Al Segrini

By their very nature, lists are polarizing. Whether it’s the top 10, 20, 50, or 100 anything that you’re trying to establish, there are going to be hits and misses among the critics and delight and disappointment among those who made or didn’t make the list.

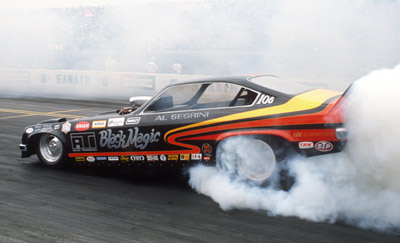

Al Segrini, a five-time NHRA national event Funny Car winner and three-time top-10 finisher, does not hide the disappointment of not seeing any of his Funny Cars – most notably the beautiful Black Magic Vega and any of his Faberge-sponsored Super Brut machines -- on the top-20 list released a few weeks ago, and we chatted about it earlier this week in an hour-plus phone conversation that only increased my appreciation for his career behind the wheel.

Segrini, recognized last year as grand marshal of the NHRA Motorsports Museum New England Hot Rod Reunion presented by AAA Insurance at New England Dragway for his accomplishments and his continuing fan support in the region, works these days as a project manager for a company that builds high-end homes, but for more than two decades, his home was behind the wheel of a Funny Car.

The Massachusetts native got his first flopper ride in the injected-nitro American Express Camaro fielded with his brother, Lou, in 1971. That car was preceded by a good-running B/Gas ’55 Chevy and an injected-fuel altered. Segrini had driven the Chevy, but his protective older brother thought the altered was too much car for his young sibling, so he initially hired Joe Fleming to drive it. After enough pestering, Segrini was allowed to drive the car and proved a natural, guiding the sometimes ill-handling ’23-T to strong performances and victories. Fleming got back into the cockpit one afternoon at New England Dragway and ended up crashing heavily and destroying the car. “We pretty much brought it home in a basket,” recalled a “peeved” Segrini.

Paul Wasilewski Jr.

Lou ordered the American Express car to be built and insisted that the chassis builder, Pete Tropiano, locate the cockpit off-center, toward the “driver’s side,” in a fashion similar to that of the successful Chi-Town Hustler. They took the injected-fuel 427 Chevy right out of the altered and joined Tom “Smoker” Smith’s circuit, running in the Southeast. The car was a winner from the start, and Segrini loved driving it. Compared to the altered, “it was like driving a limousine,” he recalled.

The brothers racked up a series of wins against their mostly Hemi-powered opponents but finally had enough of what they considered to be a constantly shifting set of rules and returned to New England Dragway, where track promoter Jack Doyle had a soft spot for them.

"All of the AA cars would run there — [Don] Schumacher, [Gene] Snow, [Don] Prudhomme, [Tom] McEwen – but Jack told us we could park off to the side, and if one of the AA cars breaks, we could jump in as an alternate. Lo and behold, it seems like we’d get into every show because those guys would do a burnout and break, so they’d push them off, we’d fire off, and I’d run against some AA car, and we did pretty good, too. After a while, some of those guys got pretty pissed off because our car always went down the track. One of them – I think it was Lew Arrington – refused to run against me. ‘That kid is going to make an ass out of me,’ he told Jack. ‘That car hauls ass straight down the track; I’ll look like a fool,’ but they told him to race me or go home. I think we ended up in three or four finals. We never won, but we gave them a race.”

The brothers hung out with the big guns and even ended up crewing for “Jungle Jim” Liberman on occasion. “I’d open oil cans, clean the oil pan, whatever he needed, and he’d let me sit in the car and steer it coming down the return road,” he remembered. “What a thrill; he was my hero.”

Familial obligations forced brother Lou to retire from racing in 1972, but Al’s reputation was already such that when fellow Massachusetts Funny Car driver Kosty Ivanoff got in a nasty crash at New England Dragway, he hired him to drive his supercharged Boston Shaker Vega while he recovered in 1973. It was during the 1973 season and regular racing trips to the Maryland area that Segrini met Jim Beattie, who owned ATI, a top name in automatic racing transmissions. Beattie, a big Funny Car fan, ultimately decided he wanted one of his own and put Segrini in charge of the project.

A Woody Gilmore car was ordered, and Segrini wisely chose Kenny Youngblood to dream up a paint scheme for the car, which was to be named Black Magic. Youngblood responded with one of his all-time great designs, a flowing trio of stripes – orange, red, and yellow – on a brilliant black background. Famed SoCal painter Tom Stratton applied the colors, and ‘Blood insisted on doing the lettering and airbrush work himself. The car also featured extensive chrome and polish and revolutionary faux-marble anodizing. “Oh my god,” Segrini still marvels today. “That car was beautiful.”

The car was named Best Appearing Car in its debut at the 1974 Gatornationals, where the team also collected Best Appearing Crew honors, an unprecedented feat in those times.

