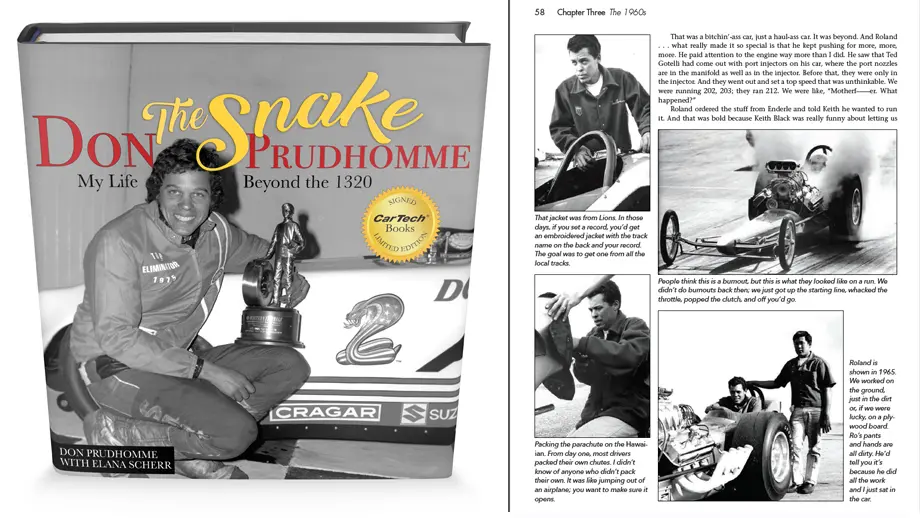

Exclusive book excerpt: Don “the Snake” Prudhomme: My Life Beyond the 1320

My review of the new autobiography, Don “the Snake” Prudhomme: My Life Beyond the 1320, a few weeks ago here stoked a ton of interest. So much so that Prudhomme and his publisher, CarTech, agreed to allow me to share a small chunk of the book with you to give eager members of the Insider Nation (no doubt their target audience) a generous except from one of the chapters.

What's excepted below is part of Chapter 3, which covers the 1960s. It’s fun stuff, with “Snake” talking about the fabled Greer-Black-Prudhomme dragster that made him famous, on getting a knife pulled on him by a fellow racer, on his short-lived drag boat career, his wonderful relationship with Keith Black, and much more. I've included just a few of the photos (less than 20 of the 86 in the chapter) as space allowed. (I've resized a few and used a little PhotoShop magic to move a caption or two, but otherwise they're untouched with his original captions.)

Enjoy!

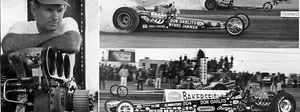

The Greer, Black, and Prudhomme Dragster

When they decided they couldn’t keep running the car, Fuller recommended me to Keith Black. I can’t even tell you what that phone call was like. Imagine if you were a small-time actor and you got a call that a major motion picture wants you for the lead. That’s how exciting this was to me. Keith Black was already a big name. The fact that the timing all worked out so well was just very lucky. I had pretty good luck with most of my career, but this in particular was just a perfectly smooth transition to the new car—and what a car it was.

It was just amazing. Tony Nancy did the interior and the body was Wayne Ewing. When I went to go see it I thought, “Oh my God, I get to drive this.” It was the coolest-looking race car I’d ever seen. I got to paint it, and although it’s recently been restored in yellow, it was originally an orangey-red color like Ivo’s cars. I loved his cars, and Tony Nancy had a highboy roadster that color as well, so we painted the Greer–Black car the same. I probably just had paint left over, but seriously, I did really like the look.

By that point, pretty cars were the thing to have. We were California guys, and all the hot rodding started here. All the hot rodders were painting their cars really bitchin’, and that spread over to the Fuel dragsters too. Once I saw that Greer–Black car with the scoop and that body, it seemed obvious that it deserved a good paint job.

