'Fast Eddie' Schartman

We began this whole odyssey into the early days of Funny Car with the announcement a few weeks ago that NHRA would be saluting 50 years of Funny Cars this season, with the starting point for the celebration being the 1966 season, when NHRA handed out its first Funny Car eliminator trophy to Eddie Schartman and his Ohio-based Mercury Comet at the 1966 World Finals in Tulsa, Okla.

As we have discussed the last few weeks, the roots of the class are well-defined in general yet somewhat murky in absolutes, so it’s time to bring it all back to that 1966 season, where some better clarity exists, and who better to help than “Fast Eddie” himself?

I caught up with lifelong Ohioan Schartman, now 78, earlier this week at his winter home in Florida to talk about those early days of the class and his involvement in it.

First, a little background. Schartman, who was inducted into the International Drag Racing Hall of Fame in 2012, actually grew up in a dirt-track-racing family, where his father, Ed Sr., was a regular competitor. Being around racing instilled in young Eddie a love not only of racing but also of all things mechanical, and because the family owned a wrecking yard, he got plenty of hands-on experience at tearing apart cars. In school, he devoured the lessons from every shop class he took, all aimed at achieving his ultimate goal of becoming a racer.

He built his first drag car, a flathead-powered '40 Ford, when he was 14. By the time he graduated from Berea High School in 1956, he was already a skilled racer. He journeyed from Cleveland to Flagler Beach, Fla., for Daytona Speed Week in a street-driven ’56 Chevy with a stroked-out 338-cid engine and won everything in sight, and shortly afterward, he set the NHRA B/Gas record with a full-race ‘55 Chevy.

Schartman went to work for the Cleveland-based Jackshaw Chevrolet dealership, which had a pretty good pipeline to Chevy high-performance parts and was frequented by Chevy’s biggest doorslammer star, “Dyno Don” Nicholson. Schartman was running a ‘62 Chevy out of the dealership that regularly sent the local Ford drivers packing, and the two became friends, which led to a job offer from Nicholson, who asked Schartman to move to Atlanta and build engines for him in 1964.

Soon, Nicholson got a Mercury factory deal and a new A/FX Comet station wagon known lovingly but unflatteringly as “The Ugly Duckling.” Schartman took over the wheel of Nicholson's '62 Chevy – for 50 percent of the winnings – and made a killing down South.

Nicholson’s new bosses at Mercury, however, did not appreciate still seeing his name on a Chevrolet, so when Nicholson got a new Comet coupe in 1965, Schartman got the Comet wagon. Schartman claimed the Mr. Stock Eliminator win at the 1965 NASCAR Winter Drags, but he had grown tired of working for someone else and handing over half of his winnings, and his relationship with Nicholson had become quite rocky. Mercury so valued its young racer that when he demanded his own car, it gave him a Comet – and a lucrative (for the time) $5,000 sponsorship from the Cleveland-area Mercury dealers – albeit with a wedge motor instead of the cammers bestowed upon others on the factory deal to finish 1965.

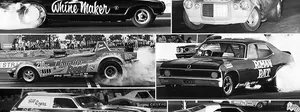

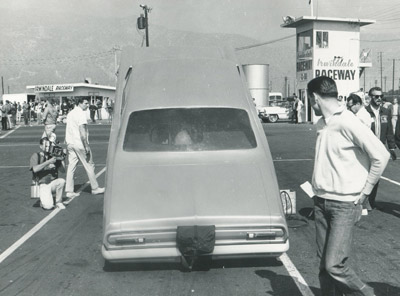

(Above) Don Nicholson's Comet at the 1965 Winternationals with stock wheelbase and (below) after his alterations. Notice how the word "Comet" had to be made smaller to accommodate the elongated wheelwells.

Nicholson's flip-top car got a lot of double takes in its debut at Irwindale Raceway in early 1966 at the AHRA Winternationals, but you had to look fast. The car lost its body on its maiden pass (below).

The bodyless chassis gave a good look at the coil-over shocks and injected engine.