“Back then, it was the Dark Ages; everyone wore greasy T-shirts and shorts, but Jim and I designed uniform crew shirts, and everyone wore matching black Levi's,” he said. “Someone told me later that when we pulled up for our first qualifying run that the [NHRA officials] in the tower went to the glass to see it and that [NHRA founder] Wally Parks pointed to it and said, ‘That’s the future of drag racing there, guys.’ Before long, everyone had uniform shirts.”

Segrini drove the Black Magic for three years, but the biggest highlight came early, in the 1974 season, when they reached the final round of the Summernationals and pulled in to face none other than Liberman, who also was appearing in his first national event final round.

“Unbelievable,” mused Segrini. “I go from a kid hanging on the fences watching those AA cars run to racing my hero in the final round.”

“I could see his front tires up in the air out my window,” Segrini recalled. “I wouldn’t lift, and he wouldn’t lift. I was smoking the tires trying to keep it straight, and he was in this big ol’ wheelie that I couldn’t believe. We ended up beating him, and I remember seeing him on the return road with his head down. It was emotional for me because he was my hero, but he told me, ‘Good job, kid,’ but he won [the Summernationals] the next year, so I was happy to see that.”

Beattie brought a second car – the Black Stang, driven by Pee Wee Wallace – into the fold, but Segrini had misgivings about the way that Beattie had the car built. Offered a chance to drive the ill-handling car at a match race, Segrini refused. “First, I didn’t want to embarrass Pee Wee, and, second, that car was evil,” he said. “And that was the beginning of the end for me and Jim.”

In 1978, he began driving for Fred Castronovo and the Custom Body Enterprises team, in a beautiful H&H-built Arrow. “Driving that car was like owning a Rolex watch,” he marveled. “Everything fit perfect – the levers, the tinwork, the way the body clicked into place.” The pretty car was destroyed in a crazy crash at the 1979 Summernationals due to an ongoing problem with exhaust-valve heads that would break off and punch a hole in the piston, leading to a dieseling problem when the engine would not shut off.

The problem came to a head on its opening qualifying run. Segrini got the car stopped just past the lights, but the engine wouldn’t shut off. Oil coming out of the headers from the holed piston caught fire and set the entire car alight. Segrini finally had to bail out of the cockpit, and the car took off, idling down through the shutdown area before crashing headlong into the retaining rail at the top end. “The car pretty much committed suicide,” said Segrini.

The team rebuilt, but the entire operation was stolen overnight while parked outside the home of a friend in New Jersey in preparation for running in Englishtown the next day. The truck and Chaparral trailer were found at a nearby shipping dock, but everything inside the trailer – the car, every part, and even the cabinets – was gone and never seen again.

Once again rideless, Segrini got a lead on a high-ranking contact at cosmetics maker Faberge from a mechanic friend. “He was just a greasy old mechanic at a greasy old shop, but he told me that this kid who used to clean toilets for him at his gas station now was a big wheel at Faberge,” Segrini recalls. “I was pretty sure he was full of [baloney], but he picks up the phone and calls the guy and gets me a meeting with the head of sales, Steve Hainsworth. I bring a rendering to the meeting of what a car could look like, and tells me he’s going to show it to Craig Barrie, who was in charge of marketing. Craig’s father, George, was CEO, and his brother, Richard, was the president.”

Segrini traveled to New York – his first trip into the Big Apple – and to the massive Burlington House skyscraper on Avenue of the Americas, where Faberge, then the top fragrance maker in the country with spokespersons such as Joe Namath and Farrah Fawcett, occupied two full floors of Andy Warhol-decorated offices. Craig Barrie, as it turns out, is not some stodgy executive but a young guy with long hair and gold chains who is a big fan of racing. He’s all for the idea and carries it up the chain of command. Segrini’s asking price is $125,000, not a small sum then. After several meetings over many weeks, a deal is struck, but the contract is for just $100,000. But as Segrini is walking out after signing the 40-page, legalese-filled contract, Craig walks up to him and hands him an envelope. Inside is $25,000.

“I didn’t even own a spark plug at the time, so I had to get going pretty quick,” he said. “Fortunately for me, Tom Prock and Pancho Rendon had just split up, and Pancho leased me their old car [the Gratiot Auto Supply Arrow], motors, parts, and a trailer. I took it to [Bob] Gerdes [at Circus Custom Paint], who painted it that dark green. We debuted it at Gainesville [in 1980], where Faberge guests on hand were impressed that the fans knew who they were.”

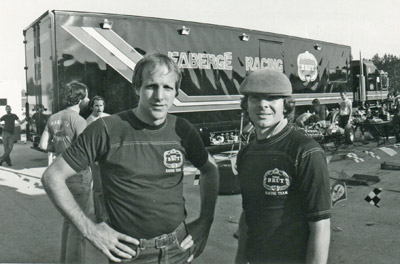

Segrini, left, Craig Barrie, and their beautiful Faberge 18-wheeler

After a successful 1980, in which Segrini also appeared at regional sales meetings, the deal was renewed for 1981, with Barrie, who also liked to work on the car, leading the way. This contract was worth $225,000. Barrie also took note of the 18-wheelers that were becoming more popular and decided that what was essentially a traveling billboard for about the cost of a billboard in Times Square was a good investment and commissioned Segrini to get them one.

Segrini and Faberge finally enjoyed the sweet smell of national event success at the 1982 Winternationals with the Super Brut Omni, winning a final-round battle of the fragrances against Raymond Beadle’s English Leather-backed Blue Max. It was the first of three Winternationals wins in four years for Segrini, two of which ended in spectacular fashion.

Segrini went to two more finals in 1982 – losing to Frank Hawley in both, at the Springnationals and Cajun Nationals, and finishing a career-high sixth in points -- but, surprisingly, did not qualify for the 1983 Winternationals yet went on to win the Cajun Nationals later that year with his new Trans Am after Steve Plueger worked on the chassis. He again finished sixth in points.

Segrini chalked up his third win and second in Pomona when he beat Tim Grose in a memorable final round in 1984. The camshaft snapped right in the lights, leading to a massive blower explosion that blew out the windshield and damaged the body. The win was bittersweet for Segrini.

“At breakfast that morning, I had been told that the Faberge deal was over,” he said. “There had been a corporate takeover, and George Barrie only had 49 percent of the stock. Talk about a high and low all on the same day. We finished the year with Faberge on the car, but the deal was over.”

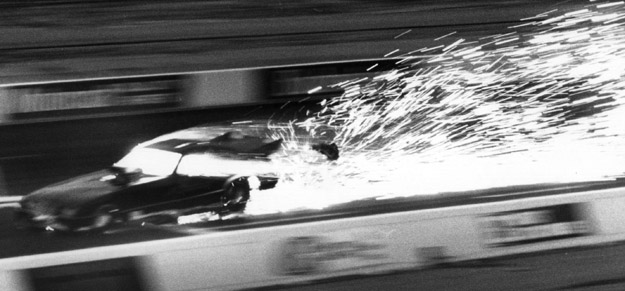

Segrini’s reputation as a solid driver earned him a chance to win the Winternationals again the next year. Joe Pisano had just finished development of his new engine block, the JP-1, and asked Segrini, who was like family and usually stayed at the house of “Papa Joe” on his West Coast trips, to drive his new Daytona. They won the race, and again Segrini was spectacular in victory. You know the old saying, “If you can’t win at least be spectacular”? Segrini did both for the second straight year as the clutch let go in the lights, sending a shower of sparks out of both side windows as he crossed the finish line ahead of Dale Pulde.

“He was running just a three-disc clutch at the time, so we were feeding it parts after every round,” recalled Segrini. “As we went to push the car away from the trailer for the final, it wouldn’t roll backwards, just forward. I knew something was wrong, but I knew I had to give it a shot. After the burnout, it wouldn’t go into reverse. It was vibrating real bad. I held the brake and whacked the throttle and went into reverse and had to do the same thing to get it back out of reverse. The car went about two car lengths before the clutch welded itself, and it was like a lockup clutch before we had those. It opened four car lengths on Pulde. About 1,000 feet, it was shaking and rattling, and just as I lifted, [the clutch] came apart. The sparks were from the titanium can, which held up fine, but I couldn’t see anything, and I had my left leg tucked back as far as I could and my right foot in the top hook of the throttle just in case it came apart. It was spectacular, but we won.”

Segrini drove a few more races for Pisano that year with no real success, and despite his best efforts, Segrini was not able to put together another ride. It wasn’t until the early 1990s that he resurfaced, this time in the dragster of former Top Fuel racer Billy Lynch. The Swindahl-built car had the best of everything, except luck, and after two seasons, they parted company.

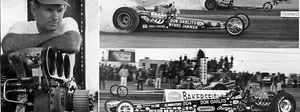

Segrini, right, with longtime friend and nitro racer Paul Smith at last year's NHRA New England Nationals. In 1974, Smith finished second in the world championship race; Segrini was sixth in the Black Magic car.

Segrini’s last ride was for his old pal Plueger, in Sonoma in 1997. His sharp driving got them into the Funny Car field, but they lost in round one. Almost 20 years later, he still maintains a presence in the sport. In addition to serving as the grand marshal at last year’s New England Hot Rod Reunion, Segrini took part this year in a panel discussion at the Winternationals, and he helps his buddy Mike Hard, who has the Hard Guys Nostalgia Funny Car that Mike Smith drives.

“I had some good moments in my career, and I think I brought a lot of stuff to the sport, like the uniforms and the sponsorship of a major company like Faberge,” he reflected. “When I look back at the Top 50 [Drivers] list [from 2000], I think I could have been on that list, too. Me and Dale Pulde -- who I think is one of the greatest drivers ever -- both. I was glad to see Dale had a car in that [Funny Car] top 20 because he deserves it, and it kind of hurts my feelings that none of my cars were. I think I did a pretty good job of representing NHRA, and some of the stuff I did, I feel like I was way ahead of my time, but I know it’s not personal, just puzzling.”

As I said in opening this column, lists are a tricky thing. There are probably 50 cars for which I could make an argument for inclusion on that top-20 list, and even though 20 was all I got, it’s hearing stories like Segrini’s that make me want to make it a top-100 list.