Fighting fires

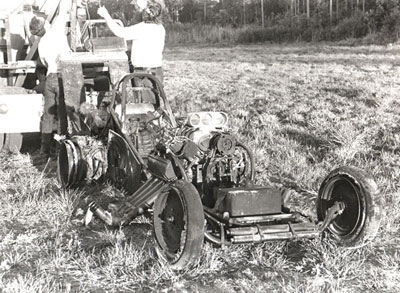

(From above) Funny Car racers Jim Adolph, Shirley Muldowney, "Cogo" Eads, Barry Kelly, Ron Fassl, Butch Maas, and Jim Nicoll suffered nasty fires in '72-73.

(Top and bottom photos, Leslie Lovett; all others, Steve Reyes) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

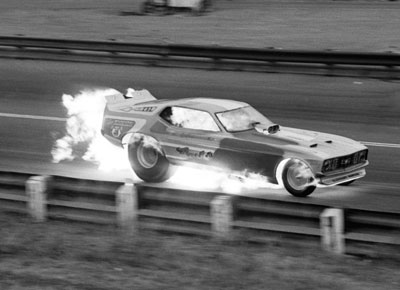

Friday’s column about John Force’s “firefighting Funny” and the rules changes that have followed made me want to wade back into the history a bit to talk about the longtime scourge of the Funny Car set that Whit Bazemore once famously described as “like riding inside a Molotov cocktail.” After dragsters and gassers dominated the sport’s fan polls of the 1960s, the popularity of the Funny Car class exploded in the early 1970s, and, unfortunately, so did many of the cars themselves.

Having been transformed from steel-bodied, altered-wheelbase factory cars with engines carrying light loads of nitro into full-on, fiberglass-bodied race cars with loads exceeding 90 percent nitro and filled with engine and drivetrain parts not all used to the stress of several thousand horsepower, the class became a powder keg in the 1972 season with a number of nasty blazes consuming the colorful machines and injuring their drivers. In 1972, the sport’s magazines were filled with stunning images of drivers such as Shirley Muldowney, John "Cogo" Eads, Leroy "Doc" Hales, Jake Johnston, Sammy Miller, Barry "Machine Gun" Kelly, and Ron Fassl riding out flaming top-end barnburners.

When the fiery trend continued into 1973 with high-profile fires at the Gatornationals involving Butch Maas, Jim Nicoll, and Al Bergler -- the popular Maas suffered burns to 50 percent of his body and spent two months in the local hospital burn center -- NHRA took strong action.

Since 1971, Funny Car racers had been required to have 5 pounds of Freon FE-1301 onboard to combat fires. Freon seemed a perfect choice because it was odorless, clear, and nontoxic and extinguished fires by chemical inhibition -- rather than cooling or smothering, it broke the chain reaction of the combustion process. But after the rash of fires in 1972-73, it was clear that something needed to change.

After consulting with SEMA, racers, and manufacturers, within weeks, NHRA had laid out an aggressive plan that quadrupled the amount of fire-extinguishing agent required. Prior to the next event on the schedule, the June Springnationals, all Funny Cars had to be equipped with 20 pounds of Freon or Halon fire-extinguishing agent, divided in such a way that 15 pounds be directed onto the engine compartment by means of an outlet placed in front of each bank of headers and 5 pounds from a separate dedicated bottle to the driver through the means of an atomizing nozzle placed at the driver’s feet.

Also, teams were required to add "fire windows" -- measuring no less than 25 square inches – on the firewall so that a driver could get an early warning that a fire was brewing in the engine compartment. Both of these rules continue to be part of the Rulebook today, though Freon and Halon long ago were replaced by better extinguishing agents, and, as outlined Friday, so much more has been done throughout the years in the form of better safety equipment and better prevention methods.

Another key part of the April 1973 rule announcement was the banishment of the standard open breathers atop the valve covers that often fed fires. Dedicated dump tubes ending in a catch can were now required. The group also recommended better and more encompassing chassis tin to help seal the cockpit from fire.

Former National DRAGSTER Editor and Insider regular Bill Holland wrote two informative pieces in May addressing the problem and offering historic background. He pointed to the 1963 loss of Top Fuel racer and NHRA Division 7 Tech Director Chuck Branham, who succumbed to burn injuries suffered in the Pomona Valley Timing Association’s Starlite dragster. Although firesuits had been in infrequent use for a few years – Holland credited Tommy Dyer, wheelman of the Ansen & Pink dragster, as the first to wear one of Jim Deist’s safety suits – their use was not widespread until NHRA mandated them in 1964, requiring “aluminized, reflective, heat-resistant, and flame-proof suits.” Eventually, NHRA, working with SEMA, developed a specification for these suits, the first known as Spec 3-1 in 1970, that required a suit to withstand 1,750 degrees of heat for a minimum of 10 seconds without the inside temperature reaching more than 250 degrees. Spec 3-2 came two years later and upped the external temperature to 1,850 degrees while lowering the internal requirement to 180 degrees. The spec has been continually upgraded (and the method of measurement changed), but today, Funny Car drivers wear suits designated as Spec 3.2A/20, which are required to have a Thermal Protective Performance (TPP, developed by DuPont in the 1970s) rating of 80 and keep a driver safe from second-degree burns for 40 seconds.

In the wake of all this, two companies – Sperex Corp. (maker of the famous VHT traction compound) and Surface Controls, of Azusa, Calif. – also developed fire-retardant coatings for the fiberglass Funny Car bodies that slowed the burn rate significantly and were tested extensively. Again, today, all Funny Car bodies are required to be coated with an SFI Spec 54.1< flame-retardant covering or coating.

Just prior to the next event on the schedule, NHRA also took delivery of a pair of specially constructed "entry suits" for use by its Safety Safari emergency crews. The suits, built by Filler Safety Equipment to Spec 3-2, would be used to extricate drivers from burning vehicles and to combat fire at close proximity. Specially constructed hoods allowed the wearers to effectively function inside a fire while retaining full vision thanks to lenses made of a space-age material known as Kapton, made of 24-karat gold sandwiched between layers of Mylar, the same design used by astronauts of the era.

The changes resulted in a noticeable drop in the number and severity of Funny Car fires. Of course, there were exceptions (Shirl Greer’s blaze at the 1974 World Finals immediately leaps to mind), but the NHRA’s founding motto – “Dedicated to Safety” – remained a steadfast proclamation that in the decades since has reduced the number of all-engulfing Funny Cars to but a few thanks to the numerous safety improvements and rules I outlined here last week.

On Friday, I'll share the insights of the aforementioned Hales, who used his experience as a medical doctor and former Funny Car racer to help improve driver safety after his driving career ended.

I also mentioned last week the Drag Racing USA magazine Letters to the Editor marathon that got this whole thread about Funny Car fires started. I was pleased to receive from Mark Collins a printed copy of the letter that he wrote to the magazine summarizing the whole thread. You can read it here.