Cars that changed drag racing

A big part of our story as human beings is carved in our past, begging the inevitable question of “How did we get here?” Whether that’s the story of human evolution, mass manufacturing and marketing, social media, or your own family tree, I think it’s important to study the road you’ve traveled.

In a sport like ours, where evolution carried us from stripped-down Model Ts to 330-mph Top Fuel dragsters, if you traveled down our road from the late 1940s to Jan. 29, 2021, parked along the roadside like milestones would be the machines of our past. Some would be orderly parked, pulled to the side of the road to make room for The Next Big Thing, some would be smoldering hunks of failure, and some would be upon pedestals as monuments of success. It’s the latter that I’m addressing today.

Quite simply: What are the cars that changed drag racing?

Before you start licking your lips in anticipation of an agree/disagree column, I’m not there yet. It’s going to be the subject of a future NHRA National Dragster story (that inevitably will end up here, too), but first the research and introspection. I’m sending out an email to a cadre of drag racing experts for their input and insight, but I also want to crowdsource this through the Insider Nation. We all come from different backgrounds, with loves and knowledge of different classes and eras, and I want this piece to be as representative as I can, so I want you to weigh in, too.

Obviously, there’s a lot of low-hanging fruit to pick.

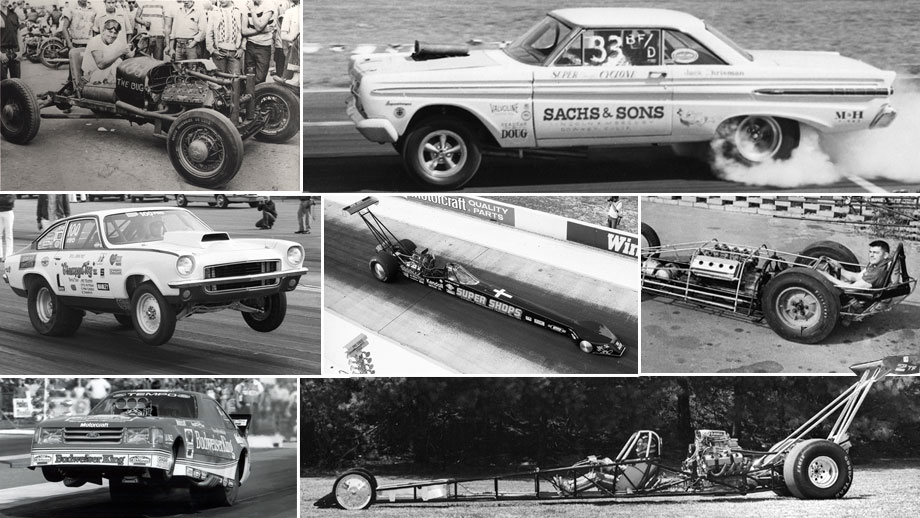

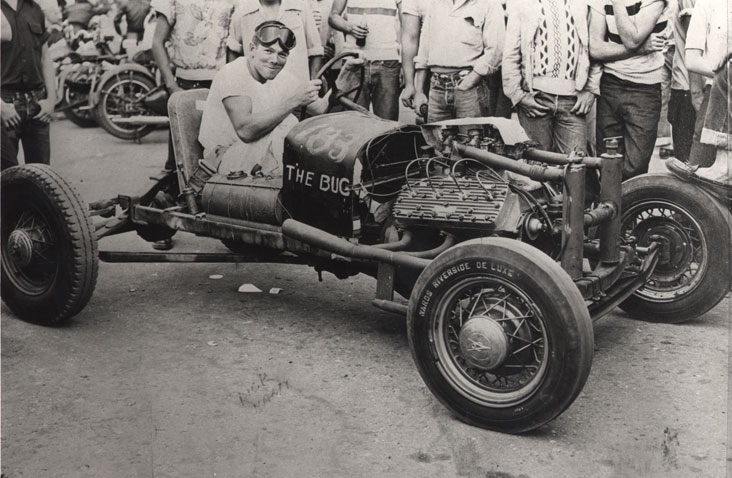

Dick Kraft’s “The Bug” seems an obvious place to start. It’s widely recognized as the first “dragster” because of its stripped-down nature. It started life as a ’27-T then was stripped down and turned into a farming tool as a weed sprayer in the Kraft family’s orange groves. Although the car was designated as a roadster when it first ran at the Santa Ana Drags in 1950, its bare-bones nature — save for the lone seat (from a B-17 bomber) bodywork was minimal — saved weight but also created a blueprint.

