Greg Anderson continues to pursue perfection in NHRA Pro Stock

Duluth, Minn., is not famous for drag racing. It is famous for hockey, football, and cold weather. That never entered the equation for Greg Anderson, the fastest man to claim the Twin Ports as his hometown. His father raced, sold cars, and eventually got Anderson his first full-time job as a would-be crew chief for John Hagen.

That may surprise those who perceive Anderson as a driver first. Pro Stock has changed dramatically since Bob Glidden and Warren Johnson dominated it seemingly a thousand years ago. Perhaps, it’s not that Anderson is difficult to understand so much as it is that people don’t have the patience to look beyond the red Camaro, and the face that represents so much success.

He is a future Hall of Famer, as if such an indicator matters much in drag racing other than getting invited to give a speech in 20 years. He’s also one of the greatest drivers of all time. That doesn’t seem to mean much either with Anderson, as if we’ve damned him with great praise. How great is he? That’s where the fuzziness sets in.

It can be difficult to know what exactly Anderson does and what he doesn’t do. Some of that is by design in a category that bases some of its sex appeal on secrecy. Glidden throwing his firesuit jacket onto the engine of his wrecked car to protect the secrets of a manifold became an enduring image; it should be noted Jason Line did something very similar less than a year ago in Pomona. Naturally, that came with less fanfare: Motorsports doesn’t believe in recency bias, it believes in nostalgia. Criticize them for their secrecy at your peril. We We claim to want winners in this country more than anywhere else on planet Earth.

We’re founded on winning, we say. We love the taste of glory, we say. But, when K.B. Racing runs the table, we yawn. We don’t bother to appreciate what Anderson, Line, and Rob Downing do to reach the peak of a category that doesn’t have an Everest because the gods of engine development crush mountains only to reshape them taller and steeper than they were before. There are no sherpas — and if there were, could you trust them?

l l l

Anderson became a driver late in a career that nearly didn’t happen to begin with. He worked for Hagen in Minnesota for nearly five years before the regional Pro Stock racer died in a crash at Brainerd International Raceway, the home track for both the racer and Anderson. Clichés do not bring people back and do not assuage the pain of a lost loved one. Hagen died before it was his time, and the impact his passing had on Anderson as someone involved in the sport matters.

“I didn’t even think it was a possibility at the time,” said Anderson. “You look at what the cars were then and what they are now, and that’s really what brought on the advent of the roll cage. We had open-face helmets and all that sh*t at the time … There were a lot of things learned from it, and I guess we just weren’t that sharp at the time.”

That closing, self-effacing jab is common practice for one of the smartest people in the pits, Pro Stock or otherwise. Anderson walks around his red Summit Chevy Camaro to replace spark plugs while he recounts the early days — he has told much of this before — but it’s clear he doesn’t think too much of his natural ability. Anderson’s perspective is simple: He just outworks everyone else. Whether that’s true hardly matters because, think how frightening it is if he’s both better and works harder.

Anderson went back to work with his dad at the family used car lot after Hagen. That could have been the end of his story, and we never would have known what he was capable of at the sport’s highest level. Then he got a call from Warren Johnson, the most dominant racer to ever hail from Minnesota. He wanted Anderson to join his skeleton crew. That meant moving to the south. That meant leaving the used car lot. That meant, in Anderson’s mind, his dad’s business would almost certainly go under.

“I realized my only opportunity to race professionally was to go to the south because you just couldn’t do it in Minnesota,” said Anderson. “I did [have some hesitation], and I kind of left my dad high and dry on the car lot because I did all the repair work and was his right-hand man on the lot. He made it another six months or a year before he shut down. I felt bad about it, but he understood. He loved drag racing and supported me.”

l l l

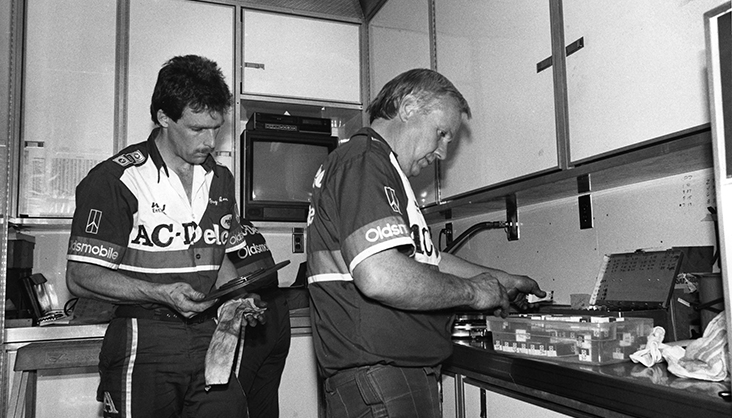

Working with Johnson is not for those that fear hard work. The team was made up of three people: Warren, his son Kurt Johnson, and Anderson. That’s it. It eventually grew to two cars, but it never grew beyond three full-time team members. There was no engine shop. There were no full-time members working nine-to-five (or longer) days while the team toured the country to race. There was Warren. There was Kurt. There was Greg.

When Kurt began racing full-time, Anderson earned the title of crew chief. It feels insulting to dissect that, but it appears there has never been a time when “crew chief” meant one thing to everyone. It has always been a term bandied about like so much tire smoke to fit the needs of the team at hand. So, instead of relying on terminology that doesn’t mean the same thing to anyone, let’s talk about what Anderson did for Johnson.

“[Johnson] knows a lot about everything, but he wasn’t really a car guy; he was an engine guy,” said Anderson. “He thought he could do everything; he thought he could tune the race car, and he struggled with that. If you remember those days, Warren struggled to make consistent, quality runs. That was his downfall. When he did run, he was very fast, but he shook the tires a lot.

“We kind of figured out the whole package where we eventually separated. I was working on the car stuff, and he was working on the engines. To this day, he’ll tell you he can do everything, and I’ll tell you right now: Nobody can do everything. He kind of got left behind with that mentality.”

That situation is flipped from what Anderson does now. Line is known as the engine guy at K.B. Racing, but Anderson has worked on the engines since bringing Line on nearly two decades ago. Raising eyebrows at Anderson’s title with Johnson because of who he worked with is to misunderstand what Anderson is capable of.

l l l

You may have noted Anderson did not speak of his former employer in glowing terms. He didn’t spend a moment dragging Johnson’s name through the mud, either, but Anderson is realistic about the friction that has existed between the two since they split in 1998. Anderson wanted to drive. Johnson said when he stepped away from the car, a seat would be made available. Eventually, Anderson got tired of waiting.

He drove for three years before the formation of K.B. Racing. That started as a two-car team with himself and Line as drivers. Anderson did not have a Pro Stock win at this point, and, as a 49-year-old, he wasn’t setting his sights on passing by NHRA Drag Racing legends when Ken Black offered him the opportunity to create a juggernaut. He took what he learned from his already long career, put his solid financial backing to good use, and got to work.

“When I went my own way, I hired people that were good with engines,” said Anderson. “Since then, I’ve learned as much as I could about them. So, for the past 20 years, I’ve been working on engines. I guess I have two chapters in my life: A car guy and an engine guy.”

It’s not exactly Nick Fury calling The Avengers to assemble (no eye patch, for one), but Anderson emphasized the biggest lesson he learned from Johnson: Know your shortcomings and hire people who can fill the gaps. Hiring Dave Connolly over the offseason from the now disbanded Gray Motorsports Pro Stock team is an example the veteran hasn’t forgotten that lesson.

l l l

“If you go out and win 10 races in a row, people are going to say, ‘man, he must be a really good driver,’” said Anderson. “And to be honest, the motor made you a great driver; it goes hand in hand. In NASCAR, if Kyle Busch’s motor is a piece of sh*t, he doesn’t look like that great of a driver. Now, he’s the best driver out there, but with a sh*t car, he doesn’t look like anything special.”

Anderson knows the car he brings to the starting line determines his odds of winning every weekend. An informal poll presented Anderson as the most competitive racer in the category; so how does someone who hates losing stay sharp at the starting line in lean years? He says working on the engine, the difference between winning or losing, offers some solace.

“Those special years where we were dominant before the competition catches up or passes us by, those types of years are the motivation for us right now,” said Anderson. “You go back to the shop every single day looking for more power and looking to get back to dominance. That’s what everyone says the sport doesn’t want or doesn’t need, but that’s our job. That’s what we are supposed to do.

“We’re supposed to find a way to dominate and win races. That’s what your best Top Fuel racers are trying to do, that’s what your best Funny Car racers are trying to do, and that’s what your best racers in this group are trying to do. You think Richard Freeman and his group aren’t trying to do the same thing? You’re damn right they are. The engine gives you the key to that opportunity.”

Anderson was a top-three driver in reaction-time average when he won the 2010 Pro Stock championship. His average has hardly wavered since that time, but the class has become more cutthroat. Erica Enders, Deric Kramer, and most recently Tanner Gray raised the stakes in a category that’s always been the driver’s class in NHRA Drag Racing. He doesn’t need to be asked about his future; it’s on his mind.

“I know that I’m, whatever the hell I am, 58 years old, and it may be six months from now, it may be a year from now, and it might be three years from now, I don’t know, but at some point, I’m not going to be able to do what these young kids can do out there,” he said. “When I can’t cut lights consistently and can’t win out there anymore, I won’t be out there anymore. I’m not going to be like Warren; I’m not going to keep going to the damn races if I don’t have a chance at winning. I don’t think I’m there yet, but it could be soon, I don’t know.”

He has 92 career victories, all in Pro Stock, only five behind Johnson. Reaching 98 would make him the all-time leader in the category and the fifth-winningest driver in NHRA Drag Racing history. That’s so far beyond what the 10-year-old from Duluth, carrying buckets of water for his dad in the staging lanes, could have possibly imagined.

His singular commitment to dominance is rare in any sport and difficult to grasp while it’s happening right in front of your face. Anderson doesn’t represent a dying breed, nor a man out of time. He is a dominant force that continues to put on a show, whether anyone chooses to appreciate it or not. For your sake, it might be worth tuning in.