The Top 20 Funny Cars list rolls on, headed soon for the top 10, and although there were no assurances of anyone’s position -- due in no small part to the strength of “the field,” each having earned a berth based on the sheer weight of evidence for inclusion – it’s fair to say that the last few unveilings have ruined many a “perfect bracket” some of you may have been harboring.

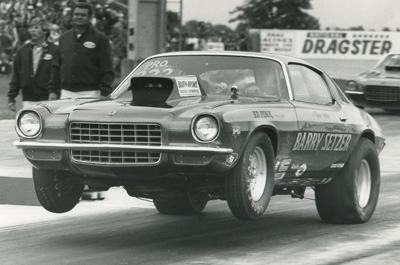

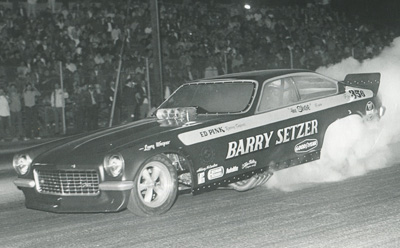

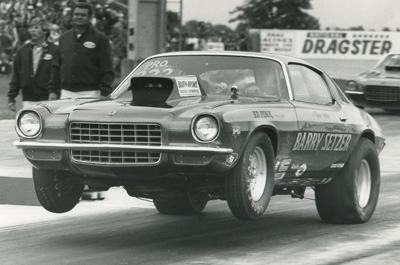

For me, one of the “ouch” moments was when the fabled Pat Foster-driven Barry Setzer Vega was announced in the No. 13 spot. Blame it on the rather nondescript name of the car or its short-lived (two seasons) history, but it was in my personal top 10. As a young fan devouring racing magazines and turning up at SoCal dragstrips as often as I could beg and bargain my parents for a ride in the early 1970s, the Ed Pink-powered Vega seemed nearly indestructible. “Patty Faster” might not always win the race, but he and Setzer almost always left with low e.t., top speed, or both.

For decades, Setzer has been a bit of an enigma for me. I can’t find a single magazine interview that he ever did, and all that most of us know is that he owned a pretty successful textile business in North Carolina and that for a few years he bankrolled a racing team. I’ve written about him several times but always from a third-person, historical perspective.

So, before it’s too late – you know what I mean – I thought it was time to try to unravel the mystery. He wasn’t easy to track down, but eventually, Cole Foster – Pat’s son – was able to get me a cellphone number. Setzer, now in his early 70s, was clearly surprised by my out-of-the-blue call and admitted right away that he had never been one for the limelight.

“The spotlight has always been the place where I’ve been least comfortable, and I always thought I should let the car speak for itself,” he explained of the absence of any previous interviews. “The owner of the great horse Secretariat always said the best spokesman for Secretariat was Secretariat.”

His modesty notwithstanding, Setzer spent an engaging half-hour with me and had very fond and wonderfully clear memories of his brief but highlight-filled time in the sport.

His modesty notwithstanding, Setzer spent an engaging half-hour with me and had very fond and wonderfully clear memories of his brief but highlight-filled time in the sport.

Dispelling any notion that he was just the wallet behind the magnificent machine, Setzer grew up in sport and can vividly remember as a teenager watching Don Garlits race on the old abandoned Air Force strip in Chester, S.C., before turning his trackside viewing into on-track doing, racing a ’55 Chevy and then a big-block Chevy II Super Stocker. He teamed with driver Bruce Walker on a “match race Super Stock” Camaro that became a Pro Stocker, which is how he met Ed Pink. Pink built an all-aluminum engine for the Camaro, which led to introductions to Funny Car drivers and chassis builder John Buttera.

“I decided that I’d like to have a Funny Car, so I had Buttera build me one, and we ran it out of Ed’s shop,” he recalled. “I was just an old country boy who had been in awe of all of the California guys, but once I got to meet them and spend some time with them, I figured out, ‘Why, hell … they’re just guys, too.’ We started sharing thoughts and ideas, and I really enjoyed that part of it.”