Everyone was fixing up their cars. All the junky stuff kind of came and went in drag racing by that point. The stuff you see in old photos or revival meets where guys just threw an engine in a car and left the gear shift sticking out and it was all flat black or patchwork was out of fashion. That was more the look in the late 1940s and 1950s, but by the early 1960s, paint jobs were important to have on your car. Solid colors, no jitterbug s—— on them yet. We hadn’t got into the flames and stripes; that came later on.

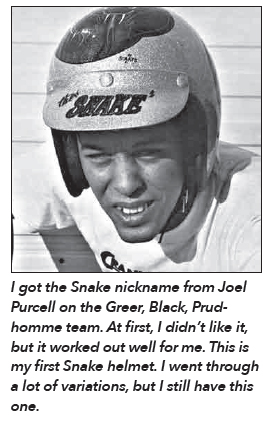

Start of the Snake

One of the important things that happened to me in the Greer, Black, Prudhomme (GBP) car didn’t even have to do with winning a race; it was getting the Snake nickname, which I didn’t even like at first! A guy on the team named Joel Purcell started calling me Snake because of the way I’d leave the starting line. It was sort of a compliment, sort of a jab. I think he mostly meant it as a compliment. He was a funny guy. I was not a funny guy. I didn’t go around cracking jokes.

The nickname caught on, and the announcers and reporters started saying it. That was a real difference in the coverage, when they started writing, “Snake wins at Lions Drag Strip,” instead of Prudhomme. At first I thought, “Oh my God, how can they do that? How would you know who Snake is?” I didn’t realize that I was known more as Snake than I was by my name. I always had trouble with my last name. People couldn’t pronounce it. Even I have a hard time. When I started becoming Snake, it was so easy. And then, Tom McEwen came along and became the Mongoose, and it was Snake and Mongoose. Even today it blows me away. It was so perfect. We were Snake and Mongoose before the Hot Wheels deal. That came later.

Can’t Win ’Em All

We got invited to go to an AHRA race in Green Valley, Texas. I had heard about how tough and fast those Texans were. We did really well there, but when we came up to the final round, we were racing a driver named J. L. Payne. Payne drove for Vance Hunt, and he was a real tough guy. He wore cowboy boots when he drove the race car and was known to carry a knife in those boots.

We raced him in the final round, and he red-lighted against me. I went on down and won the race. Well, he got down to the other end, idled down there, got out, and said, “Let’s do that again.” All these Texans started gathering around us like, “Yeah, that was a foul start, we got to run it again.” So, I said, “Keith, what are we going to do?” They scared the s—— out of me.

Mongoose was there, and he said, “Well, I guess we better run them because we can’t beat them in a fight.” So, we went up there to run them again. On the second run, they kept me hanging out on the starting line for a long time. You know, when you’re in Texas, you do as the Texans do, you don’t make your own rules. They make the rules. I was running low on fuel by the time they pulled into the lights, and when I dumped the clutch the front end went up in the air and I did this gigantic wheelstand. I had to shut it off and bring it back down.

Of course, he went on down no problem and beat me. I pulled in down at the end of the course, and I said, “Okay, you beat us. Now, let’s do it again. You know I did a wheelstand, so let’s do a two out of three.” Payne reached down in his boot and he pulled out his knife. He said, “We ain’t going to do nothing. We won the race, you gone get your ass back to California.” Once we saw that knife, we thought it was best to load our s—— up and head home. That was an experience for a young up-and-coming drag racer. Later, I became great friends with the car owner Vance Hunt. I mean, even back then, I wasn’t pissed. I was scared, but I wasn’t mad. I was blown away by how serious this was to them. I thought racing was everything to me, but I didn’t know that it’d get to the point where a guy would pull a knife on me over a race. Through the years, I’d see Hunt at the reunions and stuff. I’d bring up that thing about him beating us, and he’d get red-faced about Payne pulling that knife out.