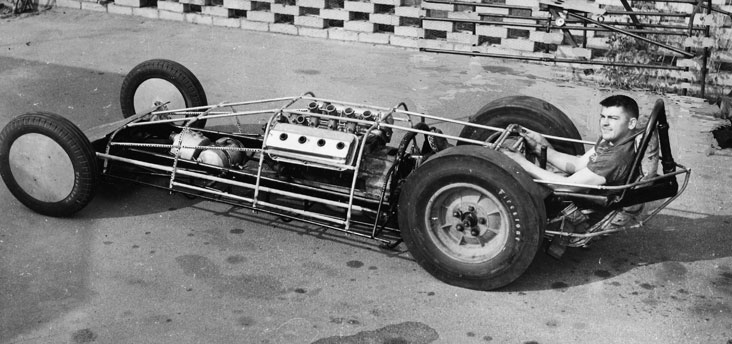

After that, you have to think about Mickey Thompson creating in 1954 what was arguably the first slingshot dragster, with the driver over and behind the rear end for maximum weight transfer, or Ed Cortopassi’s Glass Slipper, which showed what aerodynamics could do for a drag car.

I think about a lot of that early iron that cut bold paths through the jungle of ideas; the concepts didn’t persist, but they showed us what was possible, including Lloyd Scott’s dual-motored Bustle Bomb, the aircraft-engined Green Monsters of the Arfons boys, Jack Chrisman’s rear-engined, chain-driven Sidewinder dragster, Eddie Hill’s Twin Dragon side-by-side twin, and Tommy Ivo’s four-engined Showboat.

The Dragmaster Dart certainly has its place in the history books, showing that a mass-produced design could allow a technologically advanced and readily purchasable product could create legions of instant dragster teams who didn’t know how to weld in their garages.

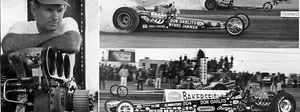

Diving into the 1960s, you think about cars like Don Garlits’ Swamp Rat V, with its innovative wing that showed that more airplane technology could work on drag cars to enhance downforce. It was a major leap from the makeshift plywood wind foil on the Jack Chrisman Twin Bears machine.

Certainly, innovative machines like the Sachs & Sons Comet, the first supercharged nitro-burning doorcar and the forefather of the Funny Car, or Don Nicholson's Eliminator I Comet, the first flip-top Funny Car, should be included, right? And, of course, we can’t forget the famed Mickey Thompson ’69 Mustang, the first narrow-framed flopper, or the Chi-Town Hustler that showed us how cool (and beneficial) long, smokey burnouts could be.

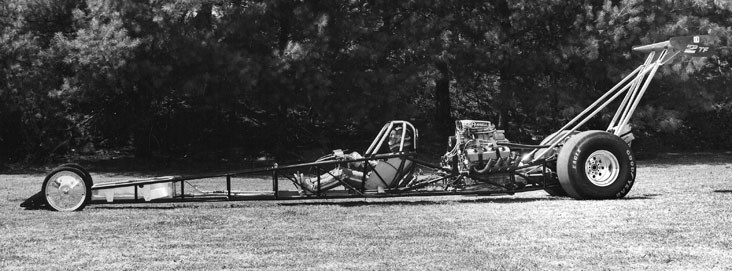

In the ‘70s, the most recognizable step forward again came from Garlits with Swamp Rat 14 in 1971, the first rear-engined Top Fueler to win a national event. There had been many predecessors with varying levels of success but Garlits’ Winternationals win cast a die that lives on today.

In Pro Stock, Bill Jenkins’ '72 Vega, with its partial tube-frame construction, certainly pushed that class forward in leaps and bounds as teams began to realize that their repurposed Super Stock cars weren’t going to cut it as competition increased and e.t.s decreased.

What about Jerry Ruth’s '80 Top Fueler, built by Al Swindahl, that further updated and innovated the Top Fuel design with a wider roll cage and other improvements? I think that at some point in the early 1980s, most of the top dragsters were Swindahl-chassised.

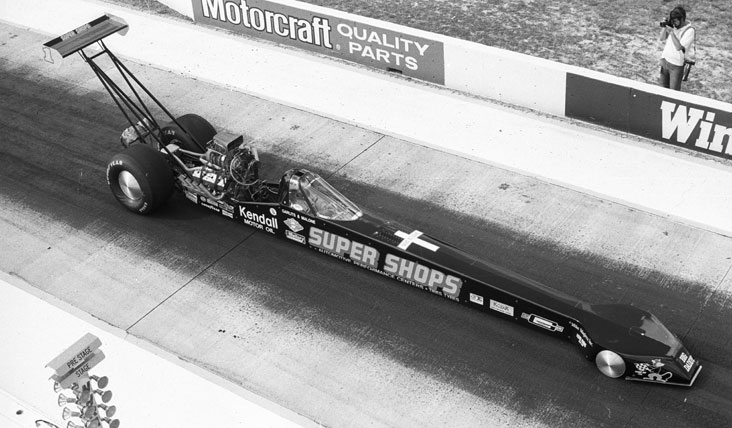

The Swindahl chassis was also the platform for another forward-thinking and still-current technology when Tim Richards bolted the first tall, laid-back rear wing on Joe Amato’s car before the 1984 Gatornationals. Taking advantage of the rules of physics and leverage, it changed the profile of the class virtually overnight.

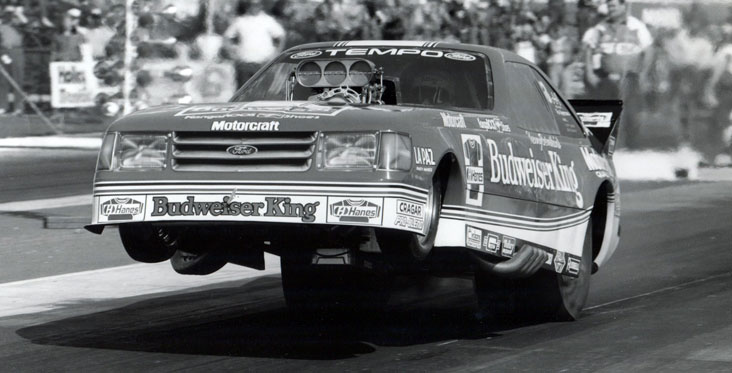

1984 was also the year that Funny Car aero really took off. Cars had been in the wind tunnels before, but nothing like what Kenny Bernstein and genius crew chief Dale Armstrong did. The '84 Budweiser King Tempo, with its rounded edges, full side windows, belly pans, and other tricks, showed the class a bold and sleek new way forward. You could also say the same thing about the '86 Bud King with its development of the multistage clutch or even the much-derided '87 “Batmobile” that showed thinking that while technically legal was beyond what the rulebook meant and fostered even more ideas and understanding about aerodynamics and is a direct descendant of today’s impressive rear-deck Funny Car spoilers.

Although not the long-lasting technical success of some of the others listed, Gary Ormsby’s Castrol GTX streamliner and Garlits’ same-year Swamp Rat XXX from 1986 opened our minds to working closely with innovators in other forms of motorsports like Mike Magiera and Eloisa Garza and the use of new composites. And, of course, Garlits’ cockpit canopy idea is still used on all of the current Don Schumacher Racing dragsters, and Magiera wings are the choice of many top teams.

And what about the '85 Don Ness-built Pro Stockers of Butch Leal and Frank Iaconio, the first cars in the class to have a “Funny Car-style” roll cage? Yep, a design still very much in use today in the class but revolutionary at the time.

What about Gene Snow’s '88 Top Fueler, the first modern-era car to toss out the transmission and use direct drive mated to a multistage clutch (and made NHRA's first four-second Top Fuel pass), or Jim Head’s same-year Funny Car that carried it steps further? Those basic mechanical principles are still in place even as teams kept stacking more and more clutch discs inside the bellhousing.

Those are the most obvious changes and cars, and one could understandably argue that as the classes have become more standardized and the window for intervention narrowed to constrain costs and headache, the paths to success in each class have followed the same road. In Pro Stock, today that means a Chevy Camaro. They all look alike from the outside, but you know there are innovations under the hood that we can’t see, and they sure as heck aren’t going to share. You could say that, outside of the Schumacher canopy cars, all Top Fuelers look the same, but we know there are variations in chassis to allowed flex and bow that suits each team, and slip-tube frames to make it all work.

But between every paragraph above, there are probably countless cars that changed the sport in different ways, some obvious, some not so obvious. Which of the above do you agree with? What did I miss? I’d like to hear your thoughts. Hit me up at the email address below. Thanks, as always, for playing.

Phil Burgess can be reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE