'Jungle Clare' Sanders

|

| Clare Sanders, then and now |

|

By 1969, the Funny Car class was in full bloom and contested at three NHRA national events. After its debut at the 1966 World Finals, the fledgling class was showcased in 1967 at the Springnationals in Bristol, Tenn., and the U.S. Nationals, which were won, respectively, by Tommy Grove and Doug Thorley. NHRA held no Funny Car races in 1968 but returned with three in 1969: the Winternationals, Springnationals, and U.S. Nationals. The latter two were both won by Danny Ongais in Mickey Thompson’s Mach I, but the 1969 season opener was won by 27-year-old Clare Sanders, at the wheel of “Jungle Jim” Liberman’s Chevy II.

Sanders, now 74, and the beautifully restored flopper were both at this year’s Circle K NHRA Winternationals as part of NHRA’s 50 years of Funny Car celebration. Sanders was warmly greeted by SoCal’s famously nostalgic fans and took part in a panel discussion Saturday with fellow former flopper pilots Don Prudhomme, Kenny Bernstein, Ed McCulloch, Al Segrini, and Tom Prock. I caught up with him earlier this week to reminisce about his turn in the Pomona spotlight.

It was a long road to the Pomona winner’s circle from Sanders’ childhood in Alaska, where his father was in civil service and the military. His family later moved to the lower 48, and it was in Washington where Sanders began racing in 1960, partnering with mechanic Jim St. Clair on a number of cars while he was attending college in Idaho. When the Christmas Tree began replacing the flag starter, Sanders became especially adept at matching the rhythm of the five-bulb countdown and gained a reputation as a “leaver.”

Sanders and St. Clair moved to San Jose, Calif., and the hotbed of Northern California racing in 1963-64. Fate smiled on the duo when St. Clair met Jack Groner, a retired businessman looking for “a little excitement” in his life. Groner had a thick wallet and Sanders and St. Clair a head full of dreams; it was the perfect match. Interestingly, their first endeavor as J&J Enterprises in 1965 was not a race car but a liquid traction compound for drag racing that replaced the arduous task of applying and “brooming in” powdered wood rosin to the track surface. St. Clair came up with the mix, which combined a synthetic rosin, methyl isobutyl ketone, and toluene. Groner figured out how to mix it all together, and Sanders, who also had some knowledge of chemistry, came up with the very ‘60s name: “Boss Bite.”

“It was the first of its kind and really popular, especially for the first injected Funny Car-style of cars that had a lot more power than the tracks could handle,” recalls Sanders. “We’d either spray the track or the drivers would paint it onto their tires. It was very popular, and the company became very successful; the money was really rolling in. We had a big bank account and sat down one day and said, ‘Well, do we want to keep building Boss Bite or do we want to go racing?’ We all voted to go racing. We cashed everything in and went racing.”

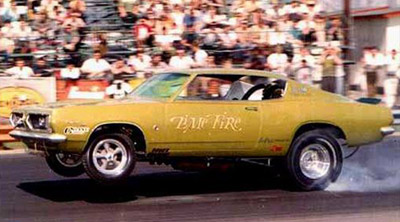

Their first car, dubbed Lime Fire for its factory-paint color, was a huge hit. Built to stock dimensions and retaining somewhat of a street-car resemblance – down to the real chrome trim – as desired by money man Groner, the Barracuda was once called “The World’s Most Beautiful Funny Car." Using the popular Logghe chassis as inspiration, they built their own chassis and fitted it with a 392 Chrysler backed to a Torqueflite transmission. The show-car-worthy entry, towed to the races behind Groner’s Cadillac, not only won in its debut at an NHRA divisional meet at Southern California’s Carlsbad Raceway – running in Super eliminator because Funny Car was still not widely accepted as a class unto itself – but also caught the eye of Hot Rod magazine photographers at the event, who featured the car in their December 1967 issue, further gaining them popularity and bookings.

|

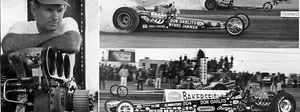

| Jim Liberman, and Brutus, 1965; he was barely out of his teens. |

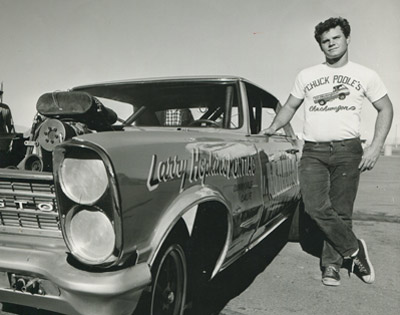

The trio had been sharing shop space with Funny Car pioneer Lew Arrington and his new driver, a kid named Russell James Liberman, a transplanted Pennsylvania-born high school dropout who was building headers at Goodie’s Speed Shop in San Jose. Despite being barely out of his teens, Liberman already was driving wild cars like the injected-nitro Hercules Nova, Arrington’s blown-on-nitro Brutus GTO, and, ultimately, his own Goodies-sponsored Chevy II, in which he earned his memorable “Jungle Jim” nickname for his wild, on-track performances. They all became fast friends, and when the Lime Fire was ready, they toured together, along with NorCal-based Don Williamson and his Hairy Canary Plymouth Valiant.

“ ‘Jungle’ was always a little ahead of us; he was a sharp guy,” Sanders recalled fondly. “He was a racer, 100 percent; you could tell it and feel it. He was good in the car and good at getting sponsors. He did all of the things that we all tried to emulate. As much as he’s known for his showmanship, in my opinion, what he did best was win races.”

The Lime Fire ran hard – at one pointing posting a 7.71 at Orange County Int’l Raceway, at the time the quickest pass in class history, according to Sanders – and scored a runner-up at the 1968 AHRA Winternationals at Beeline Dragway outside of Phoenix, finishing second after losing the driveshaft in the final against Eddie Schartman. By late 1968, the thin-tube Lime Fire chassis, built for speed and not the long-haul grind of match racing, was on its last legs, and Liberman, with his popularity growing virtually by the week, decided to add a second car – pretty much unprecedented at the time – to keep up with match race demand. He looked no further than his traveling buddy Sanders, who wasted no time in accepting the offer.

“I worked on Jim’s crew while the second car was being built, and we were at a match race in Suffolk, Va., one night, and he caught me totally off guard when he said, ‘You know, I’ve never seen my car make a run. Why don’t you drive it tonight?’ I put on my firesuit with his helmet goggles, and we beat Malcolm Durham that evening with a new track record,” Sanders recalled.

The new car, with a Logghe chassis, Fiberglass Ltd. Chevy II body, and supercharged 427 Chevy power, was a twin to Liberman’s car, with the exception of an inch-and-a-half engine setback for better traction on the more marginal tracks on Sanders’ match race docket. Sponsorship was provided by Philadelphia speed shop entrepreneur Steve Kanuika.

“Compared to the Lime Fire, ‘Jungle’s’ car was a dream to drive,” he recalled. “My first race for ‘Jungle’ was in late 1968 against Don Nicholson at Delmar, Del. The car was still just painted white pearl, which we sprayed on the car before the candy blue, and we split the first two rounds. In the final, we both ran 7.86, and I beat him on a holeshot. That was a good start.”

The team’s first major outing together was the 1969 AHRA Winternationals. An anecdotal story is floating around about the two running one another in the semifinals, with Liberman winning but turning the car over to Sanders to run the final against Dickie Harrell, but Sanders says that never happened. “We never swapped cars in the middle of a race,” he insists. “Sometimes, but not often, we’d trade cars before a race, but never in the middle.”

All of this preamble, of course, leads to the NHRA Winternationals in Pomona and the official West Coast debut of the Funny Car class. The racers turned out by the dozens, with 40 or more cars trying out for the 16-car field. (“Everyone was there,” marveled Sanders. “It was like walking into Carnegie Hall.”) Traction was a little tricky because, due to weather/time concerns, the Funny Cars were not allowed to burn out across the starting line as they were at match races, and Liberman did not qualify for the field. Sanders’ car, however, qualified an impressive No. 3 in a talent-laden field, but everyone was well behind Tom McEwen’s direct-drive Tirend Activity Booster Barracuda, powered by a Tim Beebe-prepped 392 Chrysler. (Beebe would have more reasons to celebrate at the event: He and partner/driver John Mulligan won in Top Fuel.)

| 1969 WINTERNATIONALS FUNNY CAR FIELD | ||

| Tom McEwen | 7.796, 193.66 |

Low qualifier Tom McEwen

|

| Don Schumacher | 8.024, 193.65 | |

| Clare Sanders | 8.035, 191.08 | |

| Ray Alley | 8.148, 183.67 | |

| Randy Walls | 8.204, 180.00 | |

| Rich Siroonian | 8.223, 185.11 | |

| Pat Foster | 8.240, 181.45 | |

| Mike Hamby | 8.256, 187.89 | |

| Marv Eldridge | 8.277, 185.95 |

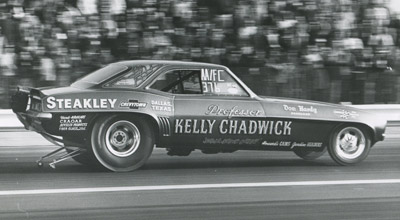

Kelly Chadwick

|

| Dave Beebe | 8.277, 188.28 | |

| Kelly Chadwick | 8.298, 187.89 | |

| Art Ward | 8.300, 185.56 | |

| Leonard Hughes | 8.311, 187.89 | |

| Eddie Schartman | 8.326, 174.75 | |

| Ron Leslie | 8.326, 170.13 | |

| Larry Reyes | 8.331, 180.72 | |

Among those joining Liberman on the sidelines were hitters like Ongais, Nicholson, Roger Lindamood, Jack Chrisman, Charlie Allen, and Della Woods.

Liberman’s DNQ proved a boon to Sanders, as “Jungle” was able to apply his tuning magic to the Chevy, which came to life in eliminations, and when McEwen surprisingly blew his engine in a round-one loss to Marv Eldridge’s Fiberglass Trends AMX, he and Leonard Hughes became the favorites.

|

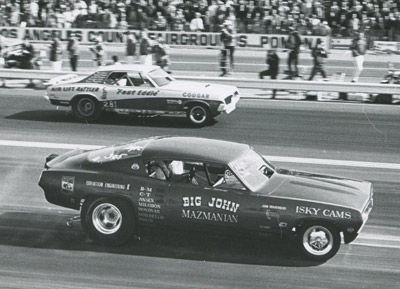

| Round one: Rich Siroonian holeshots "Fast Eddie" Schartman |

|

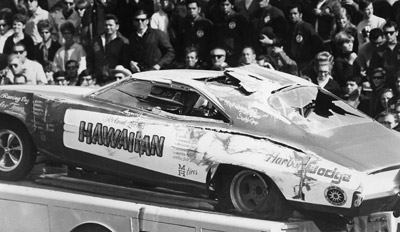

| The flyin' Hawaiian |

Hughes and the unlettered Candies & Hughes Barracuda steamed to low e.t. of the first round with an 8.01 to beat Randy Walls’ 8.22 while Sanders was right there with an 8.09 over “Professor” Kelly Chadwick’s 8.53.

The rest of the round went like this: Rich Siroonian slapped a holeshot on Schartman and his SOHC-powered Air Lift Rattler Cougar, and even “Fast Eddie’s” 8.39 couldn’t catch “Big John” Mazmanian’s candy-apple 'Cuda’s 8.45. Art Ward lost traction in Roger Guzman’s Assassination Too Corvair, falling to Ray Alley’s 8.41 in the Engine Masters Barracuda. Ron Leslie’s High Country Cougar ran 8.17 to defeat Pat Foster in Mickey Thompson’s other Mustang in a battle of SOHC-powered machines. Dave Beebe smoked hard in Nelson Carter’s Super Chief Charger against Don Schumacher’s 8.24. The round’s most spectacular moment came at the conclusion of Larry Reyes’ 8.14, 181.45-mph victory over Mike Hamby when his Roland Leong-owned Hawaiian Charger took flight in the lights and soared 200 feet before crashing back to earth.

Hughes looked unbeatable again in round two with a 7.86 at a sizzling 198.23 mph (top speed of the meet) to beat Eldridge’s 8.35. Alley took an 8.32 bye run in the Hawaiian’s absence, and Siroonian eked out a win over Schumacher’s John Hogan-tuned Stardust Barracuda, 8.10 to 8.12. Sanders, meanwhile, threw his hat further into the ring of contention with a 7.88 at 181.08 that dispatched Leslie’s early-shutoff pass.

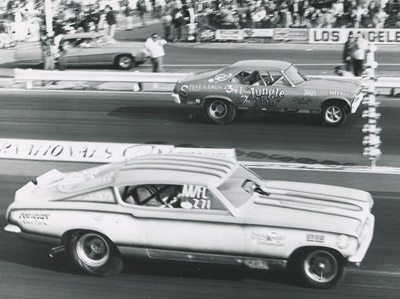

(Above) Sanders beat Leonard Hughes and the Candies & Hughes 'Cuda in the semi's and Ray Alley's Engine Masters Dodge in the final (below).

Sanders is flanked in the Pomona winner's circle by mechanic Carl Dubow, race queen Marsha Bennett, and Bobbie and Jim Liberman.

All eyes were on Sanders and Hughes in the semifinal clash of 7.8-second cars, but Hughes – who had grenaded his best engine in qualifying – lost another engine early and watched Sanders soar into the final with low e.t. of eliminations, 7.80, despite “tuliping” an exhaust valve (common for those early nitro Chevys), which necessitated a between-rounds cylinder-head swap. Alley joined Sanders in the final, earning a white-knuckle 8.270 to 8.271 victory over Siroonian.

With the eyes of the sport – not to mention the Wide World of Sports cameras – looking on, Sanders suited up for the final he was expected to win. He liked to get into the car early to calm the butterflies and get mentally right, and “Jungle” leaned in and told him not to change a thing that he had been doing all day.

The final proved pretty lopsided as Sanders got the win light and the $5,000 payday with a 7.88 at 187.89 over Alley’s 8.11, 187.11.

“It was pretty surreal to get out at the other end, and there’s [ABC’s] Keith Jackson and the cameras,” he said. “The funny thing though was Keith walked up to me and said, ‘Congratulations Jim Liberman on winning the Winternationals.’ People were used to just seeing one ‘Jungle’ car, and I was relatively unknown at the time, so I understand why he was confused. I was so happy, I didn’t care, but he was nice enough to reshoot it for the show [which ran the following weekend].

“The next day, a couple of us went to Disneyland to celebrate, but ‘Jungle’ got on the phone and booked both cars for the rest of the year. We were out and having fun, and he was working; that’s the way he was.”

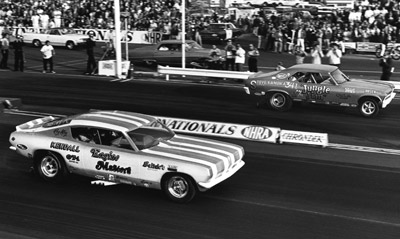

Liberman hired Larry Petrich as crew chief for Sanders for the rest of the year, with a number of highlights. On the same night, both Sanders and Liberman won “Mr. Chevrolet” races at U.S. 30 Dragway and Capitol Raceway, respectively. Sanders then went off to Kansas City, Mo., where he beat “Mr. Chevrolet” himself, Dickie Harrell, on his home turf. Fans seldom got to see both “Jungle” cars at the same track on the same date, so much in demand was the “Jungle Jim” name. And although Sanders admits there were times when fans came to a track expecting to see Liberman instead of him, eventually, he developed his own strong following. Throughout the summer, both cars ran pretty much every other day, and, according to Sanders’ logbook, they won 86 percent of their races.

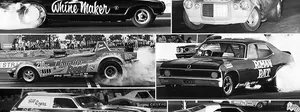

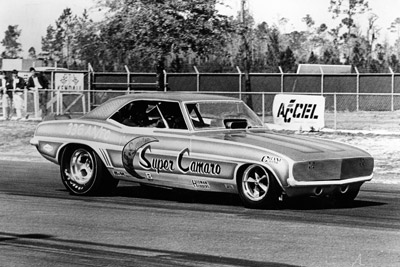

The Super Camaro

Sanders also wheeled the famed Chi-Town Hustler

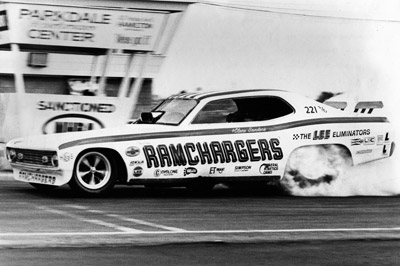

The Ramchagers Dodge was Sanders' last ride

Without putting too much of a fine point on it, Liberman’s personal life changed pretty significantly late in the 1969 season, the team dynamics changed, and Sanders decided it was time to move on. He partnered in 1970 with New Orleans-based Frank Huff on the Chevy-powered Super Camaro (and, later, Super Vega).

“We had a lot of bookings with that car, and it paid real well, but by the end of the year, the tires had gotten a lot better, and the Hemis were just running away from the Chevys,” said Sanders, who was about to get another major career boost. “Austin Coil came over to me one weekend and told me that Pat Minick was going to stop driving the Chi-Town Hustler, and they were looking for a replacement. ‘Are you tired yet of driving this Chevy?’ he asked me. ‘Well, yes I am,’ so I went to work for them. I was a lot smaller than Pat and had to put pillows in the seat, but that was a great car. It was like driving a Buick. It was a big, huge race car.”

)He thinks he got Coil’s attention when he filled in for Schumacher at a race at New England Dragway and quickly mastered the new clutch combo in the car; at this point, most cars still had an automatic transmission with a footbrake, and Schumacher’s car had the now-familiar hand brake. It also was the first car that Sanders had driven that had a butterfly steering wheel.)

After finishing 1971 with the Chi-Town team, Sanders got the call from Ramchargers President and crew chief Pete Goulet to drive their famed car, which in 1970 had broken the six-second barrier with Leroy Goldstein at the wheel. Goldstein had moved on to drive for Candies & Hughes and been replaced by Arnie Behling, who didn’t work out. Sanders helped the team sort through some handling issues, and the car became a real runner again, dominating the 1972 IHRA Summernationals and setting the IHRA national record.

Sanders drove for the team for a year and a half before it dissolved as factory backing began to dry up across the class. Looking for steady employment and a future beyond drag racing, Sanders went to work for Snap-on Tools driving a truck and in a 30-year career worked his way into management and sales. The experience he gained there led to his post-retirement gig, building websites for the likes of Don Garlits, Tommy Ivo, and a bunch of his old racing buddies.

Sanders’ driving career only lasted about six years, but he packed a lot into that short span, winning national events and driving for three of the sport’s iconic teams. Does he have any regrets about not staying behind the wheel?

“Pretty much every day,” he answered with a laugh. “The first couple of years after I quit were an adjustment, but it’s very rewarding to know people still remember me. The reception I got at the Winternationals was phenomenal. A lot of people came up to tell me they were there when I won. It was very gratifying.”

You can check out more on Sanders, his career, and his cars at his website, www.claresanders.com.