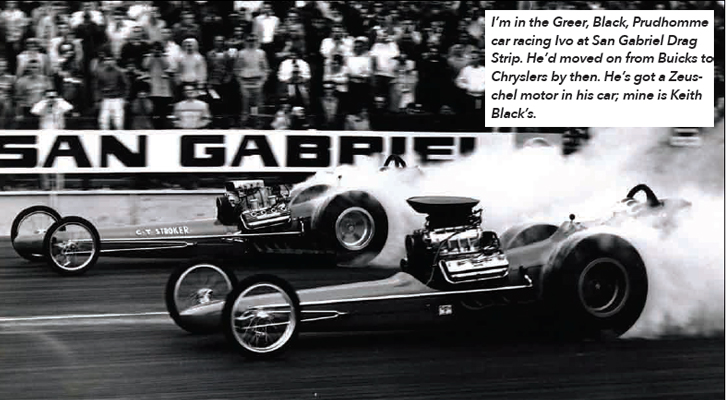

Setting Records with GBP

The GBP car was the most modern dragster of the time. It looks small by today’s standards, but it was the top dog in the early 1960s. It had a 392 Chrysler engine running on nitro and was built and tuned by Keith Black. We won races like everyone else was standing still. I got my first taste of making big news when we set a record by running a 7.77-second pass at San Gabriel. That was a huge deal because until then, no one had even run into the 7s. Well, maybe a 7.90, but having those three numbers in a row, it was like dice or a Vegas slot machine, rolling three sevens in a row, 7-7-7. It was unheard of at the time, but we did it, and everybody knew we did it. It wasn’t one of those hot clock numbers.

All through drag racing (well, in the early days anyway), there were tracks that would kind of juice up their clocks so that the cars would set records because that was good for attendance. People liked to see a fast run or what they thought was a fast run. That’s why there are questions as to if the Greek, Chris Karamesines, ran a 200-mph run first or Don Garlits did. You know Garlits never believed that the Greek did it first, but I think the Greek did. So, let’s just say that many of the clocks were in question around the country.

However, with the GBP car at Irwindale, there was no question. The car just dominated, it was way ahead, and there were a lot of people there to see it. That run, it was all Keith Black. It was one of those cool nights where the air conditions were just great. We used to like to wait until dark, when it got cool out. We didn’t know about air density or anything, all we knew was that the engine liked it when it was cool. Keith had done a lot of work on the car, especially to the clutch to get it to keep performing better and better. It felt good to me on that run, but all I had to go by was the seat of my pants. There were no computers or anything like that in the car. I could tell that it was on one hell of a run, but I couldn’t tell how fast it was until I saw the guys come hauling ass down at the other end in Keith’s Ranchero, blinking the lights on and off. That’s how we knew if we’d done something good because the crew would come hauling in fast, blinking the headlights and honking the horn, and then you knew that you either won, set a record, or were low ET. That was a thrill.

Grown-Up Stuff

The first full year of racing with the GBP car, that was really my first grown-up time period. Lynn and I were married in 1963, and the funny thing is that it cost me a big race! During the NHRA nitro ban, some guys, like Garlits, would run their cars on gas and go race there, but I wasn’t interested in that. For me, it was nitro or nothing. In 1963, the NHRA started running nitro at Pomona again, and Keith wanted to take the GBP car, but there was one big problem. Lynn and I were set to get married on the same weekend that they were going to run the race.

I was just sick about it. Not about getting married but missing that race. Keith, he was all, “Oh, no. Go get married. Do what you’re doing.” He wasn’t like, “Well, can you change the date?” He didn’t think that running the race was more important than my wedding day. They didn’t give me any hassle about that at all. So, I missed the opportunity to run the Nationals then. I think it was worth it.

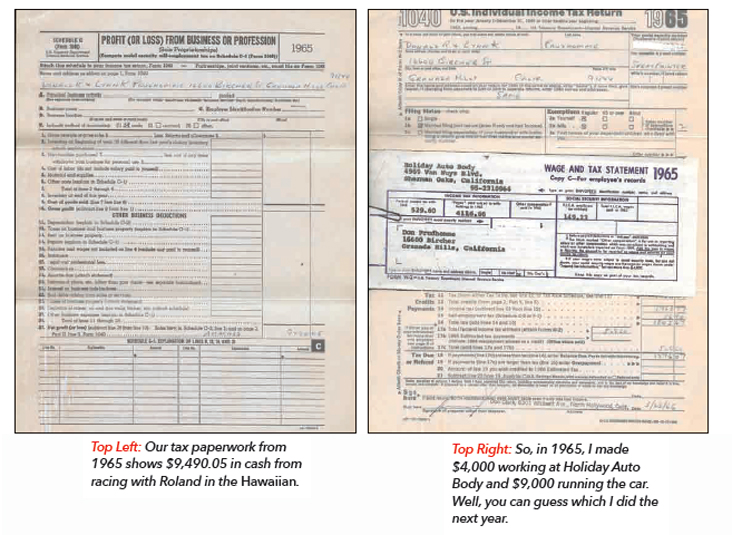

In 1964, Lynn and I bought a house. I couldn’t have even imagined that possibility when I was growing up. I think we paid $26,000. It was a lot of money. We had $5,000 in the bank; it was all from racing, and we used that for a down payment. At the time, I think our apartment payment was a hundred and some bucks a month, and the house payments were almost $200 a month. It was considerably more, and we were like, “God, how are we ever going to do this? How are we going to ever make these payments?” Somehow we did, and it wasn’t a breeze, but we did it and we did it with money from racing, which is pretty wild.

I remember being proud as punch at being able to own a home at that age. From painting cars and not having an education to buying a house in Granada Hills. I stopped by that house some years back, and this guy was working in the yard. I said, “This is really a nice place you got here.” He said, “Thanks. Don Prudhomme used to live here.” I swear to God. I thought it was the funniest thing. It was the coolest thing ever, someone was saying that to me. The guy didn’t even know who I was

A Bad Idea

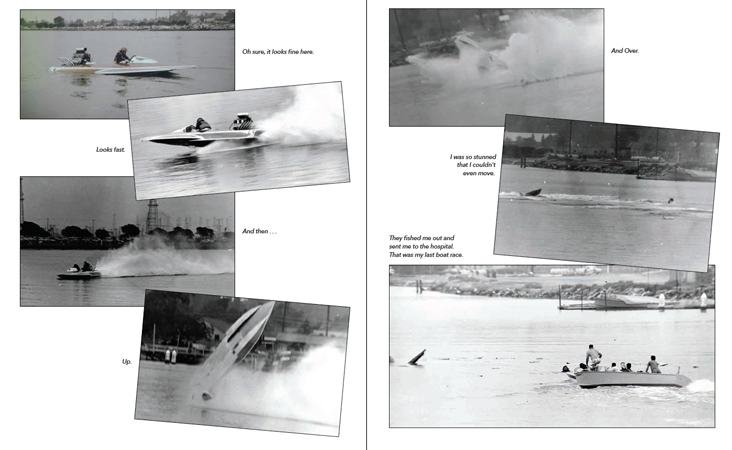

In the fall of 1964, Zeuschel asked me if I wanted to try my hand at boat racing. He built racing engines for boats too, really fast boats. He was building an engine for a guy named Rene Andre, and they asked me to drive it. It was a blown gas hydro with a wooden hull—not fiberglass. It was before fiberglass. It was built by Hallett. I said, “S——, why not.”

Well, I soon found out the reason why not. That was a real short experience. I drove it a couple times, then crashed it at Marine Stadium in Long Beach. Mickey Thompson pulled me out of the water. He was racing a boat too. I came up out of the water, and I was floating there thinking, “God, I’m still alive.” And my helmet, I remember my helmet floating next to me. Motherf——er. I mean, it ripped my helmet off. It felt like it ripped every bone and muscle in my body. I had a life jacket on, thank God, because I wouldn’t have been able to fight to stay up on top of the water. I was just floating there until the rescue boat came.

It was one of those times where the lights went out and I was sure I was dead. I mean that’s how it feels. Then all of the sudden, the lights come back on, and you go, “Oh. Blue sky. Thank God. Whatever’s wrong with me I can fix. I’m alive.” They pulled me out of the water and put me on a stretcher. Mickey Thompson came running over, “You gonna be all right? Gonna be all right till I get you to the hospital?” And he took his wallet out and sort of shoved it into my armpit and said, “Here. There’s plenty of money in there. Whatever you need.” He didn’t know if I had any money or anything. I think that fortunately, I didn’t need it. All I needed to do was get some rest because it didn’t break anything; it just tore muscles and everything hurt. Just f——ed me up for a while.

Keith was really pissed at me. That was one of the few times we had a falling out. He thought that I shouldn’t have put my life in danger driving for his competition, driving for another engine builder. It wasn’t the smartest thing for me to do at all. I mean, it was stupid, actually. But when you’re young, you’ll just jump in anything. And it was a huge mistake. Rene ended up driving it himself after that and flipped it again. When the boat came down, it hit him in the shoulder, and he had a dead arm from then on. He was paralyzed on one side. I think he had to have it amputated later on. That could have been me. I didn’t go around boats after that. I didn’t want anything to do with them.

The Hawaiian

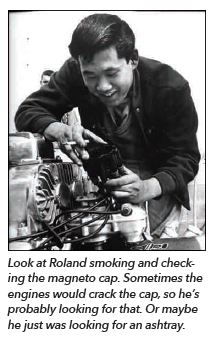

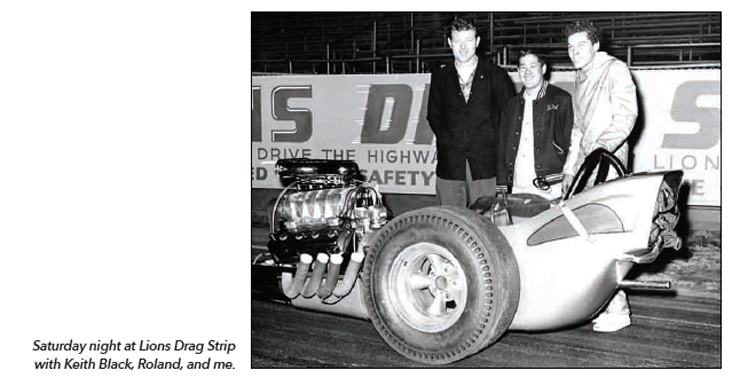

Another example of how some points in my life seemed to transition perfectly (through nothing that I did or at least nothing that I knew I did) was my luck in meeting Roland Leong. It was in Hawaii in 1963. Roland had a dragster with a Keith Black engine. Keith built the engines in Los Angeles and shipped them over there.

There was a guy there, Jimmy Pflueger, who owned a dealership on one of the islands. He had just opened a drag strip, so he wanted to promote it. He said, “How can we get Keith Black and the dragster over here?” They worked out a deal. I wasn’t involved in the finances, but somehow they shipped the dragster to Hawaii. Then, they flew me and Lynn over too. It was a long flight, and a big deal, and I didn’t give a s—— about going to Hawaii. All I cared about was getting out to the drag strip.

Roland picked me up and showed me around. We went to dinner with his mom and his family. He was younger than me, maybe 18 years old. The next day, he took me out with him, and we hung out all day. We went to Jimmy Pflueger’s car dealership, I got to meet his buddies, and it was a good vibe. A lot of them thought that I was Hawaiian. It wasn’t unusual to have different skin tones there. They all asked Roland, “Is he your brother? Hey brother. Hey brother.” That’s what they called another Hawaiian. I liked that part, but again, I really only ever thought about racing.

There I was in Hawaii, and I didn’t learn to surf or anything, but Roland was like that too. We were total gearheads. All we talked about was drag racing. We’d go over to a buddy’s house or something and other people talked about music, girls, or food, but we were just ate up with drag races and drag cars.

