Late-night finishes

So there we were, me and K-Mac, eyes glued to the starting line, eliminations ladders in hand, pens at the ready, keyboards awaiting an onslaught of fast fingerwork that would make Elton John envious. Brittany Force and Richie Crampton, in position, started motors attached, crewmembers ready for action, the fans ready for round one of Top Fuel. It's 11 a.m. Sunday. Fire the first pair!

|

We were back in Topeka last weekend for our annual gee-I-hope-there’s-not-a-tornado-while-I’m-here weekend of NHRA action (out-of-state Winternationals fans probably do the same thing with earthquakes), where you always keep an eye on the sky. Even though it had rained that Sunday morning, the NHRA Safety Safari had the track dried, prepped, and ready on schedule at 11 a.m. Then it started drizzling. Then it started raining and pretty much didn’t let up for the next five hours.

When we got the announcement that we’d start racing at 7 p.m., we all did some quick math and figured we were in for a midnight-or-later finish and girded ourselves for an all-nighter. Rain delays are always interesting, especially when they reach epic proportions, because you start looking around at your fellow castaways and know that some day (not at moment, as NHRA social media queen Nykki Schele pointed out here) you'll all have a great road-warrior story to tell about the time you stayed up all night and drove straight to the airport.

The delay did give me time to think back on another late-night finishes in NHRA history, and the one that immediately came to mind was the 1975 Summernationals, which is better remembered as being the site of “Jungle Jim” Liberman’s first (and only) national event Funny Car win than for the hour of its completion.

After a full day of racing Friday, rain blanketed New Jersey for most of the next two days. The only break in the rain was a two-hour window Sunday, which NHRA officials used for one more qualifying session. Monday dawned no better, though the NHRA Safety Safari and Raceway Park teams nonetheless continued a Sisyphean battle to dry the track between showers. NHRA had in its arsenal for the first time a jet track dryer (sponsored by Thrush mufflers) built for them by longtime jet racer Romeo Palamides that complimented a jet that the track already had. They also brought in three airplanes -– the track is adjacent to an airport -– that taxied up and down the strip with their engines helping push water around.

After a full day of racing Friday, rain blanketed New Jersey for most of the next two days. The only break in the rain was a two-hour window Sunday, which NHRA officials used for one more qualifying session. Monday dawned no better, though the NHRA Safety Safari and Raceway Park teams nonetheless continued a Sisyphean battle to dry the track between showers. NHRA had in its arsenal for the first time a jet track dryer (sponsored by Thrush mufflers) built for them by longtime jet racer Romeo Palamides that complimented a jet that the track already had. They also brought in three airplanes -– the track is adjacent to an airport -– that taxied up and down the strip with their engines helping push water around.

The New Jersey fans were incredibly resilient, too, with an estimated 11,000 of them on hand once eliminations did finally kick off at 6:30 p.m. Monday evening.

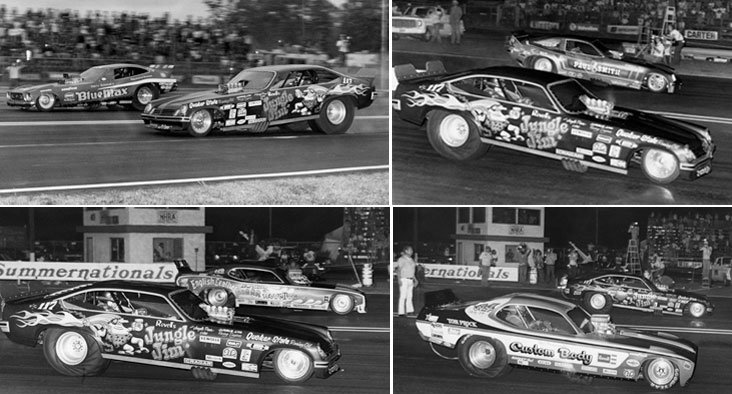

Don “the Snake” Prudhomme – a perfect three-for-three already that season after wins in Pomona, Gainesville, and Columbus -- qualified the Army Monza No. 1 in Funny Car with an early shutoff 6.22, with Gary Burgin (6.29), Kosty Ivanoff (6.34), and Liberman (6.37) rounding out the top four of 16.

While “Jungle” remains revered as one of the greatest Funny Car drivers in the sport’s history – showmanship, performance, and driving ability all wrapped up into one – he wasn’t exactly a regular on the national event tour, which explains his single-digit win total. In fact, according to stats guru Bob Frey, Liberman competed in just 19 national events over nine seasons -– the four he ran in 1975 were the most he’d ever run in one year –- because he made his living, and his reputation, on the match-race trail.

He had come close the year before, reaching the final round in Englishtown only to launch into a large wheelstand while leading in the final round against Al Segrini. Although, in true “Jungle” fashion, he remained in the gas for longer than most, he couldn’t hold off Segrini’s wheels-down pace.

Segrini didn’t even qualify at the 1975 event, nor did reigning world champ Shirl Greer or former world champ Gene Snow, and when Prudhomme was upset in round one by teammate-turned-rival Tom McEwen, the die had been cast.

Liberman, who a week earlier at a Maple Grove Raceway won for the fifth time in six races there, continued his hot streak when he survived a pedaling match with Raymond Beadle and the Blue Max Mustang II, winning on a 7.027 to 7.023 holeshot.

Paul Smith, who had finished second behind Greer for the 74 championship, then lost traction against “Jungle” in round two and crossed the centerline. Liberman then showed that he, too, had power, outrunning “the Ace,” Ed McCulloch, with a 6.42 to reach his second straight E-Town final.

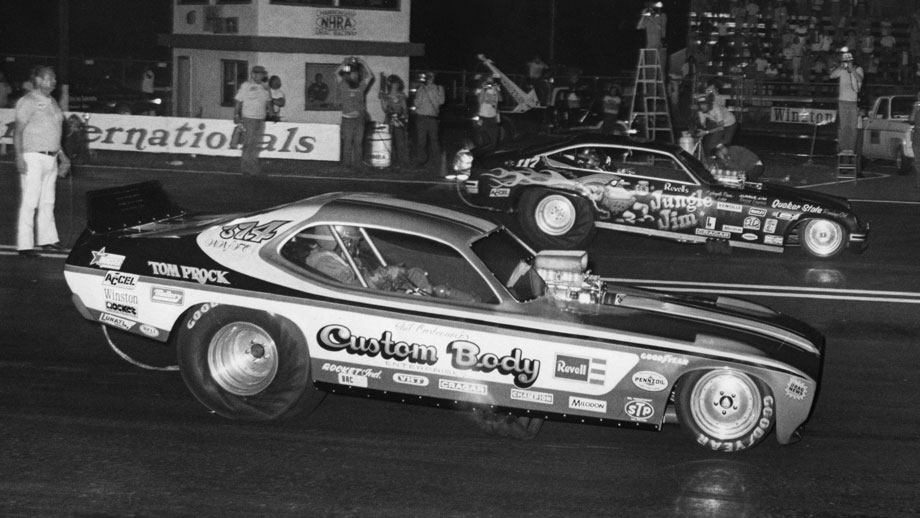

Waiting for him there was Tom Prock and the Custom Body Dodge. Prock, who a week earlier had been the star of E-Town Fourth of July event (including a victory over Roy Harris in Liberman’s second car the same weekend “Jungle” was winning at Maple Grove), was in the midst of perhaps his best year ever, having been runner-up to Prudhomme in Gainesville and runner-up to Prudhomme in Montreal at the race after the Summernationals en route to his first Top 10 finish. Prock was loaded for bear, but yanked the front end off the ground, negating steering control, and when he got too close to Englishtown’s famed no guardwall/all-grass lane edging, he had to lift and watch Liberman power to a 6.49 victory.

Waiting for him there was Tom Prock and the Custom Body Dodge. Prock, who a week earlier had been the star of E-Town Fourth of July event (including a victory over Roy Harris in Liberman’s second car the same weekend “Jungle” was winning at Maple Grove), was in the midst of perhaps his best year ever, having been runner-up to Prudhomme in Gainesville and runner-up to Prudhomme in Montreal at the race after the Summernationals en route to his first Top 10 finish. Prock was loaded for bear, but yanked the front end off the ground, negating steering control, and when he got too close to Englishtown’s famed no guardwall/all-grass lane edging, he had to lift and watch Liberman power to a 6.49 victory.

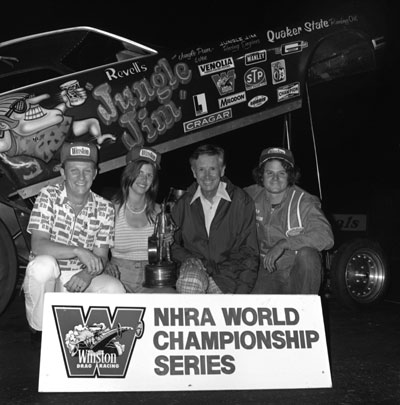

If you've ever seen the wonderfully introspective interview that "Jungle Pam" Hardy did with Bobby Bennett, you know that Liberman wasn't a big fan of running national events, yet when I spoke to her earlier this week, she said that the Englishtown win was very meaningful to him.

"He was thrilled," she said. "I think he felt vindicated, that is was all worth it. He made his money on match racing because national events didn't pay much, but winning a national event meant that his talents were fully recognized on a national stage. He got a lot of ink over those two final rounds in Englishtown. And the fact that it happened in front of a hometown crowd -- those people loved him -- made i even more special." (You can read more of her thoughts about "Jungle," as well as some more in-depth info about him, in this column I wrote a few years ago.)

Even though Liberman only won the one event and has two finals, that's still a pretty good record for just 19 events. Makes you wonder how history might have changed had he dedicated himself to running more national events.

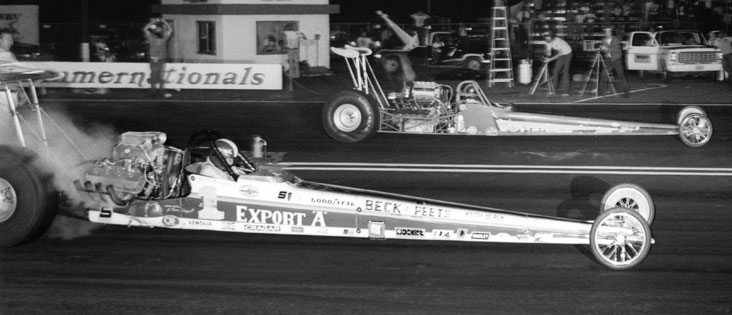

The event also will be remembered as the first win by another Jim, Jim Bucher, who earned the last Top Fuel win by a Chevy-powered machine (depending on whether you count Stan Shiroma’s ’77 Seattle win with the Chevy-influenced Rodeck) when he upset reigning world champ Gary Beck’s Export A dragster. Bucher, whose Chevy had set the national record at 6.07 at the 1973 Gatornationals en route to a runner-up there and another at that year’s Summernationals, looked like a longshot until Beck’s potent machine developed an oil leak that coated the rear slicks, allowing Bucher to win with an otherwise beatable 6.57. Beck had earlier made runs of 6.07, 6.09 and 6.15 while Richard Tharp had qualified No. 1 at 5.97 in the Carroll Bros./Texas Whips entry (E-Town’s first five-second run) but lost in round one to John Wiebe.

The event finally completed after 1 a.m. and it was well after 2 a.m. before the winner’s circle festivities were complete, making it one of the wildest all-nighters in NHRA history.

Topeka has its own late-night story to tell as the 1998 event featured a 1:15 a.m.-ish finish after a scenario similar to this year. Racing Sunday didn't start until well after 6 p.m. and concluded at almost 1:30 a.m. with Cory McClenathan (Top Fuel), Ron Capps (Funny Car), and Warren Johnson (Pro Stock) in the winner's circle. Capps had a bit of a harrowing ride in defeating Al Hoffman as the crankshaft of his Roland Leong-tuned Cope Camaro broke, leading to a fire that singed both sides of the black body.

It was only Capps' second season in the class, but the Topeka win was already his seventh in Funny Car and his fifth that season, Points leader John Force had lost early, so the win pulled Capps to within two rounds of Force as the season wound down (Topeka was held in the fall then, and was the fourth-to-last event of the season).

It was only Capps' second season in the class, but the Topeka win was already his seventh in Funny Car and his fifth that season, Points leader John Force had lost early, so the win pulled Capps to within two rounds of Force as the season wound down (Topeka was held in the fall then, and was the fourth-to-last event of the season).

"We're thinking about that big bad [championship] ring at the end of the year right now," he said back then. "There's no reason why we can't win it, no matter what happens we're going to shoot for the championship."

Unfortunately for Capps, as we know all too well, he'd have to wait a long time -- like 18 years -- to finally get that championship. He finished second in 1998 (the first of four championship runner-ups before his coronation), but he'll always have Topeka 1998.

Topeka 2018, as you’ve probably read, didn’t end with an early-morning finish as the impending return of rain caused NHRA officials to call a halt to the proceedings after the second round. I didn’t get to stay around for Monday’s finale as, in the interest of the budget, we kept our original early-Monday flights and left behind a skeleton crew to cover the action. We missed one of the wildest runs of the season, a rare Top Alcohol Dragster blowover by Steve Collier. The Collier family has been on my radar the last year for the amazing success not just of Steve, but son Koy and brother Jack in the division 4 Super-class categories. This wreck is obviously a setback to their expansion into the alcohol ranks, but we’re glad that Steve wasn’t seriously injured.

It’s been a long time since we’ve seen a blowover, especially in the Alcohol class (Kate Harker in 2007 in Sonoma being the latest I could think of) and Collier’s looked the same as the more than a dozen we’d seen since Eddie Hill backflipped his Pennzoil dragster at the 1989 Winternationals. The car goes into a wheelstand, catches air, gets airborne, corkscrews and rotates 180 degrees horizontally, and somehow lands on all four wheels facing backwards. I guess it’s got something to do with the gyroscopic effect of the rear wheels spinning in mid-air.

Longtime readers of this column may remember the multi-part series I did on Top Fuel blowovers back in 2012 that might be fun for you to revisit in the wake of Collier’s flip. There are some great photos and even some video. Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

Phil Burgess can reached at pburgess@nhra.com