While all of this was going on for Schartman, his bosses at Mercury had bigger fish to fry. When the Dodge and Plymouth racers began showing up in 1965 with radical altered-wheelbase cars, their better weight distribution and acid-dipped, anything-goes bodies gave them a huge advantage over cars like Nicholson’s Comet, so Nicholson followed suit, offsetting his chassis and adding an 18-percent engine setback, but when his bosses at Mercury saw it, they were not pleased, to say the least, and by some accounts were ready to wash their hands of this whole drag racing business.

Fortunately, Mercury Racing boss Fran Hernandez and right-hand-man Al Turner were there to save the day and, in the process, show the way forward for the class. According to most, Hernandez had his hands full with other factory programs, and it was Turner, a longtime gas dragster racer who also ran a machine shop at night to fund his own racing efforts, who took the football and ran with it.

Knowing that a car that didn’t reasonably resemble a street car would never pass muster, Turner found inspiration in the famed Mooneyham & Sharp 554 Ford of Gene Mooneyham and Al Sharp. Externally, the car looked like a pretty stock ’34 Ford coupe, but beneath the body was a tube chassis with a center-mounted driver position and a blown nitro Hemi whose injectors were barely visible at the base of the windshield.

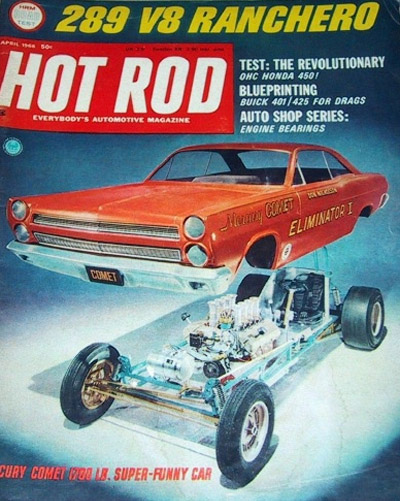

Turner went as far as to build a 1/25th-scale model out of balsa wood to show his bosses for approval – touting especially its stock appearance – and received their blessing. He looked homeward, calling on brothers Ron and Gene Logghe – whose Detroit-area Logghe Stamping Co. had begun to make a name for itself with dragster chassis – to build the chromoly frame with a stock 116-inch wheelbase and stock proportions. Multiadjustable shock absorbers were added in what Turner said was the first use of coil-over shocks on a drag car. The Logghes were sworn not only to secrecy but also had to agree not to make a similar chassis available to other racers for one year.

Turner worked with the Ford design studio to create a clay buck of a ’66 Comet body, which was then delivered to Plastigage Custom Fabrication of Jackson, Mich. The first bodies were incredibly heavy – the target weight was 250 pounds – and were rejected and had to be remade. Still, even with a Plexiglas windshield, they were prohibitively heavy because the original design called for the bodies to be bolted to the chassis and then lifted off for between-rounds servicing. According to Gene Logghe’s son, John, it was his uncle Ron who came up with the idea of hinging the body in the back, creating the “flopper” as we know it today. Drag racing’s “Tin Man,” Al Bergler, fabricated the aluminum floor, firewalls, wheelwells, and interior panels.

The Ford 427 SOHC cammer engine had low-stack Hilborn injectors that hid nicely beneath the body (the cars would not be supercharged until 1967). The cammer was mated to a three-speed manual transmission for its initial passes in South Florida in late 1965, but Nicholson was having problems hitting the shift points and kept overrevving the engine, so an automatic transmission with a 4,000-rpm stall torque converter was substituted. The Logghe brothers later created a ratchet shifter that made things even easier.

The flip-top Comet’s debut, at the AHRA Winternationals at Southern California’s Irwindale Raceway, was memorable but for the wrong reasons. The front grille caved in on the car’s maiden voyage, triggering the body latch and sending the Comet body soaring into the SoCal sky. Hayden Proffitt, another of Mercury’s California aces, helped Turner load the remains onto his flatbed truck and burn it to keep it from falling into the hands of the competition.

The next edition of the body (with the latch now reversed) was sent through the Ford wind tunnel, which highlighted the need for a spoiler beneath the front bumper, which solved the problem, and Nicholson went on to great success with the car, but without incident, as he also flipped the second car while match racing back east.

Jack Chrisman also got one of the new cars (though his was a "convertible" version, which later burned to the ground), as did the Colorado-based Kenz & Leslie team (who also kited one of their early cars), and, of course, Schartman.

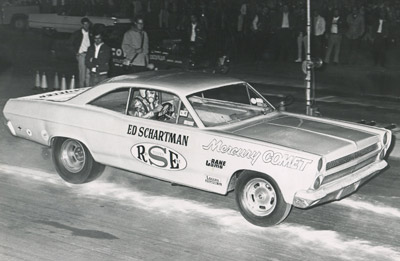

The Schartman-Nicholson rivalry was intense in 1966 and 1967. (Above) "Fast Eddie" beat "Dyno Don" at the 1966 World Finals to claim NHRA's first Funny Car win.

Schartman will never forget the first ride in his new flip-top Comet, in December 1965 at Motor City Dragway. Turner had called him to the track, telling him only that his new car for 1966 was ready.

“I walked in there, looked at the car, and said, ‘What the hell is this?’ " he recalled. “It was a dragster with a body on it and the driver in the back seat and not the front seat, where you belong. I told them, ‘I can’t drive something like that.’ My car would run 125 [mph], but these things would do more than 160. He just said, ‘Well, that’s your baby. Get in.’ They were a handful; they never wanted to go straight. On my first pass, I went 166 mph and took out the [finish-line] lights. It took me several runs to get the hang of it, and, like any drag racer back then, you got used to the speed and loved it. Those cars weren’t like anything else out there, and once we got out there, the demand from the tracks and fans to see those cars was incredible. The phone was always ringing off the hook.”

Mercury had hired nitro-tuning veteran Roy Steffey to help Schartman in 1966, but it wasn’t a partnership that lasted long due to – how shall I say it politely? – “philosophical differences.” Schartman ran 80 to 85 match race dates a year – he also made innumerable appearances at car shows and Boy Scout events on behalf of Mercury – beginning in the West in the winter, then concentrating on the Midwest and East Coast, winning everywhere he went, with Nicholson as his only real consistent threat in the performance department.

“We were definitely one another’s main competition, and unless we blew something up, there was a good chance we were going to win,” he said modestly. “Everyone was hand-grenading their engines trying to beat us because that was a big deal, but you also have to remember that we were running stock 427 blocks, too, that could only stand so much before blowing the crank out of the bottom. I knew just how much nitro I could put in there and keep the motor together, but if I had to put in over 90 percent, I was probably going to lose the motor.”

The 1966 NHRA Nationals featured dedicated classes for “funny cars” running in S/XS, A/XS, and B/XS. Schartman and his yellow RSE (Roy Steffey Enterprises) Mercury clinched the S/XS trophy with an 8.28 at 174.41 mph over Nicholson.

More than a month later, at the 1966 World Finals, the two types of Funny Cars were divided, with A/XS and B/XS running in a class known as Handicap Experimental Stock and S/XS cars running in a class designated then as Top Funny Car. Among those in competition against Schartman were Nicholson, Chrisman, Larry Reyes in the Kingfish, Maynard Rupp in his wild Gratiot Auto Supply Chevoom Chevelle, and the Kenz & Leslie Mercury. Again, Schartman trumped all, and again he defeated Nicholson for the money, running an 8.38 at 174.08 after Nicholson was forced to abort his run.

Gene Snow’s Rambunctious Dodge Dart, which had won in Comp in Indy running in the C/Fuel dragster class, won the X/S combo over Hubert Platt, who red-lighted in Dick Brannon’s Mustang, which gave Snow the right to meet Schartman in Sunday’s overall match. Snow, who was running considerably slower than Schartman on Saturday, red-lighted trying to make up the disadvantage.

Knowing that blowers were the next big thing, Schartman, who usually wintered in California with Chrisman, hired supercharger-savvy Californian “Famous Amos” Satterlee as his crew chief for 1967. He signed a major sponsorship deal with Air Lift and grabbed another piece of Funny Car history when he made what was said to be the first seven-second run in a stock-bodied car in April at Detroit Dragway. (Nicholson also reportedly laid claim to a similar accomplishment, and Schartman acknowledges that timing systems back then weren’t all that they are today and doesn’t put a lot of stock in those kind of "firsts.")

“I think it was a big deal in those days, especially for the factory guys,” Schartman said. “The bosses would say, ‘Schartman went this e.t., “Dyno,” you’d better get your ass in gear or you won’t get the good parts,’ but we were very competitive with each other those years.

“I remember in 1967, we were running Maple Grove [Raceway], and the car was going sideways in the lights because the back end was almost coming off the ground. We figured we had to get some weight on the back end, so one of the guys went to a hardware store and came back with some angle iron that we bolted onto the trunk of the car. It went straight and picked up 5 mph. We’d invented the [rear-deck] spoiler and didn’t even know it. We were going 190, and ‘Dyno’ was still in the 180s, and believe me, he heard about it.”

Schartman went on to win Orange County Int’l Raceway’s prestigious Manufacturers Funny Car Championship that year and also won Irwindale’s Grand Prix and Fremont Dragway’s Northern California Championship.

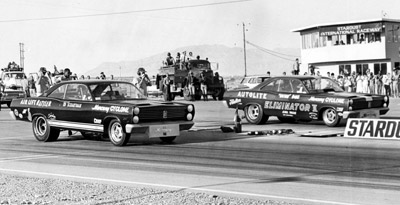

Major wins in 1968 with the Air Lift Rattler Cougar – which had a pedestal-style rear spoiler – included the AHRA Winternationals and Great Lakes Dragaway’s Night FC Championships, and he posted a runner-up behind Nicholson at the Stardust National Open.

As the speeds increased in the class, so did the accidents and fatalities, especially because anyone could buy a Funny Car chassis. Mercury and Ford, which had merged their racing efforts by this time, informed the factory teams late in 1968 that they were dropping their backing of the Funny Car class. Schartman, who already had sponsor and match race commitments for 1969 for two cars – with Arnie Behling in his ‘68 car – worked out a low-six-figure settlement that allowed him to run the 1969 season.

Schartman was part of the inaugural Winternationals Funny Car field in 1969 with an 8.32 and lost on a holeshot to Rich Siroonian, 8.45 to 8.39, in the first round. Although he was still tearing up the match race scene, he also lost in the first round at the Springnationals and the U.S. Nationals. After fouling against Bruce Larson in Indy, he finished the year with some match racing, then retired from the class.

Pro Stock was new to drag racing in 1970 and was a good fit for both Schartman and Nicholson. Schartman started the season with a Boss 429-powered Cougar but soon switched to a Maverick.

So used to winning in Funny Car, Schartman experienced little more than frustration in national event Pro Stock racing, finding the sledding tough against guys like Bill Jenkins, Ronnie Sox, and Bob Glidden. A low point certainly was his disqualification in tech at the 1972 Gatornationals, where his Ford Maverick was not allowed to run in Pro Stock because it had Mercury Comet taillights in it – same parent company, but not the same make. He was allowed to run in B/Gas in Modified eliminator and nearly rode the karma train to victory, losing only in the final round to Dennis Grove.

“The Modified guys were mad because they had to run a ‘professional’ driver, and I just began getting so many bad vibes about the whole Pro Stock thing that I decided I couldn’t run the national events anymore,” he said. “I just started running match races, but even that went bad in 1975 when I started getting rained out so much at match races. The rainout money was like $150, and I just couldn’t afford to do it anymore."

Schartman left racing but not cars, buying and selling cars wholesale, which led to the purchase of multiple dealerships and, later, NAPA Auto Parts stores.

Now retired from business and playing golf every day, Schartman looks back fondly and proudly on his years in the sport.

“We lived and died racing,” he said. “We didn’t do anything but work on our cars and find a place to go racing. It was a great life and left me with a lot of good memories.”