NHRA vs. NASCAR at Daytona Beach

This article, written by Wally Parks, originally appeared in the March 16, 2007 issue of NHRA National Dragster magazine.

It was a fun time 50 years ago when Ray Brock and I covered the 1956 NASCAR Speedweek action in Daytona, Fla., for Hot Rod magazine. The action included speed trials on the sand conducted by a local businessmen’s group called the Century Club, most of whose members were happily competing for a targeted 100 mph.

It was a time before Daytona Speedway had been built and a time when NASCAR’s stock car races were run on a circuit south of town that included a stretch of paved roadway and two rough-and-tumble turns onto a long beachfront straightaway at the ocean’s edge.

Early in 1957, we heard of a new class that NASCAR was adding to its Speedweek agenda called “Experimental.” The class was designed to attract participation from the auto factories, but it was also open to private entries. Knowing little more than that, our immediate reaction was, “That’s for us!”

With barely two weeks’ time for planning and preparation before hooking whatever we’d have to Ray’s Oldsmobile for the long tow from California to Florida, we contacted our good friends at Plymouth in Detroit and gained their approval for a “loaner,” a 1957 Plymouth Savoy two-door coupe that we drove right off the production line at Chrysler’s old East Los Angeles assembly plant.

Ray was our project engineer, but I selected the color: light yellow to contrast with sea, sand, and sky for distinct photographic advantage. With so short a time to convert and prepare the car for participation in the speed trials, which would consist of two-way timed runs through a one-mile course on the Daytona Beach sand, Ray kept modifications to a minimum. One shortcut was to borrow a Chrysler Hemi from Harry Duncan, a contractor friend who had prepared it for Ed Losinski’s dragster.

The engine had Hilborn fuel injectors and a Scintilla Vertex magneto. Bob Hedman handcrafted a set of headers for us, with open pipes tucked back cleanly under the car. Through his contacts in Akron, Ohio, Ray got a set of Firestone racing tires — 7.10/7.60-15 in front and 8.90-15 in the back for which he had rear wheels with wider rims made.

We removed the car’s back seat and the passenger-side seat back, then installed the necessary roll bars, seat belts, and fire extinguisher for driver’s protection. For engine cooling, Ray replaced the radiator with a 10-gallon tank, mounted in the trunk and connected to the engine via long two-inch-diameter tubes. As an added thought, for traction advantage, he filled the stock gas tank with water. Our fuel supply for the timed runs was contained in a five-gallon Moon fuel tank mounted on the floor, its hand pressure pump within easy reach of the driver.

Only one modification was made to the chassis: replacement of the Plymouth front torsion bars (new that year) with a heavier Dodge unit. To its credit, the new torsion-bar suspension proved a godsend when ironed out on the less than smooth beach surface for our two timed runs.

When all was assembled, we took the car to Tony Capanna’s Los Angeles Wilcap shop, where the Hemi, after being fine-tuned by Tony on his dynamometer, was installed. As an extra precaution, he added a set of rubber tubes that fed into the fuel injectors, “to cool the charge,” he said. But latent rule changes limiting fuel to high-test gasoline made them unnecessary, so we presented them to the Ford team. We then pushed the car out of the shop, and, as its designated driver, I got in and fired the engine for a short chirp down the alley -— its sole run under power until leaving the starting line on Daytona’s beach. Then we hooked it to the tow bar and took it to a Hollywood sign shop for its lettering. The complete conversion time was 10 hours.

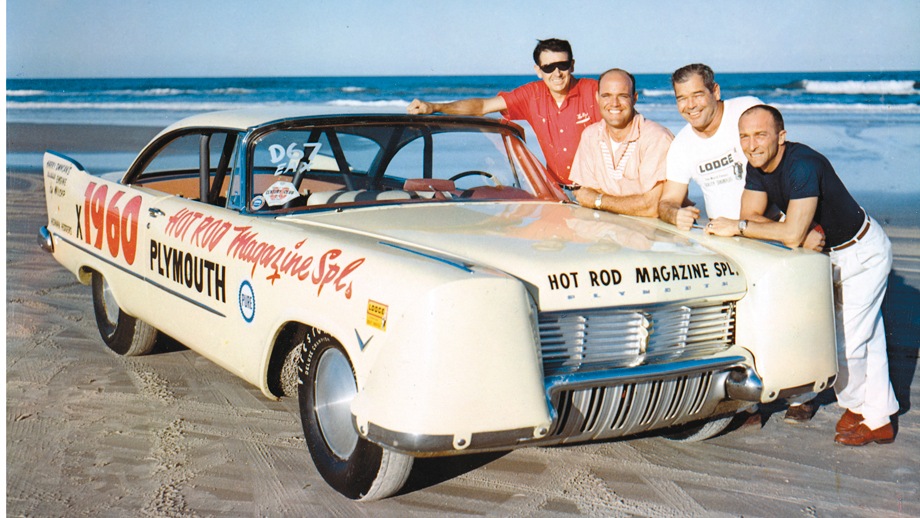

We had filed our entry for the car as the Hot Rod Magazine Spl. and named it “Suddenly” after Plymouth’s 1957 sales slogan, “Suddenly it’s 1960!” No question about it, the lettering stood out against the yellow.

From start to finish, under Ray’s round-the-clock direction, we had transformed a ’57 Plymouth into a race car ready to prove its mettle.

By the time Ray and Bill Likes, his companion on the trip, arrived in Daytona, we had made arrangements with a local Chrysler dealer to use space in his garage. A long night’s final details included fashioning an aluminum belly pan that fit snugly beneath the chassis. It was done under the supervision of metal craftsman Whitey Clayton, who had also made a pair of unattractive aluminum eyelids to cover the headlight cavities.

The next morning we heard rumors that the beach was rough from an overnight Nor’easter wind, and with a few last-minute adjustments to be made on the car, I opted to go downtown to NASCAR’s headquarters and inquire. I was assured by Bill France Sr. that it was doubtful any runs would be made that day on the still-rough beach. I decided to drive over to the beach for my first look at the course before returning to the garage. Up on a sand dune by the finish line, I climbed a makeshift control tower to look for the new timing system NASCAR had allegedly purchased from USAC, which wasn’t there. But in looking northward, up the course, I could see a long line of cars at the starting line getting ready, apparently, for their timed runs. My next move was to find a phone booth and alert Ray to my discovery and urge him to bring the car over as quickly as possible. Meanwhile, I had located the official Pure Oil gasoline fueling station and was waiting there when our car finally arrived.

But there was one more surprise: The attendant official told us, “You ain’t got no X,” whatever that meant, adding that we would have to go to a nearby drive-in theater site to have our X applied. Reporting there, with “Suddenly” still in tow, we learned that we didn’t have the required NASCAR memberships, which took a bite out of our limited budget. But we complied and got our official entry clearance, consisting of a big masking-tape X on each side of the car, and we were ready to go.

Because we were only about a mile inland from the beach, we decided to fire the engine while still on the tow bar, just as a warm-up. I climbed in to get a feel for what the maiden voyage might be like. No better music could I have ever imagined than the sound of those big exhausts resonating from under that handmade and hidden belly pan!

When we arrived at the fueling station, we were at the back of a long line of cars, waiting their turns for a run through the mile-long course, which I still hadn’t even seen. While the guys were changing spark plugs, I strolled up to the starting line to check the procedures. A long black cable about two inches thick stretched away toward the finish line. The cable was connected to a device on a broom handle, held by the official starter, and inserted under each car’s front wheel as the car rolled away. It was different from any system we had ever seen in SCTA’s speed trials, and that it sank into the sand seemed not to matter.

Little by little, our Plymouth was working its way forward to the starting line, and as it approached, I eagerly climbed in and prepared myself for whatever. Belt fastened, helmet and sunglasses on, recheck of controls — all seemed in order. While waiting there, one of my friends on the Ford team who had just made a run came up to the car and shouted hysterically, “Wally, don’t do it! The course is too rough!” But shortly thereafter, another friend, Art Chrisman, also on the Ford/Mercury team, came by and confirmed a fair-sized dip about halfway through the course but added that if one stayed close to the water’s edge, it should be okay.

And then it was our turn to go. With a short push-start by Ray’s Olds, “Suddenly” was on its way under its own power and headed for who knew what. I’ll confess that I feathered it a bit on that first leg, and I paid more attention to the oil-pressure gauge than the tachometer. (Tony had warned me before leaving, “If the oil-gauge needle even bobbles, back off!”) And how was the ride? It couldn’t have been more assuring. As for the dip, our suspension didn’t even know it was there.

We didn’t know what kind of mileage to expect with our five gallons of gas in the little Moon tank, but on inquiring before our run started, we were assured that gasoline would be available in the turnaround area. On arrival there after the run, no such accommodation was available, and even our friends with the other team cars declined to help us out.

Our speed on the south run had been 153.453 mph — faster than any of the others. With no gas available for refueling, we didn’t even remove the tank cap to see what might be left. After a short wait while the others were making their return runs, “Suddenly” was on its way back, with me full of confidence and flooring it on the northward leg of the two-way timed mile. No ride has ever felt so good, before or since!

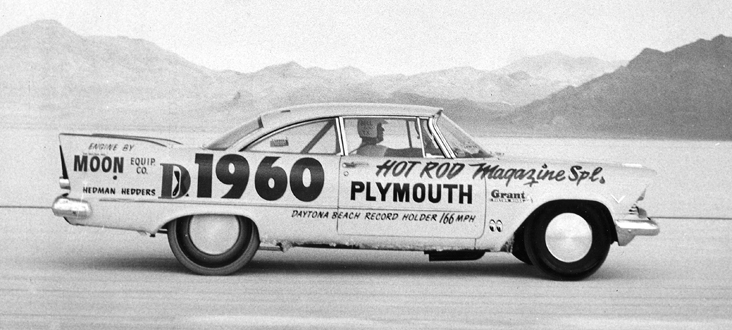

As I passed the brave flagman at the mile marker, I knew I was on my way to a good run. I even took time to steal a glance away from the unwavering oil gauge to the tachometer at a top speed of 166.898 mph for a two-way average of 160.175 mph on less than five gallons of gas.

Slowing at the run’s end, with Ray following closely behind, we headed for the starting area, where the media and photographers were assembled. But, surprise of surprises, no sooner had we arrived there than a monitor in a striped referee shirt climbed aboard and notified us that we would need a fuel certification before any record could be declared.

That seemed reasonable, and we were unconcerned — until he told us he had to escort us to the fuel check. So with tow bar reattached and the monitor aboard, we were escorted clear across town to an empty armory, where we were told to wait for the fuel certifier. It was getting dark, and we hadn’t eaten all day, but we waited for what seemed hours.

Finally, an official whom we didn’t recognize stopped by, but he had no authority, he said, to certify fuel. We waited some more, and a higher-ranked official came in. He, too, had no authority to conduct fuel tests but said someone would come along soon.

The next visitor was none other than NASCAR Vice President Pat Purcell, whom we’d gotten to know. Pat advised us that only “Big Bill” had the authority to perform and certify fuel tests. He assured us that we could count on Bill France Sr. stopping in to conduct the essential test.

Sure enough, some time later Bill Sr. strolled into the armory and asked, “What’s goin’ on?” We replied that a fuel test was needed before our record performances could be confirmed, and we showed him the Moon tank’s still-sealed filler cap, which he examined.

[Pictured right: Bill France Sr. and Wally Parks]

Then he did an astonishing thing: He stuck his big, long finger down into the tank’s neck, raised it to his nose, sniffed it, and said, “Yep, that’s gas.” Then he walked out of the armory. That was it; we were legal.

As it turned out, we had set the all-time fastest speed for a closed-bodied car on the beach, but further, “Suddenly” had set the official record for NASCAR’s new Experimental class, outrunning the best teams Detroit could muster as well as a mind-boggling collection of individual and factory-backed private entries.

Among other contenders were Zora Arkus-Duntov with a pair of far-out Chevrolet Corvettes, two Lincoln-powered streamlined T-birds, Andy Granatelli’s fuel-injected Chrysler 300, Smokey Yunick’s ’57 Chevy pickup, and numerous other factory-backed and private-entry teams.

The list of Experimental-class top speed averages featured familiar names in the hot rod fraternity, including our ’57 Plymouth’s 160.175 mph; Art Chrisman, ’57 Mercury streamliner, 154.176 mph; Fran Hernandez, ’57 Ford, 142.800 mph; Chuck Daigh, modified T-bird, 152 mph; Vern Houle, ’57 Mercury, 146.759 mph; and Karol Miller, ’56 Ford, 146.759.

Without question, our mildly modified ’57 Plymouth Savoy, with its application of dry lakes know-how by Ray Brock and a small cadre of hot rodders, was the clear dominator at NASCAR’s 1957 Speedweek, taking home the trophy and some subdued accolades for having blown away the factories’ best efforts. The only outside media recognition we received was in the Daytona newspaper the next morning that covered Speedweek most extensively, bannering the headline “Parks sets record in Hybrid.” It wasn’t until years later that we realized the dent we had blindly made in NASCAR’s factory-performance plans.

Win some, lose some. But a few months later, running “Suddenly” in speed trials on Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats with a Hemi engine borrowed from Dean Moon and on a light fuel mixture, Ray recorded a top speed of 183.00 mph, which at that time was a very outstanding performance.

Today, a re-creation of “Suddenly” sits proudly in The Wally Parks NHRA Motorsports Museum at Fairplex in Pomona, attesting to its simple but functional concept in 1957 and the confidence that pulled it all together.