Get on board!

Not many of us are ever going to know what it feels like to be inside a Top Fueler blasting down the track or fight the wheel of a Funny Car as it bucks its way down the track. The proliferation of onboard video cameras in all forms of motorsports has given all of us a bit of a glimpse into how that world looks, but long before that ever happened, drag racing photographers were finding ways to do the same with their still cameras.

These types of photos have always intrigued me, and I had the chance to work with the late, great Leslie Lovett on many of his later experiments with techniques and to understand how some of the earlier ones were taken, and I’ve gathered a collection of them below to share.

(The ol’ broken leg — getting better every day, thanks for asking — has kept me mostly deskbound and out of the actual photo library that houses what surely must be millions of photographs taken by National Dragster staff members or submitted for publication in our fair magazine over the last 53-plus years. Although I’ve learned to balance and/or hop on one foot with a skill level that would surely embarrass any six-year-old playground hopscotch hotshot, it’s just not a comfortable way to go through file drawer after file drawer looking for what I need — especially when I’m sometimes just on a fishing episode and not really sure what I’m looking for. Fortunately for all of us, we have, over the last dozen or so years, scanned and filed a lot of images — looks like about three terabytes of stuff dating back to the 1950s — that are available for browsing on a file server, so I’ve been spending a lot of time combing through all of the folders and subfolders that hold a good portion of our sport’s history.)

Today, it seems like everyone and their brother has a Go-Pro camera mounted to their snowboard helmet or motorcycle, so that type of “first-person” photography has become expected, but it definitely was new and fresh in the 1960s when the dragstrip photogs started laying around.

Early on in the game, you had two choices after you mounted the camera: set it on a timer to open the shutter after a pre-set delay or give the driver a way to do it remotely. The advent of auto winders and/or motordrives made the process a whole lot easier because once the button was pushed to take the first image, it would continue firing until the roll of film was exhausted.

The trick then became one of math: If you motordrive fired at three frames per second and you have a typical 36-shot roll of film, you had enough for 12 seconds, plenty enough for a nitro car or Pro Stocker. Leslie would have the camera set up, flip the switch as the driver was staging, and that was it. By the time the car had the chute out, the roll was filled.

When the drives began reaching five frames per second, the window obviously became a lot narrower, and I remember him using various remote controlled sensors to begin the sequence once the Tree turned green, for example. Today, motordrives are capable of 12-14 frames a second, but with digital cameras, putting the images onto a disc, you’re not facing the same issue of limited number of frames.

Let’s take a look at some great examples of this type of early work.

|

|

In my mind, this is one of the most famous of the bunch because it was the front page image after Bennie “the Wizard” Osborn won his second straight NHRA Top Fuel championship with his second consecutive win at the World Finals at Tulsa International Raceway.

Lovett captured the whole run, from tire-smoking leave to parachute out, using 34 frames. The front cover image was chosen because you can see the distinctive Tulsa tower behind the cockpit. As you can see in the proof sheet of negatives at right (you’ll have to enlarge it by clicking on the link), he fired off three or four test images (you can see the push truck behind the car) and then set it loose just as the car was leaving the line. (The images begin at the bottom of each strip of film)

It looks like the actual photo used was about the third pic; other images have some blur, perhaps from tire or chassis vibration or wind — obviously, he had to mount the camera on the framerail well in front of the engine. You’ll notice that by the end of the run, the frame has shifted slightly because you can see more of the blower pulleys at the end of the run than you can in the beginning. You can see the exact instant he took his foot off the loud pedal as the injectors closed, followed two frames later by the first hint of the parachute deploying, then blossoming. I picked one of the car chutes out to accompany the launch photo.

What really strikes me about these images is that Osborn — and every racer who let Lovett put a camera on their car — trusted him implicitly that the thing wasn’t going to fall off mid-run and clock them in the head or fall beneath the tires. Leslie had that way about him; everyone loved him, and everyone trusted him.

| A few years later, Lovett duplicated the Osborn experiment with recent Insider feature subject Herm Petersen, doing an end-of-end sequence at the U.S. Nationals in, what I think is, 1972. It’s also quite a dramatic series of pics that show him blasting through the traps. I don’t have immediate access to the whole sequence, but I remember in one of the last ones, it almost looks like his hands are crossed on the wheel as he fights to keep the car straight. This image is still plenty nice, showing the old Hurst crossover bridge and tower; unmistakably Indy. Update: Just heard from Herm, who explains that his hands appeared crossed because he used to use his right hand to pull the chute-release level, which was on the left side of the cockpit. This car, by the way, was the first rear-engined car in the Northwest and the car in which he won the big PDA event at Orange County Int'l Raceway in 1972, beating hitters like Don Garlits and Tom McEwen en route. |

|

|

|

|

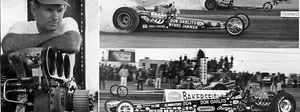

I’m not sure who gets credit for the next trio of images, but I love them, too. Above is obviously “Big Daddy” Don Garlits melting the hides on a pass in what is either 1964 or 1965 (his 1964 U.S. Drag Team decal is visible on the cowl). The camera must have been mounted on the cowl, just behind the blower. The image at left reminds me of the Osborn pics, though it’s a little more in-your-face to the injector. I’m not sure who this is — some people think it's also Garlits — but it kinda looks like Carlsbad Raceway. I’m not really sure who is responsible for the image below, but it was taken from the vantage point of the cockpit of Darrell Gwynn’s Alcohol Dragster during Florida’s winter series event. The Tree is kind of blurred on the right, but you can see Gwynn’s hand still on the handbrake, which must mean he just launched. |

|

|

|

There’s a lot going on in this photo of Bruce Allen at the wheel of the Reher-Morrison Pro Stocker at Indy in 1986. I’m pretty sure that this was taken during the Mr. Gasket Pro Stock Challenge bonus race. Lovett mounted a camera in the “passenger seat” and began firing as soon as Allen took the green. You can see by his hand on the Lenco shift lever that he’s already a bit down track, either just having pulled third or preparing to do so.

|

Lovett mounted a camera on the “dashboard” of Ed McCulloch’s Miller American Olds Funny Car at the 1988 U.S. Nationals to get this great shot of “the Ace” during his burnout, You can see him correcting the wheel to the left and smoke filling the cockpit, highlighted by the sun streaming through the side window.

|

Here’s another image that ran on the cover of National Dragster, taken in mid-burnout from the vantage point high on the wing of Gary Ormsby’s Castrol GTX Top Fueler. Obviously, wings are tricky business, and the camera didn’t make the full pass — we certainly didn’t want to cause a wing-strut failure or something crazy — but it is a neat birds-eye lens. The race was rain-delayed a week, so we were able to use this on the cover of the rainout edition; unless Ormsby had won the race, we certainly wouldn’t have thought of putting it on the cover otherwise.

I know there are a lot more pics like these out there, so send them my way; I’d love to show them off.