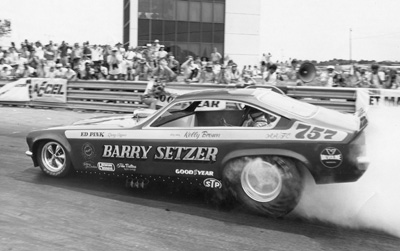

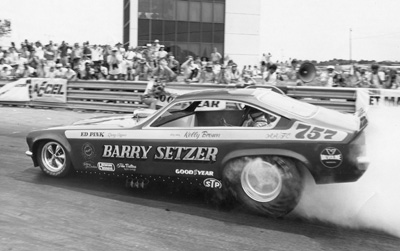

The 28-year-old entrepreneur hired the highly regarded Kelly Brown as his driver, and together they scored a runner-up at the 1971 NHRA Springnationals in Dallas (right). At the time, Foster was driving Don Cook’s Damn Yankee Barracuda, which also had a Pink powerplant, and, as Foster told me in 2008, on a fraction of the budget, it consistently outperformed Setzer’s car, which was the Pink “house car," so to speak.

The 28-year-old entrepreneur hired the highly regarded Kelly Brown as his driver, and together they scored a runner-up at the 1971 NHRA Springnationals in Dallas (right). At the time, Foster was driving Don Cook’s Damn Yankee Barracuda, which also had a Pink powerplant, and, as Foster told me in 2008, on a fraction of the budget, it consistently outperformed Setzer’s car, which was the Pink “house car," so to speak.

“That caught Pink’s attention,” Foster told me. “He asked me to help him with the Setzer car at a test session at Orange County Int'l Raceway. My answer to Ed was, ‘No deal. Put me in the car on a permanent basis, and we’ll talk.’ He did that, and from then till Barry quit drag racing in 1973, we did well.”

“I needed someone in the seat that had a little more clutch experience, and I think Pat was way ahead of his time in that area,” Setzer explained. “He understood how it worked better than anyone. As soon as we put him in the car, it started going quicker and faster. Also at that time, Ed was experimenting with bigger fuel pumps and more magneto voltage, and the notion of experimenting and being creative is also how I became successful in the textile business, so I was all for it. I always was interested in doing something a little different than how everyone else was doing it.”

Setzer was an innovative businessman who funded his racing efforts with a number of successful textile businesses, including Barr Craft Knitting, Barr Hosiery, and Barr Textile Dyeing.

Setzer was an innovative businessman who funded his racing efforts with a number of successful textile businesses, including Barr Craft Knitting, Barr Hosiery, and Barr Textile Dyeing.

Setzer’s textile business at the time – he’d sell and buy back the company several times in different iterations over 20-plus years – was Barr Craft Knitting, which specialized in covered elastic yarn and narrow elastic fabric, the kind that goes into underwear waistbands, bra straps, and lingerie.

“Back in that day, there was a product for the ladies called support pantyhose, and we were the biggest supplier of elastic to Hanes and L’eggs,” he said modestly. “We did all right for ourselves.”

(Although Setzer is no longer involved with his original company, fabric continues to weave its way into his life. He now owns

Victory 8 Gardens, which sells EZ-Gro Gardens, portable raised-bed gardens that use a proprietary, nonwoven propylene fabric called AeroFlow.)

Foster took over the wheel of the candy-red and gold Vega after Indy in 1971 and immediately drove the car to a win at the prestigious Manufacturers Meet at Orange County. How big was the Manufacturers Meet back then? Nearly 70 Funny Cars were on hand, and it took nine hours to complete qualifying to set the four eight-car fields for the Dodge, Plymouth, Ford, and General Motors teams. The Plymouth team, led by Don Prudhomme and Jim Dunn, won the team title, but Foster won the overall driver’s championship — a final run between the cars with the night’s two low e.t.s — when he beat Dunn, 6.72 to 6.77.

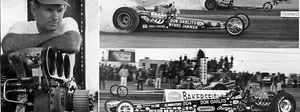

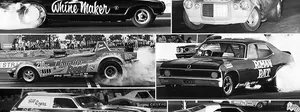

(Picturfed right) Don Schumacher (note 356 car number) got a guest shot in the Setzer Vega at Lions Drag Strip in September 1971. He lost the then-quickest Funny Car race of all time, 6.55 to 6.60 to Gene Snow. (Jere Alhadeff photo)

(Picturfed right) Don Schumacher (note 356 car number) got a guest shot in the Setzer Vega at Lions Drag Strip in September 1971. He lost the then-quickest Funny Car race of all time, 6.55 to 6.60 to Gene Snow. (Jere Alhadeff photo)

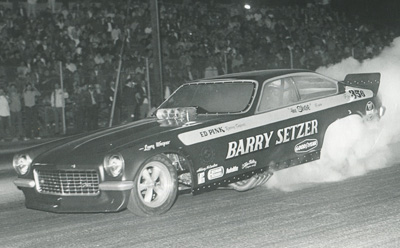

The promise shown in late 1971 revealed itself in full fury in 1972, especially during a five-week stretch in midsummer when they scored a home-state triumph for Setzer at the IHRA Pro-Am in Rockingham, N.C. (where they also set the IHRA national speed record), then won OCIR’s Big Four Manufacturers Championship (with a track record 6.52), triumphed at a smaller weekly show at Irwindale Raceway, and dominated the Hang Ten 500 at OCIR.

As testament to the team, between the Irwindale win and the last OCIR victory, they went to Lions Drag Strip and blew the body to smithereens (Foster even crunched the guardrail), but a week later, they killed ’em at OCIR, qualifying No. 1 and running low e.t. of all four rounds — including a track record 6.47 — and again beating Dunn in the final. They finished the season on a high note at the NHRA Supernationals at Ontario Motor Speedway, carding the sport’s first 6.2-second Funny Car run, a 6.29, in round one. Foster added passes of 6.30 and 6.31 before red-lighting in the final to (who else?) Dunn, who scored his historic first (and only) win with his rear-engine ‘Cuda.

The duo closed their first full season together by setting low e.t. and top speed of the meet at Lions’ Last Drag Race with a 6.36, 229.59-mph effort late in qualifying but were unable to return for eliminations because the chutes ripped off the car on the pass, which sent Foster into the sand trap, damaging the car.

“We went after it seriously on every run, like every run was for the national championship,” said Foster years ago. “We got chided by some of the smaller teams for running that way, but I told them I had a car owner who wanted to tip the world over every time we went to the starting line and that was my job.”

“Of course I always wanted to win,” Setzer confirmed, “but I always loved seeing the car go quick and fast, too.”

The Setzer Vega kicked off 1973 by winning the All-Pro race at OCIR, beating Sush Matsubara in the final (Foster also set top speed at 223.32 mph), and followed with a convincing win at the IHRA Winternationals at Florida’s Lakeland Dragway, where he ran low e.t. in the final to beat Ron O’Donnell. The team then collected its first NHRA score at the Gatornationals, where it set a new national record of 6.36, backed up by a 6.37 in the final round to defeat Don Schumacher. The Setzer machine went on to record two more NHRA runner-up finishes, at that year's Springnationals and Summernationals, to Dave Beebe and Leroy Goldstein, respectively. At the Summernationals, Foster qualified third on a fiery 6.47 pass that left him with burns. He bravely soldiered on and reached the final, where he fell to Goldstein and the Candies & Hughes machine, 6.74 to 6.78.

The Setzer Vega kicked off 1973 by winning the All-Pro race at OCIR, beating Sush Matsubara in the final (Foster also set top speed at 223.32 mph), and followed with a convincing win at the IHRA Winternationals at Florida’s Lakeland Dragway, where he ran low e.t. in the final to beat Ron O’Donnell. The team then collected its first NHRA score at the Gatornationals, where it set a new national record of 6.36, backed up by a 6.37 in the final round to defeat Don Schumacher. The Setzer machine went on to record two more NHRA runner-up finishes, at that year's Springnationals and Summernationals, to Dave Beebe and Leroy Goldstein, respectively. At the Summernationals, Foster qualified third on a fiery 6.47 pass that left him with burns. He bravely soldiered on and reached the final, where he fell to Goldstein and the Candies & Hughes machine, 6.74 to 6.78.

"We did better in match race and IHRA competition," admitted Foster. "The car was good enough to win even more NHRA events, but something always seemed to happen to us in the final."

Foster qualified No. 1 at the IHRA Pro-Am at Rockingham Dragway and was runner-up to Mike Snively in the Mr. Ed Satellite and set low e.t. at the IHRA Springnationals in Bristol. Foster set top speed at the IHRA Northern Nationals and lost in the final to Jim Paoli. Later that year, Foster and Setzer won the IHRA U.S. Open, stopping Dale Emery in the final.

Foster and Setzer parted company at the end of the 1973 season. Setzer had met “a charming young lady” and got married, but before you start thinking it’s “Yoko broke up the Beatles,” Setzer is clear that the decision to quit was his.

“It wasn’t that she didn’t want me to go drag racing,” he explained. “I realized that I couldn’t be the world’s greatest husband, operate a successful business, and be the owner of the world’s fastest Funny Car. The time was right, and I decided to move on. Everyone’s interests follow different courses over time. Some people live their lives doing what they started out doing. I respect and admire those people, but I’m not that way. The creating and the building was always more exciting than the actual doing.”

(Pictured right) Tommy Grove drove a Setzer-branded Vega for a number of seasons after Setzer retired from being an active car owner.

(Pictured right) Tommy Grove drove a Setzer-branded Vega for a number of seasons after Setzer retired from being an active car owner.

Setzer offered to sell the complete operation to Foster, who declined and later very much regretted it. “I didn't want the headaches of being an owner,” Foster admitted. “Don Prudhomme later told me that I had been a fool, and he was right. I had everything that I needed to turn the program into a major sponsorship deal.”

The Setzer name remained visible on a Setzer-branded Vega driven for several seasons by Tommy Grove. Setzer had no real involvement in the car – the arrangement began when Grove garaged his car at Setzer’s shop – but he did work more closely with Lamar Walden on a locally run Pro Stock Vega that carried Setzer’s name in the 1974 and 1975 seasons, a car that Setzer believes could have been a great car if they ever had the chance to sort it out.

Even while he owned the Funny Car, Setzer had his hands in both other Pro classes as well. After Bill Jenkins showed the way in Pro Stock with his small-block Vega, Setzer had Buttera build him another cutting-edge vehicle.

Even while he owned the Funny Car, Setzer had his hands in both other Pro classes as well. After Bill Jenkins showed the way in Pro Stock with his small-block Vega, Setzer had Buttera build him another cutting-edge vehicle.

Recalled Buttera in a 2001 interview with NHRA National Dragster, "One of the problems that they had with the [Pro Stock] Camaro was that it was so difficult to work on. Barry wanted to make the car more accessible, and I said, 'If that's what you want, watch this.' "

The result, according to former NHRA National Dragster writer and Pro Stock historian John Jodauga, was the first "take-apart" Pro Stock car, on which each body panel, with the exception of the roof and rear quarterpanels, could be easily removed with a variety of quick-disconnect devices. The vehicle earned Best Engineered Car honors at the season-opening 1973 Winternationals. “Although it did not knock Jenkins off of the top of the Pro Stock totem pole, its engineering innovations are still very present in today's machines,” wrote Jodauga in a 2001 ND article.

Setzer’s trust in Buttera was so supreme that he even bought Buttera’s wild, monocoque-chassised Top Fueler – an extraordinary machine combining aircraft, aerospace, Indy 500, Can-Am, and Formula 1 technology that I wrote about in a 2010 column that I titled “

The prettiest car to ever run only once,” which goes a long way in summing up the wild ride – after Buttera could not find the financing himself to field the car after a six-month build. The car, as my title implies, only ran once (that we know of), wheelstood, and was retired.

“It was a fabulous car – maybe one of the most beautiful ever – but it never performed quite right,” Setzer told me. “Maybe with a little more effort, we could have done something very different.”

After an aborted attempt to turn it into a rocket-powered exhibition car, the machine was shelved and later donated to the Don Garlits Museum of Drag Racing.

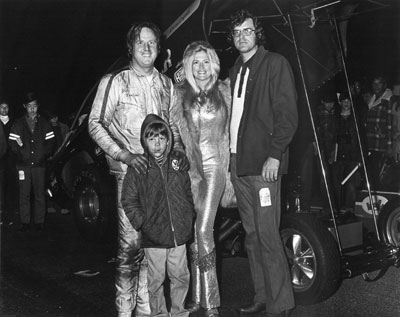

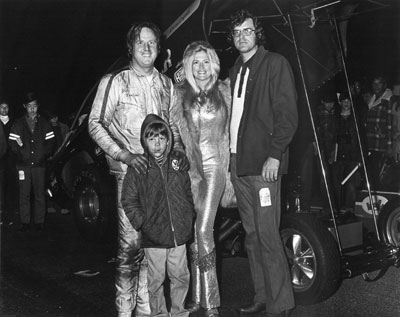

Foster with son Cole, Linda Vaughn, and Setzer in the winner's circle, where they spent a lot of time in the 1972-73 seasons

Foster with son Cole, Linda Vaughn, and Setzer in the winner's circle, where they spent a lot of time in the 1972-73 seasons

As my time with Setzer ran down – he was headed to a business appointment – I made sure that he knew that his name was etched into the memories and record books of many of us and shared some of the platitudes I had gathered.

Not long before his passing in March 2008, Foster said of his longtime friend, “Barry was a quiet, soft-spoken, intelligent man, a man of his word, and always a gentleman. A better car owner would be hard to find. It was a shame that Barry couldn't have kept going in drag racing. There's no doubt in my mind that he would have been a major player for many years, and he certainly would have been in contention for one of the first major corporate sponsorships. Racing with Barry was certainly the highlight of my career. Barry gave me the opportunity to prove my abilities as a driver and engine and clutch tuner.”

In 2001, car builder Buttera called Setzer “one of my favorite, if not the favorite, customers I ever had. That was back in the days when you could try a lot of new things, and Barry encouraged that. Other people were very demanding, but Barry knew how to say please and thank you.”

I asked Setzer to reflect on his short but wonderful time in the sport, and he, typically understatedly, said, “We made a pretty good splash there, didn’t we?

"It was a great time in my life,” he continued. “I enjoyed traveling around the country and meeting people and being exposed to a lot of different ideas and concepts. I tried to make it to as many races as I could and enjoyed it a lot. I enjoyed the people, especially Pat. Pat was like a brother to me. He was a great guy, and the fact that I’ve kept alive a relationship with his son, Cole, I think speaks for itself on how I felt about Pat.

“It is amazing,” he agreed when I told him about the reverence fans like me still have for that car. “I don’t follow the sport much anymore, but I took my car in to get it inspected in a little shop the other day, and the guy told me, ‘I want you to know that you’re still relevant.’ That made me feel good.”

I couldn’t agree more.

His modesty notwithstanding, Setzer spent an engaging half-hour with me and had very fond and wonderfully clear memories of his brief but highlight-filled time in the sport.

His modesty notwithstanding, Setzer spent an engaging half-hour with me and had very fond and wonderfully clear memories of his brief but highlight-filled time in the sport. The 28-year-old entrepreneur hired the highly regarded Kelly Brown as his driver, and together they scored a runner-up at the 1971 NHRA Springnationals in Dallas (right). At the time, Foster was driving Don Cook’s Damn Yankee Barracuda, which also had a Pink powerplant, and, as Foster told me in 2008, on a fraction of the budget, it consistently outperformed Setzer’s car, which was the Pink “house car," so to speak.

The 28-year-old entrepreneur hired the highly regarded Kelly Brown as his driver, and together they scored a runner-up at the 1971 NHRA Springnationals in Dallas (right). At the time, Foster was driving Don Cook’s Damn Yankee Barracuda, which also had a Pink powerplant, and, as Foster told me in 2008, on a fraction of the budget, it consistently outperformed Setzer’s car, which was the Pink “house car," so to speak. Setzer was an innovative businessman who funded his racing efforts with a number of successful textile businesses, including Barr Craft Knitting, Barr Hosiery, and Barr Textile Dyeing.

Setzer was an innovative businessman who funded his racing efforts with a number of successful textile businesses, including Barr Craft Knitting, Barr Hosiery, and Barr Textile Dyeing. (Picturfed right) Don Schumacher (note 356 car number) got a guest shot in the Setzer Vega at Lions Drag Strip in September 1971. He lost the then-quickest Funny Car race of all time, 6.55 to 6.60 to Gene Snow. (Jere Alhadeff photo)

(Picturfed right) Don Schumacher (note 356 car number) got a guest shot in the Setzer Vega at Lions Drag Strip in September 1971. He lost the then-quickest Funny Car race of all time, 6.55 to 6.60 to Gene Snow. (Jere Alhadeff photo)

The Setzer Vega kicked off 1973 by winning the All-Pro race at OCIR, beating Sush Matsubara in the final (Foster also set top speed at 223.32 mph), and followed with a convincing win at the IHRA Winternationals at Florida’s Lakeland Dragway, where he ran low e.t. in the final to beat Ron O’Donnell. The team then collected its first NHRA score at the Gatornationals, where it set a new national record of 6.36, backed up by a 6.37 in the final round to defeat Don Schumacher. The Setzer machine went on to record two more NHRA runner-up finishes, at that year's Springnationals and Summernationals, to Dave Beebe and Leroy Goldstein, respectively. At the Summernationals, Foster qualified third on a fiery 6.47 pass that left him with burns. He bravely soldiered on and reached the final, where he fell to Goldstein and the Candies & Hughes machine, 6.74 to 6.78.

The Setzer Vega kicked off 1973 by winning the All-Pro race at OCIR, beating Sush Matsubara in the final (Foster also set top speed at 223.32 mph), and followed with a convincing win at the IHRA Winternationals at Florida’s Lakeland Dragway, where he ran low e.t. in the final to beat Ron O’Donnell. The team then collected its first NHRA score at the Gatornationals, where it set a new national record of 6.36, backed up by a 6.37 in the final round to defeat Don Schumacher. The Setzer machine went on to record two more NHRA runner-up finishes, at that year's Springnationals and Summernationals, to Dave Beebe and Leroy Goldstein, respectively. At the Summernationals, Foster qualified third on a fiery 6.47 pass that left him with burns. He bravely soldiered on and reached the final, where he fell to Goldstein and the Candies & Hughes machine, 6.74 to 6.78. (Pictured right) Tommy Grove drove a Setzer-branded Vega for a number of seasons after Setzer retired from being an active car owner.

(Pictured right) Tommy Grove drove a Setzer-branded Vega for a number of seasons after Setzer retired from being an active car owner. Even while he owned the Funny Car, Setzer had his hands in both other Pro classes as well. After Bill Jenkins showed the way in Pro Stock with his small-block Vega, Setzer had Buttera build him another cutting-edge vehicle.

Even while he owned the Funny Car, Setzer had his hands in both other Pro classes as well. After Bill Jenkins showed the way in Pro Stock with his small-block Vega, Setzer had Buttera build him another cutting-edge vehicle. Setzer’s trust in Buttera was so supreme that he even bought Buttera’s wild, monocoque-chassised Top Fueler – an extraordinary machine combining aircraft, aerospace, Indy 500, Can-Am, and Formula 1 technology that I wrote about in a 2010 column that I titled “The prettiest car to ever run only once,” which goes a long way in summing up the wild ride – after Buttera could not find the financing himself to field the car after a six-month build. The car, as my title implies, only ran once (that we know of), wheelstood, and was retired.

Setzer’s trust in Buttera was so supreme that he even bought Buttera’s wild, monocoque-chassised Top Fueler – an extraordinary machine combining aircraft, aerospace, Indy 500, Can-Am, and Formula 1 technology that I wrote about in a 2010 column that I titled “The prettiest car to ever run only once,” which goes a long way in summing up the wild ride – after Buttera could not find the financing himself to field the car after a six-month build. The car, as my title implies, only ran once (that we know of), wheelstood, and was retired. Foster with son Cole, Linda Vaughn, and Setzer in the winner's circle, where they spent a lot of time in the 1972-73 seasons

Foster with son Cole, Linda Vaughn, and Setzer in the winner's circle, where they spent a lot of time in the 1972-73 seasons