Speaking of food, I was pretty unsophisticated, so I didn’t have any experience with the kind of food that they eat in Hawaii: raw fish and sushi. Now I love it. I remember we went to the car dealership, and they had a food truck (they call it a roach coach there). I looked inside and had no idea what to do with the options. Roland said, “Come on, Vipe [he called me Vipe for Viper]. I’ll show you this.” We ate some rice balls rolled up with fish and eel. He had to show me how to eat it, and he got a kick out of that.

I was over there about a week, racing and seeing the island. Roland came to the mainland right after that, which was great because I didn’t know if I’d ever see him again after we left Hawaii. Then, he showed up at Keith Black’s back in Los Angeles. He came walking in, “Hey man, what’s up? I’m over here. I’m building a car.” He’d built a car just like the Greer–Black car. When I look at our friendship now (and we are still so close to this day), I wonder if some of what connected us was that he was unusual in the scene, being Asian. Roland looked different, and I looked different, and we both kind of bonded over that a little bit. He doesn’t talk about it much, but a lot of people were prejudiced against the Japanese and Chinese. There were things happening in Vietnam, and people in Los Angeles didn’t really distinguish where someone was from, they just knew they were Asian. I remember when he looked for an apartment, he wanted to move where there were other Asian families, which I didn’t understand at the time, but I do now. Between that and the shared car interests, we were strongly connected. He was like a little brother to me.

What ended up happening is that he built a dragster, and we took it to Lions Drag Strip for his first runs. I buckled Roland in. I didn’t know that he couldn’t drive the thing! He’d been racing a dragster in Hawaii but not a nitro car. I had such good luck with the cars I’d been driving that I thought everybody could do it. He got in it and took off going down the track, but all of the sudden, the car goes right off the track.

There was a berm on the side at Lions. He got off the track and went up over the railroad tracks. He ended up right up on the train tracks, f——ed the car all up. I rushed down there and was the first one to him. He looked up at me and said, “Vipe, what happened?” I said, “I don’t know. You tell me.” I wasn’t laughing. I was scared for him. I thought he was hurt. He didn’t know what happened. Nothing, he just crashed the f——ing thing.

When we got back to the shop. Keith called him into the office and said, “Hey, I’ll build your cars for you, but I don’t want you to drive.” He didn’t want someone to get killed in his car, but also, and I didn’t know this yet, he and Greer were talking about hanging up the Greer-Black car. Greer was running out of money, or at least he wanted to spend it in smarter places. Keith told Roland, “You should get Don to drive it.” Roland asked me to drive it, and I said, “Hell yeah, I’ll drive it. You bet.” And that’s how I ended up working for Roland on the Hawaiian.

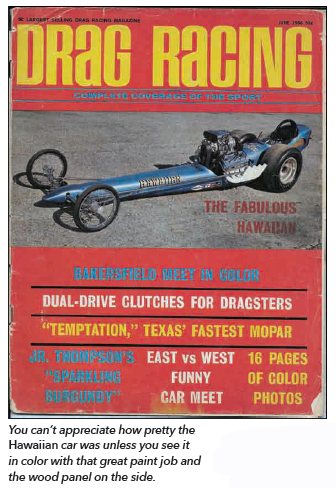

That was a bitchin’-ass car, just a haul-ass car. It was beyond. And Roland . . . what really made it so special is that he kept pushing for more, more, more. He paid attention to the engine way more than I did. He saw that Ted Gotelli had come out with port injectors on his car, where the port nozzles are in the manifold as well as in the injector. Before that, they were only in the injector. And they went out and set a top speed that was unthinkable. We were running 202, 203; they ran 212. We were like, “Motherf——er. What happened?”

Roland ordered the stuff from Enderle and told Keith he wanted to run it. And that was bold because Keith Black was really funny about letting us tell him what parts to put on it. But when we put them on there, the car immediately ran faster and quicker. Really, everything with the Hawaiian was good right from the start. I mean, we won the Pomona Winternationals right off the bat and several other local races at Lions and up and down the West Coast. That summer we went on tour.

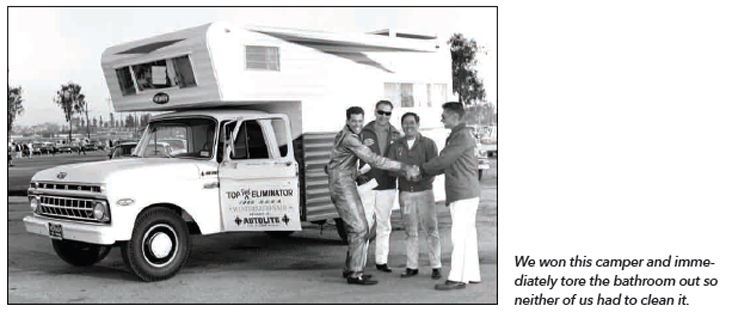

Noah’s Ark

We won a Ford truck and camper in Pomona, and we decided to use it as our tow rig. The first thing we did was tear the bathroom out of it because it wasn’t like either of us was going to clean it. What we should have done was put a bigger fuel tank in it. It had a little bitty tank. The thing got like 5 miles to the gallon or something. It was also a huge pain to turn it around on those small tracks.

Back then, we still push-started the cars, and a lot of time there wasn’t much room to maneuver. We needed a way to haul the car, and now we were big shots, so we weren’t going to use a little open lollipop trailer like back in the Ivo days. I had a neighbor who did woodworking as a hobby. We didn’t know anything about building an enclosed trailer because nobody had them. He built it in my driveway, and the whole thing was wood. It was so f——ing heavy. It was like Noah’s ark. If the thing ever went in the water it would float, but we towed it all around the country. The camper and this huge overloaded trailer was an evil combination on the road and at the tracks.

By the time we got to Chicago, Roland sold the Ford and bought this bitchin’ Dodge station wagon with wood paneling on it. It looked great. The Hawaiian, it fit the image. The dragster had a little strip of the same wood on the side with “The Hawaiian” written on it, where the vents were, back by the parachutes. It was very tastefully done. All of Roland’s stuff was really nice. He did the design and everything, and it looked great.

On the Road Again in 1965

It was a totally different experience being on the road with Roland than it was with Ivo. Roland and I were more alike. We ate and cared about the same stuff. We talked about the car constantly. What does it need? How can we make it go faster? What do you think of this? What do you think of that? We pretty well had it figured out by the time we got to where we were going. We had this crazy schedule: racing, driving all night to the next track, and popping pills to stay awake. The idea was that one guy was supposed to stay awake while the other guy gets some rest, but with us, I’d pop a pill, and then Roland would pop a pill to talk to me to keep me awake. So that means we’re both going down the road chewing our tongues. But that’s what we did to get around, just the two of us.

“The Reverend Mr. Black”

We’d talk a lot about Keith. Black said this or that. This trip, being on the road without Keith Black, that was a big deal for us. A lot of people thought we’d never make it work without him, and they weren’t wrong to think that. We had almost no experience running the car all on our own. We’d get to a track or a hotel and call Keith, tell him what we knew about the track, and he’d tell us what to do. Roland and I were really tight with Keith, but it wasn’t like the way we were friends with each other. We were kids. Keith was a proper grown-up; he had a shop and business plan. He wasn’t what you’d call “one of the guys.”

Ed Pink, a rival engine builder, would stay late, shoot dice, and gamble with all the boys, but that would be the furthest thing from Keith’s mind. I don’t remember him doing anything like that. His dad was a preacher, and so we used to call Keith “The Reverend Mr. Black.” He was a real clean-cut guy. He didn’t like our off-colored jokes. He wasn’t that kind of hot rodder. We were pretty wild, and he used to kind of get on us about that. We thought he was kind of square.

The book costs $49 and will be widely available in bookstores and online and should ship within the next week or so, but, if you buy it directly from Prudhomme (www.snakeracinggear.com), he'll autograph your copy at no extra charge.

Phil Burgess can be reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE