Don't lift until you've heard the referee's whistle

I coached youth hockey for my son’s teams for a number of years, and one of the things I always worked hard to remind the kids of was to keep playing until they heard the referee’s whistle; until then, the puck is live, and play is ongoing. You may think that the puck has been covered by your goalie or that the other team was offside, but assuming that the play is over is one sure way for the puck to end up in your net.

|

The memory comes to mind after writing the Comp eliminator coverage from the recent Mac Tools U.S. Nationals presented by Lucas Oil. In case you don’t follow the Sportsman classes, Jirka Kaplan won the event with his neat supercharged altered, but only after Brian Browell clicked off his D/Dragster before he reached the finish line. Browell had been informed that Kaplan’s car was seriously mechanically wounded – that part was true – but he didn’t know to what extent. Out on his handicap start, Browell heard behind him the roar of Kaplan’s throaty blown Hemi go silent and clicked his machine off early and grabbed a handful of brake to avoid running too far under his class' index and risking a permanent index reduction.

Unfortunately for Browell, Kaplan’s mechanical problem was in the torque converter, and after an initial bog that dropped the rpm from 6,500 to 2,500, he began picking up speed and gaining ground on the unsuspecting Browell and nipped him by 3 feet at the finish line, blasting past Browell’s 125-mph coasting speed at 211 mph.

I watched the race unfold from the media suite behind the starting line and started celebrating in my mind for Browell, a super-nice guy who holds the unusual distinction of winning just three national events, all at the same event, in three straight years (Atlanta, 1999-2001). When Kaplan’s win light winked on, I think we were all floored.

Interestingly, Kaplan’s decision to run his car to the finish line despite Browell rapidly vanishing into the horizon and despite a giant move to the centerline was born out of his own Browell moment earlier this year in the final round at the Mopar Mile-High NHRA Nationals, where, thinking he had a comfortable lead, he chopped the power against Clint Neff, who snuck by him at the stripe. He vowed there and then never to give up a final while the outcome was still in question.

To his credit, Browell, who probably wanted to just keep on driving past the last turnoff road, was honest when asked what happened. He certainly could have fabricated a story about the engine going away or any number of maladies no one could confirm, but he fessed up immediately. When I reached him a few days later, he was a good sport and did an interview with me that concluded simply with, “It was my race to lose, and I did.”

Browell’s type of miscue certainly has been played out many times in many sports. I’ve seen football players streaking for the end zone, ball held aloft in celebration, only to be chased down by a speedy cornerback who strips him of the ball. We’ve seen basketball players not attempt a shot block as time expires, only to watch the winning bucket swish in before their stunned eyes. Like they say, it ain't over 'til it's over.

And, certainly, Browell is not alone in drag racing. For years, the ultimate what-was-he-thinking mantle in drag racing belonged to California Jr. Stock hero Tom Neja, who gave away the 1969 Indy Stock final to Bill Morgan by hitting the brakes on his R/S ’57 Chevy wagon in the lights while holding a substantial lead. Back then, the Stockers didn’t get to pick a dial-under as today but instead ran off of their class’ current national record. Although then a no-breakout rule was in effect in the final that would have allowed him to win the Nationals, running under the national record lowered the record to whatever you ran, making it tougher for you (and everyone else in your class) to run on the record at future events. There was no interview with him after the fact, so we’re only guessing, but it’s a pretty good guess. You can relive that moment of infamy in the video at right by fast-forwarding to the 1:22 mark. (Of course, I know you’re going to watch the whole five-minute video; go ahead. I’ll wait here.) Ironically, Neja was in the same lane as Browell this year.

|

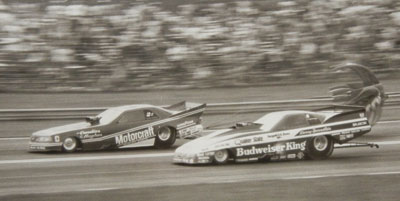

Probably the most infamous incident since then was at the 1987 Summernationals in Englishtown, where Mark Oswald pulled the parachute lever a tad too soon in the Funny Car final against No. 1 qualifier Kenny Bernstein and wound up losing by inches while towing the laundry through the lights. Oswald, at the wheel of the Candies & Hughes Thunderbird, had set low e.t. at 5.52 en route to the final, making him at least a half-tenth favorite against the Bud King, but it all went wrong in the lights. Not only did Oswald lose the race by hitting the silk too soon, but he lost it on a holeshot, 5.56 to 5.53. Double ouch!

“I made a mistake,” Oswald confessed. “I shut it off a little too soon. I saw Kenny in low gear on the first part of the track, and then I lost him. I just lost him, and I felt like I had the race won. It’s just one of those things.”

“I had a crew guy down at the first light, and he said that Oswald was about 3 feet ahead at that point,” said Bernstein. “I saw him most of the way down the track, but about a split second after we hit that light, I remember him disappearing from my view. I knew that I had caught him, but I felt it was too late. I was afraid he had beaten me. [NHRA Safety Safari member] Ronnie Davis came runnin’ up to me and said that I had won. I sort of waved him off, thinking, ‘Come on, don’t kid around with a thing like that.’ But he pointed up at the win lights, and mine was on.”

|

Oswald pretty much had to live with that infamy alone until this year’s Bristol event, where Antron Brown committed the same error in the Top Fuel final against Larry Dixon. Brown got the better light, but Dixon surged ahead early, though it’s clear from looking at the incremental timers that Brown was gobbling up ground. He was 18-hundredths behind him at 330 feet but only two-thousandths back at 660 feet. He pulled the chutes just before the lights and lost by .009-second.

Although losing the final had to be tough, Brown had a very forgiving and consoling crew chief: Oswald. I caught up with the two of them a few weeks later in Norwalk and thought I was going to be Joe Nostalgia Expert by telling Antron about Oswald’s miscue because, surely, not many people could have remembered what happened 24 years earlier, right? Turns out that both of them had been well-reminded about it from fellow racers, fans, and others.

|

The mention of Dixon’s name conveniently brings me full circle back to Indy, where he won his first of four Indy Top Fuel crowns in his rookie season in 1995. He won it due to another premature parachute when Bob Vandergriff Jr.’s chute came out of the pack while he was arguably ahead of Dixon or certainly giving him all he could handle. The bad news for Vandy is that it cost him Indy – his first of 13-and-counting straight final rounds without a win, including in Topeka earlier this year – the good news is that he didn’t pull the chute. Nothing has ever definitively been pinpointed, but Vandergriff once told me that they had been thrashing on the car before the final and that a crewmember had ridden to the staging lanes on the back of the car still working on it and may have partially dislodged the cables. He was pretty far downtrack for tire shake to have been a factor, so it’s anyone’s guess.

And all of this brings to mind something I remember about drivers and parachutes from Hal Higdon's great book on Don Prudhomme, Six Seconds to Glory, which I read when it was exceprted in Super Stock & Drag Illutsrated decades ago. The book included Prudhomme's Funny Car win at the 1973 U.S. Nationals (where he became the first driver to win Indy in both fuel classes) and, as I remember it, focused on Prudhomme's 6.52 to 6.52 semifinal squeaker over Leroy Goldstein (who was driving for Candies & Hughes, making this whole thread kind of a freaky Six Degrees of Oswald Parachute Separation). Prudhomme apparently won the race by inches despite having his chute in full blossom at the finish line. I'm guessing that Higdon asked him about it and got this (paraphrased to the best of my memory) response, "Y'know, it's not the first time I've driven one of the things," and went on to talk about how he knew exactly at what point on the strip he could pull the chute and not have it affect the run, thank you very much, which makes total sense.

Quick Indy quiz: What do drag racing greats Bob Glidden, Ed McCulloch, Gary Beck, Don Schumacher, Raymond Beadle, Dave Schultz, and John Myers have in common? You’ll probably be surprised to realize that – and we’re talking about some pretty special names – all won their first Professional Wally of any kind at the U.S. Nationals.

Rookie Hector Arana Jr. joined the club that actually had 15 members, and, interestingly, opposing him in the final this year was fellow first-year rider Jerry Savoie, meaning that not only for the second straight year were we going to have a first-year bike rider win the Nationals, but that it would be a very special first win (LE Tonglet won it last year en route to the championship, but he had won previously that year).

|

Here’s the chronological roll call: Schumacher (1970, Funny Car), McCulloch (1971, Funny Car), Beck (1972, Top Fuel), Glidden (1973, Pro Stock), Marvin Graham (1974, Top Fuel), Beadle (1975, Funny Car), Gary Burgin (1976, Funny Car), Dennis Baca (1977, Top Fuel), Terry Capp (1980, Top Fuel), Johnny Abbott (1981, Top Fuel), Jim Head (1984, Funny Car), Schultz (1986, Pro Stock Motorcycle), Myers (1989, Pro Stock Motorcycle), Rick Ward (1995, Pro Stock Motorcycle), and Reggie Showers (2003, Pro Stock Motorcycle). Interesting that the last five are bike riders.

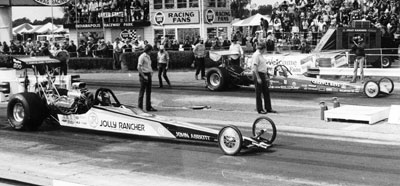

ND staff stats stud Little Bradfield came up with an equally cool stat, uncovering that the Arana-Savoie tilt, guaranteed to produce not only a first-time Indy winner but also a first-time winner period, was the first time that that had happened in Indy since Abbott beat David Pace in the 1981 Top Fuel final. That’s Abbott in the near lane in the Jolly Rancher candies machine and Pace driving for the famed “Texas Whips,” the Carroll brothers.

|

I didn’t know him and, honestly, had never heard of him (what, you expect me to know everything?), but I received three emails this weekend alerting me to the passing of Michigan gasser and street rod legend Al Maynard, who died Friday at age 67, so I find it necessary to share his story with you, thanks to Insider information goldmine Jim Hill, who knew him well.

“I met and became long-term friends with Maynard during my six years working for Holley Carburetor Division, Colt Industries, in Warren, Mich., 1970-76. From day one, Al treated me as a fellow racer and hot rodder. Maynard was an officer in the Michigan Hot Rod Association, the club that presents the annual Detroit Autorama and the Riddler Award. He also served as a judge and was heavily involved in organizing and presenting the event as well as many other MHRA functions. Al was also possessed with an amazingly encyclopedic memory for high-performance-parts options and their factory part numbers, especially those rare 'race-only' options.

“Al's Standard Auto Supply '57 Chevy E/Gasser was well known to NHRA Division 3 Street eliminator and Modified eliminator racers. He held the NHRA class records several times, won class at the Nationals, and was a regular Nationals and Division 3 points-meet participant. He later parked the '57 and built an equally competitive '67 Camaro, also an E/Gas racer.

“Al's black '32 Ford five-window was classic in every sense, homebuilt, a healthy small-block Chevy and four-speed trans. Al lived for many years in Warren and was well-known to hot rodders in the Midwest for his friendly, helpful way. How sad that we've lost yet another of the real good guys in our sport and industry.”

OK, there’s the final whistle on this column. See you later this week.