo mufflers and dual exhaust. On the CB, his “handle” was “Blue Streak” (because that’s what his Monza was), and I, of course, was “Drag Man,” having started my love affair with the sport years before.

We loved our cars and posed endlessly with them. Van's other lifetime friend, Mike Collins (center), was one of "the Boys."

We spent hours and hours and hours cruising around, looking for girls and street races – preferably the latter. Our Culver City home didn’t have much of a cruising scene, so we’d often venture to nearby Westchester, in the shadow of L.A. International Airport, where the Bob’s Big Boy had a strong reputation for fast cars and easy access to Pershing Drive, a two-mile stretch of no-traffic-lights straightaway that ran down the west side of LAX. We caught the scene at Van Nuys Boulevard not long before it dried up and tooled down Pacific Coast Highway to Hermosa Beach, which had a sweet and well-trafficked circular circuit. It was there, with Van riding shotgun, that I got my first ticket — “Speed Contest” — after laying down a tire-frying launch from a stop sign. I’d had my driver’s license for just seven months.

We took turns driving, depending on who had more gas in the tank, and it felt like we were out together almost every night. Like only guys can do, we could ride for hours and maybe utter only a word or two, vibing on whatever tunes we had on cassette — Jefferson Starship, Boston, Bob Seger, et al — and on the rumble of the exhaust beneath our seats. We even took our cars to Orange County International Raceway on one Wednesday “Grudge Night,” where he waxed me pretty good.

We developed our own lingo. The turbo mufflers were “Floyds,” taken from the plaid-jacketed Johnny Carson character “Floyd R. Turbo.” Police officers were “the bums” (apparently, we inherited this from another acquaintance). We both could quote chapter and verse from the script of American Graffiti, whose characters and lifestyles resonated with us (I always pictured myself as John Milner, Van as Steve Bolander; Van might argue the opposite), and some of those immortal lines were interwoven into our dialogue.

One of our most used was a goodbye, “Right-o. ‘Night” from the scene where Terry “the Toad” is outside of a liquor store trying to get someone to buy him some booze. He starts to ask the first guy he sees, a real straight-laced businessman type, and chickens out at the last moment and asks if he has the time (it’s quarter to 12).

While he waits for another accomplice, the businessman exits the store.

Terry: Hi. Still quarter to 12.

Man: Right-o. Night.

It’s such a perfect scene, and if you’re like me, you probably tried the same thing as a teen.

But now, all of those inside jokes and sayings will ring hollow to the world. It’s like being the last one alive to speak a language. I’ll be telling punch lines that no one gets. I’ll relive stories of our adventures to which I will be the only living witness.

Van and I had, to quote AG, “loads of fun” and more. I hate to brag, but we were living our best lives and getting as much out of it as we could.

His parents owned a small commercial building that was unoccupied and became our clubhouse. We’d work on our cars in there, talk on the CB, or just hang out with a growing collection of pals and take stupid photos like this one. We tuned up our CBs like we did our cars, adding extra frequencies and “linear amplifiers” to boost the signal. When the atmospheric conditions were right, we’d drive to the local mountains (there was even a place dubbed “Linear Hill,” and “shoot skip” on our radios, literally bouncing the signals off of the heavens so that a radio that should only have a transmission range of 25 miles could actually reach another state or even another country. It sounds a little geeky now because your cellphone does the same thing under any conditions, but it was heavy stuff back then.)

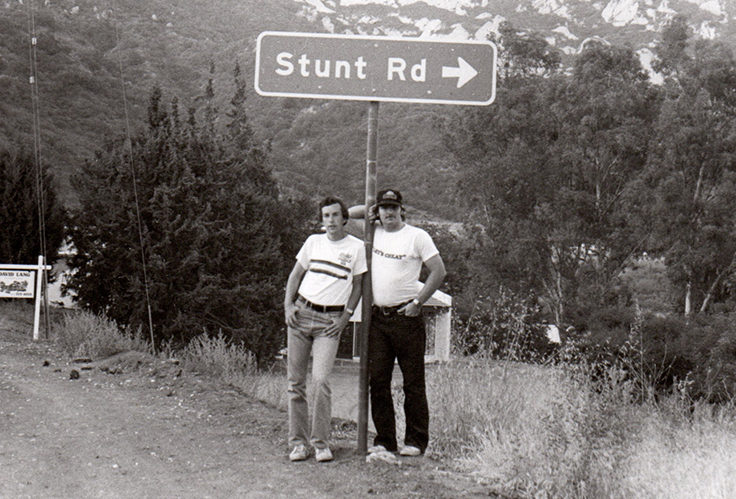

We did point-to-point timed car rallys together, carved our way perilously but perfectly down dark canyon roads, played Frisbee golf in deserted parking lots at 1 o’clock in the morning, and ate greasy Jack in the Box tacos. And we laughed. I can honestly say that in the nearly 50 years we knew each other, we never argued. Ever. I can’t remember a time when I was ever mad at him or him at me. Damn, it was good.

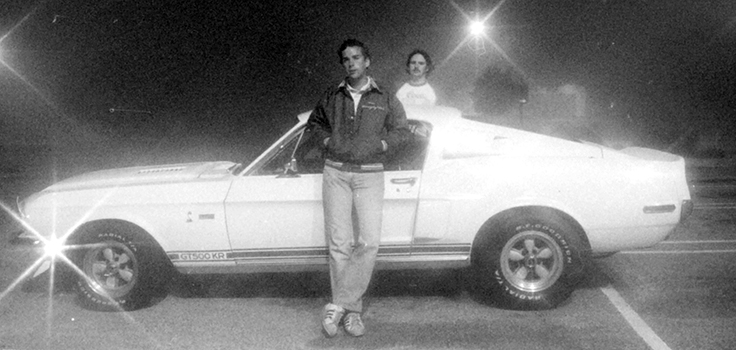

He bought other cars, including one of his childhood dream cars, a Shelby GT 500-KR. Little did we know at the time that years later he would become dear friends with its namesake, Carroll Shelby.

Probably the coolest thing we ever did was create a trio of home movies, which were shot on Super 8 film with a plotline that was stitched together on the fly. I’m not sure what inspired us to do this, but as I watch these films now – transferred to DVD fortunately — I’m glad we did. They capture us in our immortal youth — not knowing or caring then that 50 years down the road he’d be taking life’s big offramp.

The first one was called California Trash, a title that I plucked from a photo I saw in one of my drag racing magazines. Someone had gotten a beat-up old Plymouth Belvedere and painted it similarly to Butch Leal’s “California Flash” Super Stocker but had lettered “California Trash” on its flanks instead. It was a silly movie about a gang rivalry – not quite a modern-day West Side Story – that played out on four wheels as the rivals chased one another through town.

Our second film was much more refined. We called it The Boys Are Back, after the popular Thin Lizzy song of the times, and it was just Van and I — “the Boys,” as we would come to refer to ourselves — wreaking havoc and running from the law. We enlisted friends like Mike Collins (a.k.a. BOMA) and Wes Shimizu and family to play varying parts in our twisted little film. We street-raced, stole bicycles, “robbed” supermarkets and a drug dealer, did a purse snatch from a poor unsuspecting housewife (sorry, Mom), stole a car (sorry Sis), pushed old men in wheelchairs (me) off of cliffs, and even shoved a rail-sitting pier goer (again me) into the ocean while staying one step ahead of the law, which played by our mutual good friend (and future NHRA fan) Mike Takami. I did all of the stunts because a) I grew up wanting to be a stuntman and b) because Van was smart enough not to. We had a blast, but mostly it turned into an homage to our cars, which were featured prominently throughout – too prominently, said our critics, largely family members who were forced to sit through it – and driving fast. It’s an amazing time capsule.

The fast driving and drama could be tied to one of our favorite television shows, The Rockford Files, with smart-talking, fast-driving James Garner, our mutual hero.

We also loved zombie films like Night of the Living Dead, so our third and final flick was a horror film called The Boys Get Radical, which we shot one weekend day on the campus at my college. We bought a better camera — actually bought it, used it, and returned it the next day — and became George A. Romero wannabes. We had no clue how to make people look like zombies, so our undead (who were coined “gorgies” for some reason) wore pillowcases over their heads. Somehow we spent a whole day carrying a real (unloaded) rifle around a college campus “shooting” one another, and didn’t get arrested.

We started other film projects but never finished them as real life and jobs took over. Together we had taken over the writing of our CB club’s newsletter, which we transformed from a boring little handout into a sometimes-snarky, take-no-prisoners production. The club was also silly enough to make us its unofficial photographers, and curators of the club photo albums, to which he added hilarious captions. Van had always been a fan and reader of Motor Trend and I of National Dragster, and we discovered that we both were pretty good with words and cameras, and set out to become automotive journalists, combining two of our passions.

Van was the first to get some traction, landing a job at McMullen Publishing, which was a distant third behind Petersen and Argus but still a foot in the door. He did writing and photography work for their Custom Rodder and Truckin’ titles and got his boss, the rough-edged but friendly Bruce Hampson, to hire me to do some freelance articles to build up my collection of “clips” as I sought to transition from facility maintenance to journalistic gratefulness.

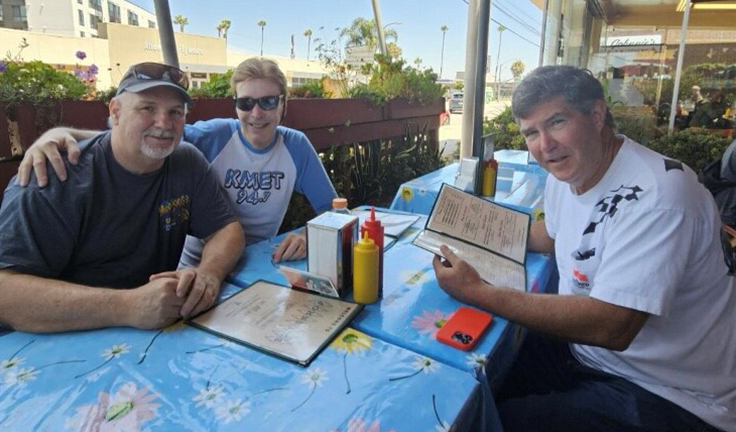

Me, Van, and Cam, earlier this year

Van went on to work for Argus at Popular Hot Rodding magazine, where he met former National Dragster staffer Cam Benty, who was the one who alerted us to an editorial opening at ND. If there's no Van in my life, there's no Cam, but there was, and the rest, as they say, is history, and while I've stayed at National Dragster for more than 40 years, Van soared far above his early jobs.

As I mentioned, he went on to become editor of Motor Trend, one of the most esteemed and influential automotive magazines in the world, and helped drive circulation numbers through the roof. His phone number was in the Rolodexes of every big player at every major automaker as they either sought to curry favor or seek advice. He became tight friends with the legendary Carroll Shelby and transitioned to television work, where he hosted ESPN’s Drive for five years, was a frequent expert guest on a multitude of shows, everything from NBC’s Today Show to The View. In 2002, he started his own production company, with the very on-brand name of “90 in a 35 Productions,” to produce automobile-themed video content. He traveled the world many times over, owned a bevy of cool muscle cars, and experienced some major adventures of which I could only dream. His friends at Motor Trend wrote a very nice tribute to him as well, with some great photos of him and thousands of his articles; you can find it here.

He was the best man at my wedding and there was an embarrassingly long and, in retrospect, horribly wasted period where he and I were so deeply engrossed in building our individual careers that we lost touch for years. Guys who had been joined at the safety belts were in different cars going in different directions. He even left California without telling me and owned a horse ranch in Texas for seven years. I mean, I know the guy liked horsepower, but not that kind. I don’t think he even had pets as a kid, and now he’s a rancher? That’s how far out of touch we were.

But somehow, magically, we reconnected about 10 years ago. He’d retired from everything except having fun. We got together, and we were "the Boys" once again. We re-watched the old movies, and, honestly, it was like those lost years never happened.

Truth be told, I started writing this remembrance long before he passed because I knew I might be emotionally incapable of doing it when the time came. I’ll never forget the email he wrote to me in early 2022 to break the news of his diagnosis. It began, in typical Van tongue-in-cheek fashion, with, “Well, the gorgies got me” and ended with, “I thought the Boys would be back forever.” That last line cracked my heart into a million pieces.

I found a lot of solace in the support he had. He had finally met “the one,” Elisabeth, the soulmate he’d longed for, and she was a strong and comforting presence for him and, honestly, both medically and emotionally, the reason he was able to keep on keeping on. Mike, who Van has known even longer than me, and his wife, Jean, moved into Van and Elisabeth’s guest house and were there to help in so many ways over the last few years. It takes a village, and Van had a good one.

From the time of his diagnosis until his passing, we had time to reconnect and remember those good times, thanks to some miracle drugs he was prescribed that extended his expiration date of a few months to more than two years, but we both knew the clock was ticking.

We got to visit a lot — not near enough — and took some final cruises together. He got himself a bad-ass Shelby Cobra replica, a Kirkham 427 considered by real Cobra owners to be the most accurate of all the replicas and a car that feels ready to rip your eyelids off. With no roof and only lap belts, I would have been half-scared to death with anyone else behind the wheel, but my buddy has had so much experience in fast cars and on racetracks that I trusted him implicitly. He also bought the '68 Dart GTS convertible used in the Mannix TV show, another of his longtime favorite television detective shows. He had so many cars that he installed lifts in his garage to accommodate more of them at home, where he could drive them.

I’ve known a lot of “car guys” over the years, but few as passionate as Van. He loved all kinds of cars, but especially ‘60s muscle cars. He could talk the talk, and when it came to planting his foot on the gas, he could walk the walk.

Over the past two years, Van had secretly hatched a plan to find a blue ’75 Monza like his old cruising vessel and restore it as close as possible to his original. As you can imagine, finding a near-50-year-old model can be tough, but he finally did, and the car had quite a heritage. It belonged to Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, who had found and restored it to relive his own teenage memories. Van bought the car at an estate sale, and although it wasn’t the exact same shade of blue, it was close enough. Van put dish mags and BF Goodrich Radial T/As on it, just like the old car.

The Allen car didn’t have a 350 when Van bought it, so he had one professionally built and shoehorned into the engine bay, mated to a 4-speed transmission. (Van’s original had an automatic.) He kept this project under deep wraps while he worked on it because he wanted to surprise me, and, boy, did he. So, we went cruising (after an obligatory burnout).

When I slipped into the passenger seat as I had done so many times decades ago, it was like coming home. We cruised around our old haunts for hours like it was the 1970s all over again, went by his old high school and snapped some photos, and he’d stop every now and then to fine-tune the carb. Yeah, a real car guy who knows how to work on them, too.

We stopped for Jack tacos — just like the good ol’ days — and talked about life, and what he was facing as the medical prognosis kept getting worse. It was then that he told me that he’d built the Monza for just that day. He also was able to finish and share with me a screenplay he'd been working on that was loosely based on our friendship. I'll treasure it.

I’ve read many obituaries that told of someone’s “brave battle” with cancer but didn’t know what that really meant or looked like until I lived through it with Van. He never did the “Why me?” thing — although as a lifelong non-smoker one could certainly agree that lung cancer was a cruel fate worth asking that question — reminding us that many others also had debilitating or fatal diseases that they didn’t deserve. He was unflinchingly kind to his doctors, especially his oncologists, always striving to be the perfect patient “because their job is already hard enough.”

When the medical options dwindled to potentially painful and terrifying remedies that might only extend his time briefly and certainly uncomfortably, he opted out, choosing quality over quantity. He did what C. Van Tune has always done. He buckled his belts, set his jaw, and steered the perfect line as powered into the final few curves of his life with the wheel in his own hands.

As his time began to get small, and the realization of what was to come became more real, I turned, like I always do, to comfort in music. Both Don Henley and Bruce Springsteen had evoked similar thoughts in recent songs about people having only “just so many summers, just so many springs” in their lives, and Van had maybe seen his last of each.

And it was Springsteen who threw me an emotional lifeline on his newest album, Letter To You, whose theme is about lost friends as he reflects on being the last member of his original band still alive, and the song “I’ll See You in My Dreams."

The lyrics are so good and struck a chord with me.

The road is long and seeming without end

Well, the days go on, I remember you my friend

And though you're gone and my heart's been emptied it seems

I'll see you in my dreams

I’ve got your guitar here by the bed

All your favorite records and all the books that you read

And though my soul feels like it's been split at the seams

I'll see you in my dreams

When all our summers have come to an end

I'll see you in my dreams

We'll meet and live and laugh again

I'll see you in my dreams

Yeah, up around the river bend

For death is not the end

And I'll see you in my dreams

The guitar and the records and the books are all exchangeable metaphors for keepsakes and memories left behind, and those memories do not die, which is why I love “death is not the end,” and, without getting all metaphysical, I hope there is something after death where we can be reunited. Our road together was long, and we never thought we’d reach the end where we’d continue on separate paths.

Even though he’s not the sappy soul I am, I asked Van and Elisabeth to listen to the song with me on one of our final visits, and I hoped it would resonate with him. I think it did. It’s how I’m gonna feel and think and dream. The last time I saw him was at his bedside, we hugged and cried and reveled one last time in how long and great and true our friendship had been.

Until we see each other again, keep the engine running and the tires warm, Van.

Right-o. Night, my brother.

In lieu of flowers, philanthropic gifts in memory of Courtland Van Tune can be made to Moores Cancer Center Fund # 7731. Philanthropic gifts will support the work of Dr. Luda Bazhenova.

Phil Burgess can be reached at pburgess@nhra.com